The Times Shreveport, Louisiana Saturday, September 02, 1972 - Page 9

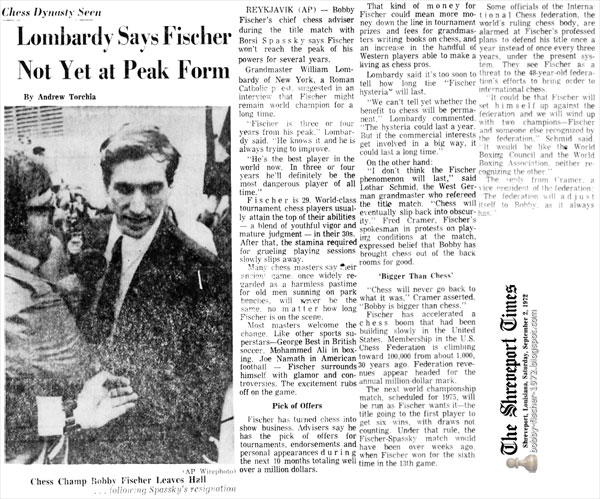

Lombardy Says Fischer Not Yet at Peak Form

Reykjavik (AP) — Bobby Fischer's chief chess adviser during the title match with Boris Spassky says Fischer won't reach the peak of his powers for several years.

Grandmaster William Lombardy of New York, a Roman Catholic priest, suggested in an interview that Fischer might remain world champion for a long time.

“Fischer is three or four years from his peak,” Lombardy said. “He knows it and he is always trying to improve.

“He's the best player in the world now. In three or four years he'll definitely be the most dangerous player of all time.”

Fischer is 29. World-class tournament chess players usually attain the top of their abilities — a blend of youthful vigor and mature judgement — in their 30s'. After that, the stamina required for grueling playing sessions slowly slips away.

Many chess masters say their ancient game, once widely regarded as a harmless pastime for old men sunning on park benches, will never be the same, no matter how long Fischer is on the scene.

Most masters welcome the change. Like other sports superstars—George Best in British soccer, Mohammad Ali in boxing, Joe Namath in American football — Fischer surrounds himself with glamor and controversies. The excitement rubs off on the game.

Pick of Offers

Fischer has turned chess into show business. Advisers say he has the pick of offers for tournaments, endorsements and personal appearances during the next 10 months totaling well over a million dollars.

That kind of money for Fischer could mean more money down the line in tournament prizes and fees for grandmasters writing books on chess, and an increase in the handful of Western players able to make a living as chess pros.

Lombardy said it's too soon to tell how long the “Fischer hysteria” will last.

“We can't tell yet whether the benefit to chess will be permanent,” Lombardy commented. “The hysteria could last a year. But if the commercial interests get involved in a big way, it could last a long time.”

On the other hand:

“I don't think the Fischer phenomenon will last,” said Lothar Schmid, the West German grandmaster who refereed the title match. “Chess will eventually slip back into obscurity.” Fred Cramer, Fischer's spokesman in protests on playing conditions at the match, expressed belief that Bobby has brought chess out of the back rooms for good.

‘Bigger Than Chess’

“Chess will never go back to what it was,” Cramer asserted. “Bobby is bigger than chess.”

Fischer has accelerated a chess boom that had been building slowly in the United States. Membership in the U.S. Ches Federation is climbing toward 100,000 from about 1,000 30 years ago. Federation revenues appear headed for the annual million dollar mark.

The next world championship match, scheduled for 1975, will be run as Fischer wants it—the title going to the first player to get six wins, with draws not counting. Under that rule, the Fischer-Spassky match would have been over weeks ago, when Fischer won for the sixth time in the 13th game.

Some officials of the International Chess federation, the world's ruling chess body, are alarmed at Fischer's professed plans to defend his title once a year instead of once every three years, under the present system. They see Fischer, as a threat to the 48-year-old federation's efforts to bring order to international chess.

“It coudl be that Fischer will set himself up against the federation and we will wind up with two champions—Fischer and someone else recognized by the federation,” Schmid said. “it would be like the World Boxing Council and the World Boxing Association, neither recognizing the other.”

The reply from Cramer, a vice president of the federation: “The federation will adjust itself to Bobby, as it always has.”

The Times Shreveport, Louisiana Saturday, September 02, 1972 - Page 9

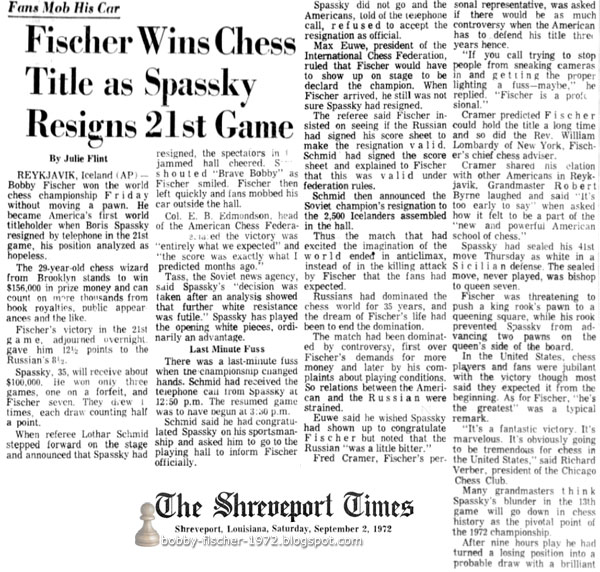

Fischer Wins Chess Title As Spassky Resigns 21st Game

By Julie Flint

Reykjavik, Iceland (AP)—Bobby Fischer won the world chess championship Friday without moving a pawn. He became America's first world titleholder when Boris Spassky resigned by telephone in the 21st game, his position analyzed as hopeless.

The 29-year-old chess wizard from Brooklyn stands to win $156,000 in prize money and can count on more thousands from book royalties, public appearances and the like.

Fischer's victory in the 21st game, adjourned overnight, gave him 12½ points to the Russian's 8½.

Spassky, 35, will receive about $100,000. He won only three games, one on a forfeit, and Fischer seven. They drew (illegible) times, each draw counting half a point.

When referee Lothar Schmid stepped forward on the stage and announced that Spassky had resigned, the spectators in the jammed hall cheered. Some shouted “Brave Bobby” as Fischer smiled. Fischer then left quickly and fans mobbed his car outside the hall.

Col. E.B. Edmondson, head of the American Chess Federation (illegible) the victory was “entirely what we expected“ and “the score was exactly what I predicted months ago.”

Tass, the Soviet news agency, said Spassky's “decision was taken after an analysis showed that further white resistance was futile.” Spassky has played the opening white pieces, ordinarily an advantage.

Last Minute Fuss

There was a last-minute fuss when the championship changed hands. Schmid had received the telephone call from Spassky at 12:50 pm. The resumed game was to have begun at 3:30 p.m.

Schmid said he had congratulated Spassky on his sportsmanship and asked him to go to the playing hall to inform Fischer officially.

Spassky did not go and the Americans, told of the telephone call, refused to accept the resignation as official.

Max Euwe, president of the International Chess Federation, ruled that Fischer would have to show up on stage to be declared the champion. When Fischer arrived, he still was not sure Spassky had resigned.

The referee said Fischer insisted on seeing if the Russian had signed his score sheet to make the resignation valid. Schmid had signed the score sheet and explained to Fischer that this was valid under federation rules.

Schmid then announced the Soviet champion's resignation to the 2,500 Icelanders assembled in the hall.

Thus the match that had excited the imagination of the world ended in anticlimax, instead of in the killing attack by Fischer that the fans had expected.

Russians had domination the chess world for 35 years, and the dream of Fischer's life had been to end the domination.

The match had been dominated by controversy, first over Fischer's demands for more money and later by his complaints about playing conditions. So relations between the American and the Russian were strained.

Euwe said he wished Spassky had shown up to congratulate Fischer but noted that the Russian “was a little bitter.”

Fred Cramer, Fischer's personal representative, was asked if there would be as much controversy when the American has to defend his title three years hence.

“If you call trying to stop people from sneaking cameras in and getting the proper lighting a fuss—maybe,” he replied. “Fischer is a professional.”

Cramer predicted Fischer could hold the title a long time and so did the Rev. William Lombardy of New York, Fischer's chief chess adviser.

Cramer shared his elation with other Americans in Reykjavik. Grandmaster Robert Byrne laughed and said “It's too early to say” when asked how it felt to be a part of the “new and powerful American school of chess.”

Spassky had sealed his 41st move Thursday as white in a Sicilian defense. The sealed move, never played was bishop to queen seven.

Fischer was threatening to push a king's rook pawn to a queening square, while his rook prevented Spassky from advancing two pawns on the queen's side of the board.

In the United States, chess players and fans were jubilant with the victory though most said they expected it from the beginning. As for Fischer, “he's the greatest” was a typical remark.

“It's a fantastic victory. It's marvelous. It's obviously going to be tremendous for chess in the United States,” said Richard Verber, president of the Chicago Chess Club.

Many grandmasters think Spassky's blunder in the 13th game will go down in chess history as the pivotal point of the 1972 championship.

After nine hours play he had turned a long position into a probable draw with a brilliant

defense, only to err on the 69th move and lose.

“Spassky should have drawn and the whole match would have been different,” said Jens Enevoldsen, a chess master from Denmark. “That defeat shook him so much that he lost a win for a draw in the next game.”

Fr. Lombardy, Fischer's chess second, said the 13th game—on Aug. 11—was so tough that “both players played the next one as if they were drunk.”

Euwe, a former world champion, agree that “this match was better than most others.”

Schmid, however, said he thought the match contained fewer than 10 games worthy of championship play and that tension led the players into “four or five terrible blunders.”

Some grandmasters thought the eight game, on July 27, was the worst in Spassky's career. He flubbed with what experts called a beginner's mistake and fell behind 5 points to 3. For the first time the home folks in Moscow thought Spassky might lose his title.

Euwe thought Fischer's best game was his victory in the 10th on Aug. 4.

Yugoslav Grandmaster Sovetozar Gligoric said Spassky could have fought on in the game Friday but had made a weak sealed move, instead of his bishop to queen seven, a starting move, the Russian should have played king to king(illegible) three, getting in front of Fischer's advancing pawn, Gligoric added.

“But Spassky lacked the energy to fight.” Gligoric said.

The Russian evidently decided to resign following overnight analysis that disclosed the weakness of his sealed move.

Gligoric said Fisher nearly let Spassky off the hook with his 40th and final move of the match Thursday. That was an advance of his king's rook pawn to the fourth rank. But Spassky did not find the right continuation.

Spassky lost the crown in his first defense, three years after taking it from Tigran Petrosian, another Russian.

It was a heart-breaking match for Spassky, who never before had lost a game to Fischer.

Spassky won the first game on a Fischer blunder and the second when the American forfeited rather than play with movie cameras in the hall.

The American won the third game, played in a back room away from the audience, and this seemed to break Spassky's spirit.

Fischer was in the lead by the sixth game. He built up a three-point lead at the 10th game. Spassky won the 11th game but lost the 13th with a blunder. That was the match.

Seven draws followed, an unusually long string for the aggressive Fischer, before he won the 21st game.

Fischer, who says he plays to crush his opponents' spirits and like to see them squirm, was devastating in the elimination matches leading to the championship.

He defeated Soviet grandmaster Mark Taimanov 6-0 and repeated the score against Bent Larsen of Denmark, generally considered the second-best player in the West.

Then Fischer toppled Petrosian 6½ to 2½ to gain the right to meet Spassky.

Fr. Lombardy said he never doubted that Fischer would defeat Spassky, even when trailing the Russian by two points after two games.

He said he had told Fischer that he expected an American victory even if Fischer had fallen three or four points behind.

Fischer had balked at coming to Iceland because the prized put up by the Icelandic Chess Federation was only $125,000. Yugoslavia had backed out as an original cosponsor because of Fischer's money demands. The winner gets five-eighths of the purse; the loser three-eighths.

He left New York for Reykjavik only after a British financier and chess fan, James D. Slater, doubled the purse to $250,000.

Spassky then refused to open the match until Fischer apologized for his “petty dispute over money.”

With Fischer's apology, the match began July 11, nine days late.

The Icelandic Chess Federation will throw a banquet for the contestants Sunday.