The Daily Journal Vineland, New Jersey Thursday, March 02, 1972 - Page 19

Caesars Palace Tops Yugoslavia's Bid for the Bobby Fischer-Russki Chess Championship

Caesars Palace topped Yugoslavia's bid for the Bobby Fischer-Russki chess championship ($175,000 to the Yugo $153,000) … The players decided Caesars Palace has too many distractions. Of course it has.

The Daily Plainsman Huron, South Dakota Thursday, March 02, 1972 - Page 4

Stalling The Checkmate

Summitry its problems. Merely making the preliminary arrangements so the main event can take place can tax the expert diplomat.

In arranging such a relatively simple matter as a champion chess match between Bobby Fischer of the United States and Boris Spassky of the Soviet Union, the initial conditions have proved troublesome.

Among the first decisions to be made was a site for the contest. The contestants opted for different locales and neither budged.

So the International Chess Federation settled that question by ruling the first half of the match would he held in Belgrade, Yugoslavia (Fischer's choice) and the second half in Reykjavik, Iceland (Spassky's selection).

Now the negotiators move on to other matters. Before much more effort has been expended on the tedious maneuverings, someone might well ask why the games cannot be played by mail. Providing an agreement could be reached on a courier, that is.

The Tampa Times Tampa, Florida Saturday, March 04, 1972 - Page 5

Refugee from Reds is No. 2 U.S. Chess Genius

When Russian tanks rolled into Czechoslovakia in 1968, chess grandmaster Lubomir Kavalek decided it was time to get out.

The 24-year-old genius was already famous in his homeland as one of the world's leading players, but he knew that wouldn't make any difference.

Much more important to the Communists was the fact that his movie director father had left the country in 1949 to work for Radio Free Europe —not exactly the credentials to make the Kavalek family a favorite of the regime.

The Russian power play thus became the young man's invitation to make a quick exit or risk unpleasant consequences. He chose the former course. Now as a somewhat delayed result the United States has a new world class player who ranks second on the rating list of his adopted country.

Bobby Fischer, of course, is No. 1. Just about everybody knows that by now. But how many Americans could name No. 2?

Try out the name Lubomir Kavalek on the next person you meet, and see if you get anything more than a blank stare and a set of directions to UN headquarters.

Such is the fate of the chess master in this land where the Joe Namaths, the Arnold Palmers and the Willie Mays are kings.

Kavalek's importance to the American chess scene, though, can hardly be overemphasized. The brilliant Czech refugee is looking forward to representing his new country in the chess Olympics at Skopje, Yugoslavia, next fall — and his presence there will give the U.S. team a much better chance of emerging victorious.

Meanwhile, he keeps busy playing in tournaments, working as a writer, broadcaster and translator for the Voice of America, and telling anyone who wants to listen how he found life under communism.

“I had some difficulties with the regime,” he says. “I wanted to study acting or directing, but I wasn't allowed to. Eventually I became a journalist, working for newspapers and magazines, but I felt there was no possibility of writing what I wanted with complete freedom.

“Under a regime like that, you're a machine. The orders come from upstairs. Even after I became famous in chess, I couldn't go to the West to compete in a tournament unless someone came along to watch over me.”

Kavalek's chess career began at the age of 11, when he learned the game from some friends and immediately took to it.

“I was so ambitious that within half a year I called Pachman (Ludek Pachman, a grandmaster and Czechoslovakia's leading player at the time; he has since been arrested and imprisoned by the current regime),” Kavalek recalls.

“It was my Christmas wish that year to play against him,” Kavalek says. “He agreed to meet me, and he explained that chess is not so easy.”

So young Kavalek studied and developed his obvious talent for a couple of years, then worked under Pachman's tutelage for two more.

“I went through theoretical books, and studied five or six hours a day,” he says. “By the time I was 15, I was already pretty strong. I won the championship of Prague. Then when I was 19, I became the youngest person ever to win the Czechoslovakian championship.”

What is it that separates a player of this caliber from the general run of chess enthusiasts? Can it be identified or analyzed?

“It's a matter of talent, but it's hard to describe,” he says. “Some people think it's a question of logic and science, but I still feel it's a game of imagination. Fantasy plays a big role. Also the will to work.”

When he was 21, Kavalek suffered a serious injury in a skiing accident. He lay immobile in a hospital for three months, then had to learn to walk all over again.

After his recovery, he concentrated on chess. He won the international master title, then surged to the international grandmaster rank (the highest there is) with a pair of successes in Bulgaria and East Germany.

And where does Lubomir Kavalek, who at 28 is the same age as Fisher, fit into today's scheme of things? Does he too have world title aspirations?

“If you don't have that ambition, you'd better stop playing chess,” he says. “However, I realize it's very hard to come close to such a player as Bobby if you are working and not playing chess full-time.”

Each world championship cycle runs three years, starting with zonal tournaments around the globe and culminating in the title match. After failing to qualify in 1967, Kavalek had to pass up the 1970 preliminaries while he was moving from country to country, but he plans to compete again in the new cycle which will begin late this year.

“Let's say I'm a little bit skeptical about myself,” he says, “but I feel I have to try.”

The Montana Standard Butte, Montana Saturday, March 04, 1972 - Page 7

Chess Master Gets Ultimatum

Belgrade, Yugoslavia (AP)—The president of the International Chess Federation said Friday that world champion Boris Spassky must forfeit his title if he refuses to accept the venue set for his match with Bobby Fischer.

Euwe ruled that the 24 games would be divided equally between Belgrade and Reykjavik, Iceland.

The Courier-Journal Louisville, Kentucky Saturday, March 04, 1972 - Page 22

The president of the International Chess Federation, Dr. Max Euwe, said that world champion Boris Spassky must forfeit his title if he refuses to accept the venue set for his match with Bobby Fischer. The Soviet world champion and the U.S. challenger failed earlier to agree on a match site and Euwe ruled that the 24 games would be divided equally between Belgrade and Reykjavik, Iceland. Spassky protested the decision.

New York Times, New York, New York, Sunday, March 05, 1972 - Page 56

Soviet Union Accepts Belgrade and Reykjavik as Title Chess Sites

New York Times, Moscow, March 4—The Soviet Union, in a major concession, agreed today to having the chess world championship match between Boris Spassky, the Soviet titleholder, and Bobby Fischer, the American challenger, held in two European cities.

The agreement, to play the first half of the match in Belgrade, the site preferred by Mr. Fischer, and the second half in Reykjavik, Iceland, which was Mr. Spassky's first choice, represented a compromise after the two players had failed to agree on a single city.

The compromise had been proposed by Dr. Max Euwe, chairman of the World Chess Federation, under international rules that gave him the right to fix a championship site if the two sides did not reach agreement.

The Soviet Union declared at first that it did not feel itself bound by Dr. Euwe's ruling on the ground that he had previously violated regulations by extending a deadline for submission of preferred match sites by Mr. Fischer.

However, the Soviet Chess Federation relented after Dr. Euwe went to Moscow this week in an apparent attempt to persuade the Russians to agree to the compromise.

A Soviet statement, made public by Tass, the official press agency, said the Russians were ready in principle to discuss the two-city compromise, although they continued to contend that the compromise was contrary to established procedure of playing the 24-game match in a single city.

In a letter signed by Victor Baturinsky, director of the Central Chess Club of the Soviet Union, and handed to Dr. Euwe after discussions here, the Russians agreed to meet in a few days with chess representatives from the United States, Yugoslavia and Iceland to discuss details.

The meeting was expected to be held next Friday in Amsterdam, headquarters of the International Federation. Under the rules, the world championship match must start by July 1.

Belgrade Offers $152,000

Mr. Fischer, who won the right to challenge Mr. Spassky by defeating Tigran Petrosian of the Soviet Union in the final elimination round, was understood to have preferred Belgrade, on the ground that it offered the largest cash prize—$152,000. The winner of the match is to get 62.5 per cent and the loser 37.5 per cent.

Mr. Spassky's choice of Reykjavik was based on his preference for a European city whose summer climate would be closest to that in his native Leningrad. He has found Belgrade too warm for his comfort in summer.

Iceland offered a $125,000 purse for the entire match. One of the problems that must be resolved in the final discussions, is the division of the cash prizes between the two cities.

Dayton Daily News Dayton, Ohio Sunday, March 05, 1972 - Page 4

Russians Agree To Chess Sites

Moscow (AP)—The Russian Chess Federation indicated on Saturday it would agree to two sites for the world championship chess match between Bobby Fischer of the United States and the Soviet Union's Boris Spassky.

The indication came in a letter which the Russian federation handed to Dr. Max Euwe, president of the International Chess Federation.

Euwe came to Moscow to try to break an impasse over the location for the championship match.

The Soviet news agency Tass reported that the Soviet federation said in the letter it is “ready, in principle, to discuss conducting the first half of the match in Belgrade and the second half in Reykjavik.”

Belgrade is in Yugoslavia and Reykjavik is in Iceland.

The Russians had said Spassky, the defending champion, had objected to playing all the games in a European city with a hot climate in summer.

In their letter the Russians said the games should begin in Belgrade no later than July 1.

Spassky had picked Reykjavik as his first choice. Fischer had selected Belgrade because it had made the top money offer of $152,000 to host the match.

The championship match will be 24 games.

The Province Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada Tuesday, March 07, 1972 - Page 21

Soviets Ready to Negotiate Chess Match Site

(UPI) Moscow — The Soviet Chess Federation has said it is ready to start final negotiations for terms of the World Chess Championship match between Boris Spassky and American challenger Bobby Fischer.

Tass, the official news agency, said the federation sent a letter to the International Chess Federation president Max Euwe saying it wants to meet with all parties concerned to “thrash out all questions and to sign a final agreement.”

The letter said the Soviets were ‘ready, in principle, to study the question of holding the first half of the match in Belgrade and the second in Reykjavik before July 1.”

Daily News New York, New York Wednesday, March 08, 1972 - Page 187

OK Chess Super Bowl

Amsterdam, March 7 (Special) — Russia has accepted a compromise settlement of the dispute over where to hold the world chess championship tournament, Max Euwe, president of the International Chess Federation, announced today. The American challenger, Bobby Fischer, will meet the Soviet titleholder, Boris Spassky, in Belgrade for the first 12 games, then complete the contest in Reykjavik, Iceland. Belgrade, which bid the top $152,000 in prize money, was favored by Fischer. Spassky wanted Reykjavik, which guaranteed $125,000 in prizes. The tournament must begin before July 1.

OK Chess Super Bowl Wed, Mar 8, 1972 – 187 · Daily News (New York, New York) · Newspapers.com

OK Chess Super Bowl Wed, Mar 8, 1972 – 187 · Daily News (New York, New York) · Newspapers.com

Ukiah Daily Journal Ukiah, California Wednesday, March 08, 1972 - Page 5

Chess Buffs Invited to Join Club

Beginners at chess and those advanced in the game are all invited to join members of the newly formed Ukiah Chess Club at 8 p.m. Thursday at the First Presbyterian Church.

The new club is affiliated with the Central California Chess Association and the U.S. Chess Federation.

Chess is enjoying a new period of popularity, perhaps stimulated by the forthcoming world title match between Fischer (US) and Spassky (USSR).

The local club was formed to further the rapid growth in popularity in the game, according to Jack Alan Baskerville, president.

Progress Bulletin Pomona, California Wednesday, March 08, 1972 - Page 15

Future Chess Experts Blooming in Valley Wed, Mar 8, 1972 – Page 15 · Progress Bulletin (Pomona, California) · Newspapers.com

Future Chess Experts Blooming in Valley Wed, Mar 8, 1972 – Page 15 · Progress Bulletin (Pomona, California) · Newspapers.com

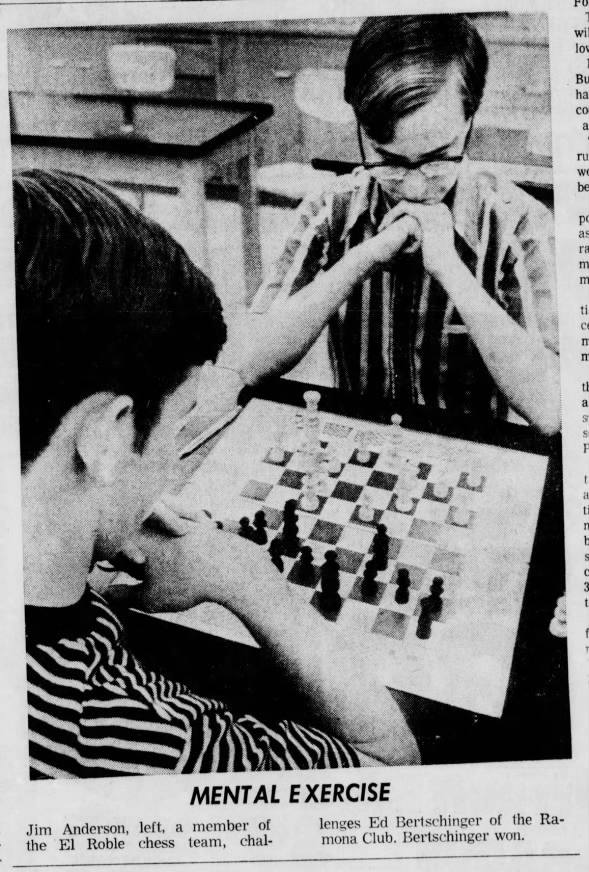

Mental Exercise

Jim Anderson, left, a member of the El Roble chess team, challenges Ed Bertschinger of the Ramona Club. Bertschinger won.

School Chess Tournament Keeps Boys Quiet Wed, Mar 8, 1972 – Page 15 · Progress Bulletin (Pomona, California) · Newspapers.com

School Chess Tournament Keeps Boys Quiet Wed, Mar 8, 1972 – Page 15 · Progress Bulletin (Pomona, California) · Newspapers.com

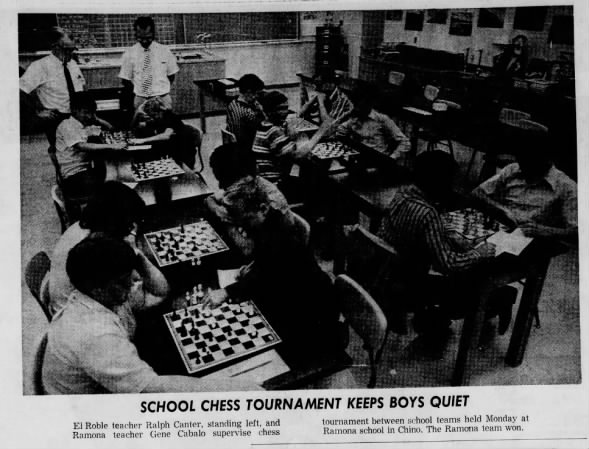

School Chess Tournament Keeps Boys Quiet

El Roble teacher Ralph Canter, standing left, and Ramona teacher Gene Cabalo supervise chess tournament between school teams held Monday at Ramona school in Chino. The Ramona team won.

Future Chess Experts Blooming in Valley Wed, Mar 8, 1972 – Page 15 · Progress Bulletin (Pomona, California) · Newspapers.com

Future Chess Experts Blooming in Valley Wed, Mar 8, 1972 – Page 15 · Progress Bulletin (Pomona, California) · Newspapers.com

Future Chess Experts Blooming in Valley

…Cabalo pointed out that for the first time in history of world championships an American chess player, U.S. champion Bobby Fischer, may soon have a chance to win the world championship currently held by Russia.

“Russian school children are taught chess. Those who show talent are sent to special schools,” Cabalo said.

Daily Independent Journal San Rafael, California Thursday, March 09, 1972 - Page 19

Birthday Quiz by Gordon B. Greb

Try this quiz about a famous person born today, March 9: Bobby Fischer (1943-), a brilliant American chess player:

1. Born in Chicago, Illinois, he began playing chess at the age of 6 and after moving to New York joined the Manhattan Chess Club.

TRUE—Yes, this “wonder child” of chess was beating Manhattan Club adults at the age of 12.

2. He dropped out of Erasmus Hall High School to concentrate on chess.

TRUE— But in 1959 his high school gave him a gold medal.

3. Fischer became U.S. champion when he was only 14 and took the national title eight times.

TRUE—He won the U.S. title every time he competed—eight times.

4. Nervous, moody, and easily distracted, some critics have termed his tournament behavior as that of “a small boy,” even though he is 29.

TRUE— The Russians especially have heaped scorn on Bobby for his attitude. #AutismAwareness. Antisemitic tournament organizers discriminated against Reshevsky and Fischer's worship on 7th day sabbath. Fischer walked out. Good for him.

5. Fischer became world champion recently by beating the great Russian, Boris Spassky—which has been the goal of his life-time.

FALSE—Fischer believes he is ready to defeat the Russian for the world title and a prize of ($5,000) but he has not done it yet.

Kenosha News Kenosha, Wisconsin Friday, March 10, 1972 - Page 27

Fischer Moves Against Foe

New York — Bobby Fischer could not have found a tougher opponent for the world chess championship than Boris Spassky of Russia, says Sports Illustrated this week.

Spassky, who has held the title since 1969, plays a dogged defense and possesses formidable attacking power, and in five tournament games up to now against Fischer he has won three, and there have been two draws.

THE 35-YEAR OLD Russian differs greatly in his approach to the game from Fischer, says Sports Illustrated. While Fischer seems to spend nearly all of his waking hours studying and analyzing, Spassky devotes no more than three or four hours a day to chess analysis. But while Fischer works alone, Spassky has a marvelous team to carry on for him.

The group consists of Igor Bondarevsky, 58, a former Soviet champion who has been Spassky's coach for a decade, and who seems (Spassky is unwilling to disclose the separate functions of his advisory team) to be in charge of overall match strategy and in particular, the task of determining what type of formation is best adapted to countering the individual psychology of the opponent.

Other members of the group includes Nikolai Krogius, a statistical psychologist whose function is cloudy, International Yefim Geller and Nei have between them an enormous amount of expertise on a broad spectrum of opening moves.

As for Spassky himself, he is extraordinary resilient, never so dangerous as in the next game after a loss.

Closely related to this is his delayed-likes to come out at the opening bell ready to flatten his opponent with the first punch, Spassky is often slow to take the initiative. He does not reach full power until early in the middle game. This pattern of play has a deceptive effect, lulling his opponent into a false sense of security just when the explosion is all set to go off.

“I'm lazy,” Spassky once said. “I'm like a Russian bear; calm, slow and finding it an effort to get up.”

Fischer's smashing victories on the path to the finals may have lulled U.S. observers into thinking that the way past Spassky will also be an easy one. Not so, says Sports Illustrated. As former world champion Mikhail Tal says, “Bobby won't have it so easy against Spassky.”

Long ago Spassky remarked that one thing that made him less valuable than Fischer was his ability to accept defeat. When asked how he avoided being discouraged and could snap back after a bad beating in a given game, he replied it was his secret and he was going to keep it.

The secret is something Fischer must bear in mind.

New York Times, New York, New York, Sunday, March 12, 1972 - Page 209

Chess: Nobody Seems Happy About It by Al Horowitz

An AP dispatch from Reykjavik, Iceland, in regard to the Fischer-Spassky match reads: “The president of the Icelandic Chess Federation expressed surprise at the decision to hold the world championship match in both Reykjavik and Belgrade, Yugoslavia.”

Gudmundur Thorarinsson said Iceland was not fully consulted and planned to seek clarification of the terms under which the match will be split. The International Chess Federation in Amsterdam announced that the Soviet titleholder, Boris Spassky, and the American challenger, Bobby Fischer, will play 12 games in Belgrade, the final 12 in Reykjavik.

Thorarinsson said an agreement between the two cities must be reached on how to split costs and payment of the winner's purse. “The match was divided because the players could not agree on a location for the match, set to begin no later than June 25. Spassky wanted Reykjavik, and Fischer favored Belgrade,” he added.

To boot, the Russians have indicated a protest was forthcoming from their end, which means at least another week will go by before the venue is clear.

A treasury of Spassky victories has come to hand from the 9th Canadian Open held last year at Vancouver, Canada. The event, a Swiss System, attracted an entry of 156, of which 40 were American.

Before the second last round, Walter Browne of Australia, Hans Ree of Holland and Duncan Suttles of Canada were leading with 7½ each. Spassky trailed with 7. In the last round, Browne and Ree drew, as did Suttles and Kavalek. But Spassky won from Kuprejanov and pulled up to the leading Ree. Thus, the finish saw Spassky and Ree in a first-place tie with 9 points; Suttles, Vranesic and Browne with 8½, and others following.

Spassky-Zuk is a King's Indian Defense, one of Fischer's favorites. It may therefore, serve as a cardinal example to observe White's treatment—the opening deployment and the follow-up campaign.

The line that Black uses, however, is not orthodox. Black, for example, fianchettoes his queen-bishop and permits White to continue with 9. P-Q5, cutting the scope of the bishop. Undoubtedly, the bishop is better on its original square. Black, therefore, should not play as Zuk. There are many alternatives.

During the first ten moves in a game, there are infinite possibilities. It has been reckoned as the digit 1 with 30 zeroes. This delineates the problem.

In the Sicilian Defense with Kuprejavov, it is interesting to observe Spassky's treatment. For here, again, the Sicilian is a favorite of Fischer, White enters a profound combination, “sacking” a knight, before he has contemplated its recovery.

As in most deep combinations, it is important to see the denouement from beginning to end before establishing a reputation for courage. Now, Black picks a tail-end flaw in the technique, as expected, and White must resign.

In the Center Counter Defense, Spassky vs. Banks of Canada, the Canadian ventures on a line academically unsound. For in the opening, after 2. PxP, Black can hardly afford 2. … QxP at the cost of a precious tempo, 3. N-Q3.

In the circumstances, Black plays 2. … N-KB3, trusting to recover the pawn without incurring any weaknesses. Without much precedent for the line, the players are on their own. White could obtain the edge, for example, with 11. NxB, followed by 12. P-Q4 — the bishop for the knight — but by attrition the position follows reductio ad absurdum and the edge is patently minimal.

Black executes a stratagem with 22. … BxN. For White must recapture with the pawn. After 23. QxB, P-B4 opens critical lines to White's king thus: 24. PxP PxP; 25. QxB QR-N1, threatening mate! Therefore, White lays the groundwork for a better ending or a powerful incursion. 33. BxPch spells finis.

Chicago Tribune Chicago, Illinois Sunday, March 12, 1972 - Page 356

Chess Mail

Chicago—Congratulation on your weekly chess column. The growth of chess in recent years has been nothing short of sensational; in metropolitan Chicago alone, there are almost 2,000 regular tournament players, 20,000 to 30,000 avid followers of chess news, and hundreds of thousands of persons interested in the impending Bobby Fischer-Boris Spassky world championship match.

You might be interested to learn that New York chess masters are picking Fischer over Spassky by a score of 12½-9½, the Las Vegas oddsmaker say Fischer 12½-8½, and in Chicago the top chess masters are predicting Fischer 12½-7½. World chess opinion—even in Communist Bloc countries—favors Fischer to defeat Spassky. -Richard W. Verber, President, Chicago Chess Club.

Arts & Fun Forum Sun, Mar 12, 1972 – 356 · Chicago Tribune (Chicago, Illinois) · Newspapers.com

Arts & Fun Forum Sun, Mar 12, 1972 – 356 · Chicago Tribune (Chicago, Illinois) · Newspapers.com

Sports Illustrated, March 13, 1972 - Page 22

The Big Burden Boris Bears by Robert Byrne

When Bobby Fischer sits down opposite Boris Spassky next June to settle the question of whether an American has truly overtaken a Russian as the world's best chess player, it will mark a new high in awareness of the game in this country. But Fischer's smashing victories en route to the finals against the world champion may have lulled casual U.S. observers into thinking the rest of the way will be easy too. Not so. What has gone before has no more bearing on the championship matches than a runaway pennant race has to do with the outcome of a World Series.

Fischer's opponent, in a sense, is the Soviet Union itself. In addition to the spurs of personal pride and competitiveness that will be driving Spassky, he will also be out to uphold his nation's honor in a field it has dominated for a

quarter century. He is well trained to uphold it, and even now is undergoing intensive preparation with the top chess theoreticians in the world—all of whom share his dedication to continued Soviet preeminence in chess.

Consequently, Spassky is under heavy pressure, and he is showing it. Some of the pressure comes from the Soviet Ministry of Physical Culture and Sport, which for a generation convinced the rest of the world that chess supremacy was a Russian prerogative. Last December in Moscow, Spassky's flagging spirits were conspicuously in evidence. The 35-year-old champion was competing in the month-long Alekhine Memorial Tournament along with 18 high-ranking contenders, including Tigran Petrosian, who had just returned from being clobbered by Fischer at Buenos Aires (SI, November 8, 1971). A world champion is not expected to take first place every time he enters a tournament of this class, but it was not a good moment for Spassky to finish in a tie for sixth. Another bad omen was his resounding defeat by Petrosian. My own game with Spassky was drawn (I finished half a point behind him in the final standings) and it seemed to me there was a lackluster, uncertain quality to his play that had not characterized it in the past. His performance legitimately stirs some interesting speculation.

What sort of man is the champion? Spassky is not a simple person; no superior chess player is. He is a green-eyed, broad-shouldered man with reddish-brown hair who dresses with an air of studied elegance. He is 5' 10", weighs 176 pounds, has a trim figure and gives an impression, at a first meeting, of being a superior physical athlete, say a tennis or soccer player. Indeed, tennis and soccer are two of his favorite sports, but he also goes in for swimming, running and skiing.

Spassky and his second wide Larissa and their 4-year-old son live on the fifth floor of Moscow's newest and largest apartment building. He is one of the few Russians who drive a foreign car, a bright-red Volvo he bought after Russia won the 1970 International Team Tournament in West Germany. By Soviet standards he has a good income, something in excess of 500 rubles ($560) a month, which is five times more than the average worker gets. He could easily augment this with exhibitions and lectures, but he does not have the slightest inclination to do so, and he rarely writes on chess, although he has a degree in journalism from the University of Leningrad.

Underneath his easygoing, good-natured manner, Spassky is tough and determined. Talking with him in Moscow last December I remarked that he seemed a natural competitor. He demurred. “No,” he said, “my profession makes me so.” But he knows the need for the enormous competitive effort required in top-level chess. During his first try for the world championship in 1966, when he was defeated by Petrosian (four losses, three wins and 17 draws), Spassky lost 15 pounds. In their second match in 1969, when Spassky came back to take the title (six wins, four losses and 13 draws), he lost five pounds. After that victory his wife offered reporters a glimpse of life with a champion. “I would not like our son to play chess,

because the nervous strain is too great,” she said. “It was very difficult to watch all this happening.”

Spassky moved into the Leningradskaya Hotel by himself for the Alekhine tournament. In the past, after his tournament games he often played bridge with his chess opponents. “We used to play every night,” he said, “and my chess game did not suffer.” But he did not play bridge this time.

The good wishes Spassky gets from rivals and friends in Moscow for his match with Fischer are little comfort to him. At best these sound like the sort of encouragement Columbus received before he set out on his voyage in 1492. Or, more like it, the kind the Pittsburgh Pirates would get it they were suddenly meeting a favored foreign team—say the Tokyo Giants—in the World Series for the first time. Ever since 1948, when Mikhail Botvinnik first brought the world championship to the Soviet Union after the death of Alexander Alekhine, one Soviet star after another has kept the title there. During the intervening 24 years even the challengers have come from the Soviet Union. In the circumstances, the government could well afford to remain neutral about the fate of the champion. Indeed, a periodic turnover of the championship was welcomed, so long as it was turned over to another Soviet player. Such a turnover, in the eyes of the government, demonstrated the superiority of Soviet players as a class. In international terms, the underlying idea was to use chess as a showcase in which the superiority of the Communist system could be displayed.

Chess domination by the Soviet Union is not an accidental phenomenon. Russian youth is led into the game and schooled in its subtleties much as American youngsters learn about baseball. The Russian youth competes in local chess clubs instead of Little League. He may also join a team at school, where the game is offered as part of the regular curriculum. Gifted youngsters get further encouragement through larger clubs and by entering tough regional tournaments. Eventually, such a youth might enter a chess institute for advanced players—the graduate schools of Russian chess— where he gets special instruction from the world's best players.

Even after a player has achieved international recognition he may still occasionally return to the institute for refresher courses, as an American touring golfer might seek out his teaching pro when his game goes sour. Yuri Balashov, who finished fourth in the last Soviet championship, returned to his chess institute for further work after making a poor showing in last year's Alekhine tournament.

A primary incentive to the Soviet chess player is money. A good player, even though hardly in Spassky's class, earns a state salary well above that of the average worker, and his schedule is arranged to avoid physical or mental strain. Such are the perquisites of a national institution.

But Fischer's victories may be changing everything—including, apparently, the tractability of the Soviet Chess Federation, which had been making an unprecedented fuss over the match site. Spassky is going into battle not as a lone combatant confronting his foremost rival, but as a towering rampart defending Soviet tradition. Bearing the standard of his country's national sport would be an oppressive psychological burden for anyone. But when added to the normal anxieties preceding a championship match, the pressure could be overwhelming.

Nor is this the only cause of Spassky's gloom these days. Fischer won the right to challenge him in a fashion so spectacular as to unnerve any opponent—six straight wins against the U.S.S.R.'s formidable Mar Taimanov, six straight against Bent Larsen of Denmark, and at Buenos Aires four straight closing wins against Petrosian. Thus, his qualifying tournament record stands at 17 wins, one loss and three draws. (Spassky, on his way to the championship in 1968 against Geller, Larsen and Korchnoi, scored 11 wins, 13 draws and one loss.)

Spassky has no intention of becoming the scapegoat in a Russian catastrophe, however. He is extraordinarily resilient, never so dangerous as in the next game after a loss. Closely related to this is his delayed-action style of chess. Unlike Fischer, who comes out at the sound of the bell ready to flatten his opponent with the first punch, Spassky is often slow to take the initiative. He does not reach full power until early in the middle game. This pattern of play has a deceptive effect, lulling his opponent into a false sense of security just when the explosion is all set to go off.

“I'm lazy,” Spassky once said. “I'm like a Russian bear—calm, slow, and finding it an effort to get up.” Compared to Fischer, who seems to spend every waking hour studying and analyzing, Spassky devotes no more than three or four hours a day to chess analysis. But Fischer works alone, while Spassky has a marvelous team to carry on for him.

Presiding over the group is Igor Bondarevsky, 58, a former Soviet champion who has been Spassky's coach for the past decade. Bondarevsky came into Spassky's life at a low point in his career. In the world student championship in Leningrad in 1960, playing first board, Spassky was decisively beaten by William Lombardy of the U.S. in only 29 moves, a loss that won the tournament for the American team. Spassky was blamed for the Soviet defeat. He also quarreled with his coach, the brilliant but domineering Alexander Tolush, and the pressures of divorce proceedings from his first wife further disconcerted him. Finally he was so out of favor with Soviet chess authorities that he was forbidden to play abroad for three years. “Bondarevsky did a lot not only for my chess knowledge but for my character,” Spassky once said. “He has a very happy family life, and he is a man of strong character.”

Spassky is unwilling to disclose the separate functions of the members of his advisory team, but Bondarevsky seems to be in charge of overall match strategy and, in particular, the task of determining what type of formation is best adapted to countering the individual psychology of each opponent. It was said in Moscow that Bondarevsky was responsible for Spassky's brilliant use of the ancient Tarrasch Defense when he won the championship from Petrosian in 1969. Certainly Spassky has been extraordinarily skillful at playing on his rivals' weaknesses. But what will Bondarevsky suggest for the games against Fischer, who does not seem to have any obvious weakness?

Another member of Spassky's group is Nikolai Krogius, 41, a mild-mannered, scholarly statistical psychologist, and a frequent opponent of Spassky's in his early career. Krogius has been cast in a Svengalian role by some, but his real function seems far more mundane. Spassky once was asked exactly what Krogius did on his team. “He gives homey

advice and platitudes,” answered the champion, “to which the rest of us listen with rapt attention.”

For analysis of openings and end games during adjustments, Spassky has acquired the services of Yefim Geller (also once coached by Bondarevsky) and Geller's assistant, Ivo Nei. During the 1962 International Team Championship at Varna, in the first meeting between Botvinnik and Bobby Fischer, the game was adjourned with Botvinnik in a difficult position. When the adjournment was played off, Botvinnik escaped with a draw, and he gave Geller the credit for having discovered in overnight analysis the way to equalize the game. Between them, Geller and Nei have an enormous amount of expertise on a broad spectrum of openings.

Bondarevsky says that Spassky will beat Fischer. But most Soviet experts are skeptical or noncommittal. Botvinnik has said that however the match turns out, Fischer and Spassky will continue to have seesaw battles for a decade. A Yugoslav journalist found Petrosian playing a slot machine at the Moscow Writers' Club after his lopsided loss to Fischer and asked him the obvious question. “The world waits for a new king on the chess throne,” Petrosian replied, “I cannot say who this will be, nor am I able to forecast the future … Is Fischer really a chess genius? I am absolutely sure he is not.”

Viktor Korchnoi says that Fischer will win because Spassky is lazy. Spassky's most ebullient supporter is the former world champion Mikhail Tal, who says “Bobby won't have it so easy against Spassky.”

In spite of the underlying Soviet pessimism, Spassky's fears and Fischer's fabulous feats, Tal is right. With Spassky's dogged defense and formidable attacking power, Fischer could not find a tougher opponent. Spassky and Fischer have played five tournament games in the past. Spassky won three, and two were drawn, but all were played before Fischer's sensational winning streak began. Long ago Spassky remarked that one thing that made him less vulnerable than Fischer was his ability to accept defeat. When asked how he avoided being discouraged and could snap back after a bad beating in a given game, he replied that this was his secret and he was going to keep it. The secret is something Fischer must bear in mind. END

The Indianapolis Star Indianapolis, Indiana Thursday, March 16, 1972 - Page 35

Donald Byrne, Authors “Big Burden Boris Bears” in Sports Illustrated

An Indianapolis Man, Robert Byrne, is probably as qualified as anyone in the world to evaluate the upcoming world championship chess match between Russia's Boris Spassky and Bobby Fischer of the United States.

The match, which is certain to be the first chess match in history to rate headline coverage because of the political overtones, was discussed by Byrne in an article he penned for Sports Illustrated magazine last week.

Byrne, one of only seven International Grand Chess masters in the U.S., has beaten Fischer twice and has registered a draw with Spassky as recently as last May.

Byrne said preparation for the coming world championship match is unprecedented. Fischer is supposed to be studying films of Spassky in action in order to see how the Russian reacts to various situations on the board and which ones he finds the most difficult.

Donald Byrne - Sports Illustrated Thu, Mar 16, 1972 – Page 35 · The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana) · Newspapers.com

Donald Byrne - Sports Illustrated Thu, Mar 16, 1972 – Page 35 · The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana) · Newspapers.com

The Daily Herald Provo, Utah Friday, March 17, 1972 - Page 10

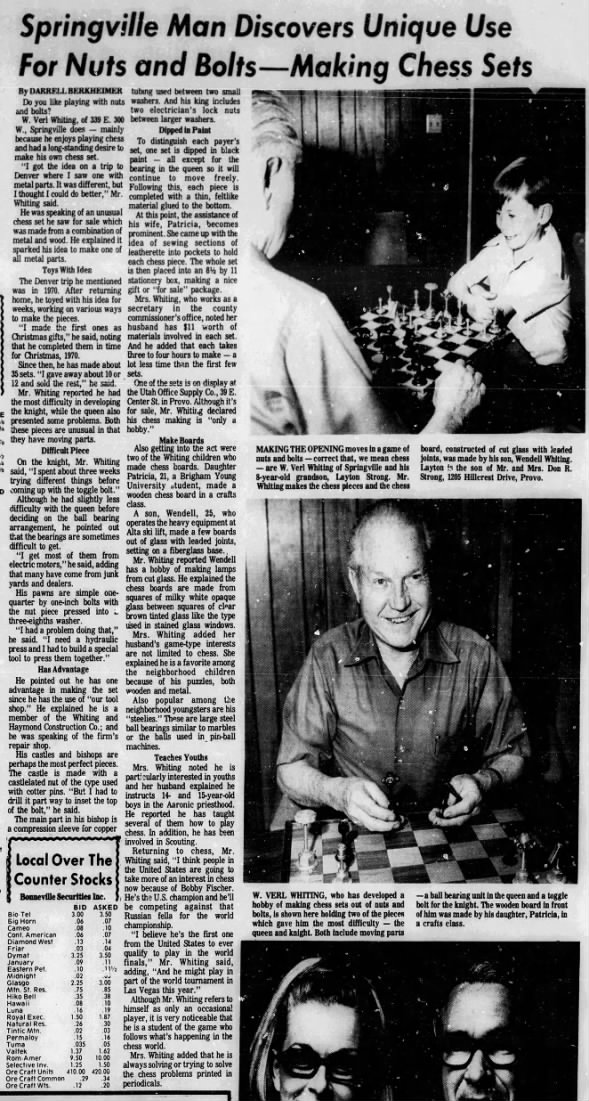

Springville Man Discovers Unique Use For Nuts and Bolts -- Making Chess Sets by Darrell Berkheimer

…

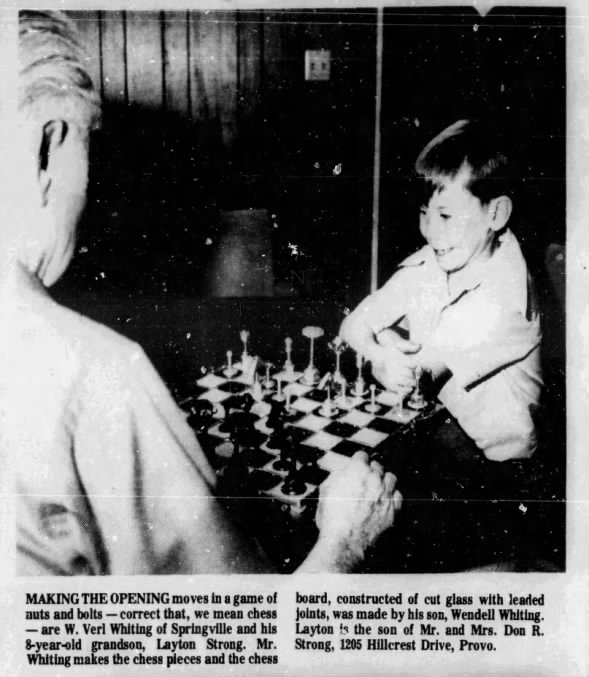

Teaches Youths

Mrs. Whiting noted he is particularly interested in youths and her husband explained he instructs 14 and 15 year old boys in the Aaronic priesthood. He reported he has taught several of them how to play chess. In addition, he has been involved in Scouting.

Returning to chess, Mr. Whiting said, “I think people in the United States are going to take more of an interest in chess now because of Bobby Fischer. He's the U.S. champion and he'll be competing against that Russian fella for the world championship.

“I believe he's the first one from the United States to ever qualify to play in the world finals,” Mr. Whiting said, adding “And he might play in part of the world tournament in Las Vegas this year.”

Although Mr. Whiting refers to himself as only an occasional player, it is very noticeable that he is a student of the game who follows what's happening in the chess world. …

Making The Opening Move Fri, Mar 17, 1972 – 10 · The Daily Herald (Provo, Utah) · Newspapers.com

Making The Opening Move Fri, Mar 17, 1972 – 10 · The Daily Herald (Provo, Utah) · Newspapers.com

Springville Man Discovers Unique Use For Nuts and Bolts -- Making Chess Sets Fri, Mar 17, 1972 – 10 · The Daily Herald (Provo, Utah) · Newspapers.com

Springville Man Discovers Unique Use For Nuts and Bolts -- Making Chess Sets Fri, Mar 17, 1972 – 10 · The Daily Herald (Provo, Utah) · Newspapers.com

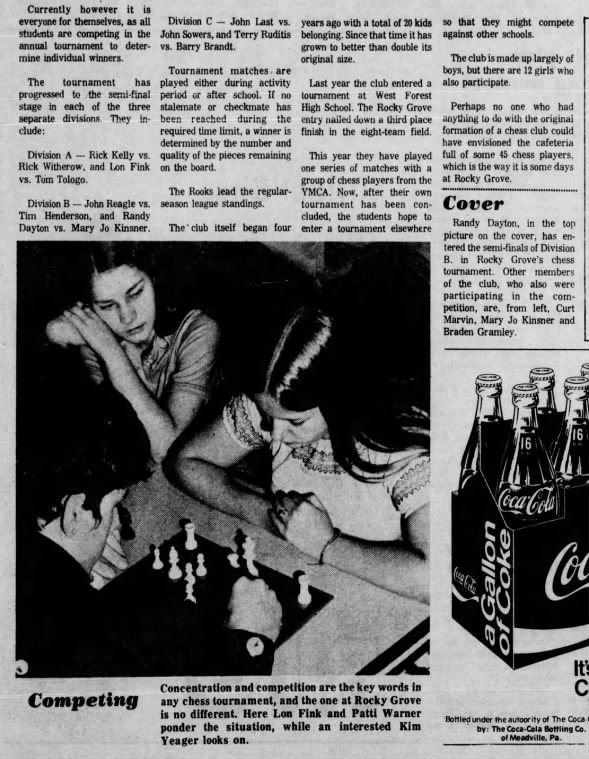

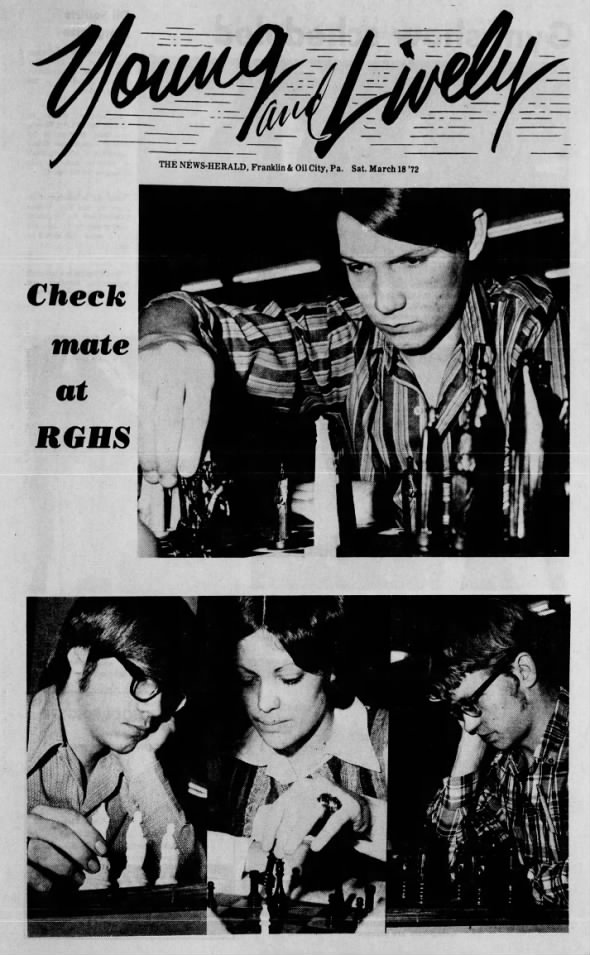

The News-Herald Franklin, Pennsylvania Saturday, March 18, 1972 - Page 9

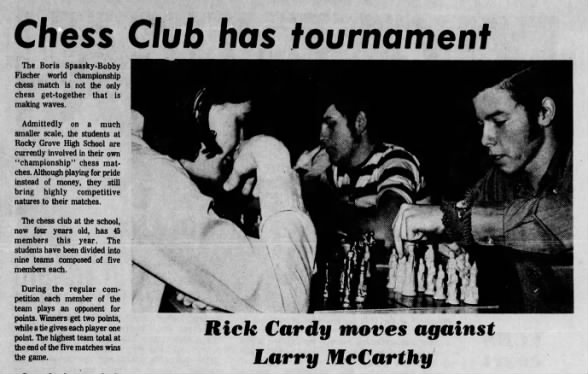

Checkmate at RGHS: Chess Club Has Tournament

The Boris Spassky-Bobby Fischer world championship chess match is not the only chess get-together that is making waves.

Admittedly on a much smaller scale, the students at Rocky Grove High School are currently involved in their own “championship” chess matches. Although playing for pride instead of money, they still bring highly competitive natures to their matches…

Chess Club Has Tournament Sat, Mar 18, 1972 – Page 9 · The News-Herald (Franklin, Pennsylvania) · Newspapers.com

Chess Club Has Tournament Sat, Mar 18, 1972 – Page 9 · The News-Herald (Franklin, Pennsylvania) · Newspapers.com

Competing

Chess Club Has Tournament Sat, Mar 18, 1972 – Page 9 · The News-Herald (Franklin, Pennsylvania) · Newspapers.com

Chess Club Has Tournament Sat, Mar 18, 1972 – Page 9 · The News-Herald (Franklin, Pennsylvania) · Newspapers.com

Cover

Randy Dayton, in the top picture on the cover, has entered the semi-finals of Division B. in Rocky Grover's chess tournament. Other members of the club, who also were participating in the competition, are, from left, Curt Marvin, Mary Jo Kinsner and Braden Gramley.

Checkmate at RGHS Sat, Mar 18, 1972 – Page 7 · The News-Herald (Franklin, Pennsylvania) · Newspapers.com

Checkmate at RGHS Sat, Mar 18, 1972 – Page 7 · The News-Herald (Franklin, Pennsylvania) · Newspapers.com

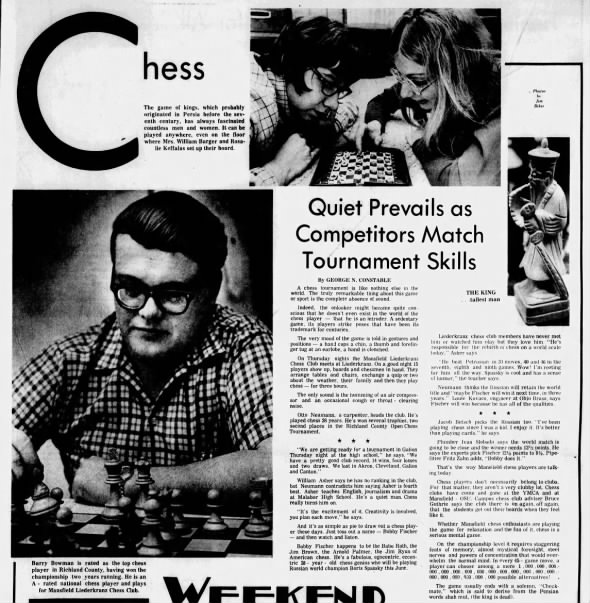

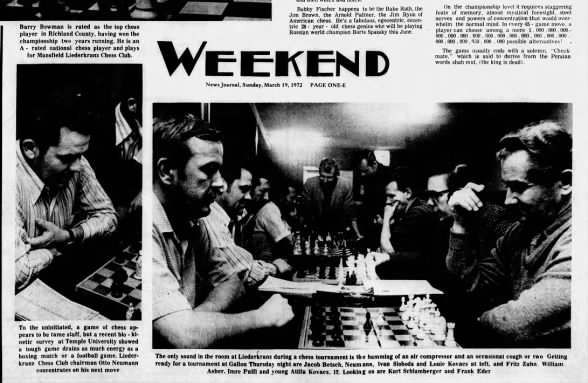

News-Journal Mansfield, Ohio Sunday, March 19, 1972 - Page 63

Chess: Quiet Prevails as Competitors Match Tournament Skills by George N. Constable

A chess tournament is like nothing else in the world. The truly remarkable thing about this game or sport is the complete absence of sound.

Indeed, the onlooker might become quite conscious that he doesn't even exist in the world of the chess player — that he is an intruder. A sedentary game, its players strike poses that have been its trademark for centuries.

The very mood of the game is told in gestures and positions — a hand cups a chin, a thumb and forefinger tug at an earlobe, a hand is clenched.

[…]

“It's the excitement of it. Creativity is involved, you plan each move,” he says.

And it's as simple as pie to draw out a chess player these days. Just toss out a name — Bobby Fischer — and then watch and listen.

Bobby Fischer happens to be the Babe Ruth, the Jim Brown, the Arnold Palmer, the Jim Ryun of American chess. He's a fabulous 28-year-old chess genius who will be playing Russian world champion Boris Spassky this June.

Liederkranz chess club members have never met him or watched him play but they love him. “He's responsible for the rebirth of chess on a world scale today,” Asher says.

“He beat Petrosian in 39 moves, 40 and 46 in the seventh, eighth and ninth games. Wow! I'm rooting for him all the way. Spassky is cool and has a sense of humor,” the teacher says.

Neumann thinks the Russian will retain the world title and “maybe Fischer will win it the next time, in three years.” Louis Kovacs, engineer at Ohio Brass, says Fischer will win because he has all of the qualities.

Jacob Betsch picks the Russian too. “I've been playing chess since I was a kid. I enjoy it. It's better than playing cards,” he says.

Plumber Ivan Sloboda says the world match is going to be close and the winner needs 12½ points. He says the experts pick Fischer 12½ points to 9½. Pipefitter Fritz Zahn adds, “Bobby does it.”.

That's the way Mansfield chess players are talking today.

Chess: Quiet Prevails as Competitors Match Tournament Skills Sun, Mar 19, 1972 – 63 · News-Journal (Mansfield, Ohio) · Newspapers.com

Chess: Quiet Prevails as Competitors Match Tournament Skills Sun, Mar 19, 1972 – 63 · News-Journal (Mansfield, Ohio) · Newspapers.com

Chess: Quiet Prevails as Competitors Match Tournament Skills Sun, Mar 19, 1972 – 63 · News-Journal (Mansfield, Ohio) · Newspapers.com

Chess: Quiet Prevails as Competitors Match Tournament Skills Sun, Mar 19, 1972 – 63 · News-Journal (Mansfield, Ohio) · Newspapers.com

The Sydney Morning Herald Sydney, New South Wales, Australia Sunday, March 19, 1972 - Page 48

Chess Men Ready For Big Tussle

Brisbane, Saturday. — Diplomacy will reign when chess giants Robert Fischer and Boris Spassky meet for the world chess championship on neutral ground later this year.

Half of the 24 matches will be played in Belgrade, Yugoslavia, and half in Reykjavik, Iceland.

Professor Max Euwe, president of the International Chess Federation, said in Brisbane today that Belgrade had been the choice of the American Fischer, while current world champ, Spassky chose Reykjavik.

The glamour boy of the American chessboards, Fischer, was quoted in January as saying he was sure he would be sabotaged if the play-off was held in Russia.

AGGRESSIVE

Professor Euwe said he thought the importance of Fischer's statement had been distorted.

The professor said he had seen both champions play and had noted their different techniques.

“I would say Spassky is a very aggressive player,” he said, “while Fischer is a strategist.”

Chess players were inclined to be temperamental under the stress of an important game.

Fischer had demanded complete silence and as far as possible this would be maintained.

The temperature in the playing-room would be maintained at a desirable level, neither too hot nor too cold.

There was also a clause in the conditions of play that prevented either player postponing games more than three times, the professor added.

“When a player loses two games in a row its quite common for him to develop a psychological illness and postpone the next one. This condition won't allow him to take his illness too seriously.”

Professor Euwe gave four reasons why Russia had dominated chess play for so long.

“First, its a big country with a big population: then it has long, cold winters—the right conditions for indoor games: The Slav races are artistic, imaginative and logical people — necessary qualities for a good chess player, and probably most important, the government sponsors the game as it does in no other country.”

The professor, who started playing at the age of 4 and rose to become world champion by 34 (in 1935) said he believed the game was a good mental discipline for young people.

The Vancouver Sun Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada Monday, March 20, 1972 - Page 9

Chess Battle Starts June 22

Amsterdam (AP) — The world chess title match between reigning champion Boris Spassky of the Soviet Union and U.S. challenger Robert Fischer starts in Belgrade, Yugoslavia, June 22, it was decided here today.

At stake besides the title is $138,500 in prize money, 72.5 per cent going to the winner and the remainder to the loser, a spokesman for the international Chess Federation said.

After 12 games the site switches to Reykjavik, Iceland, where the title contest will be continued Aug. 6.

The details were worked out at a meeting of representatives of the Yugoslav, Icelandic, Russian and American chess federations.

Chief referee will be the West German grandmaster Lothar Schmid.

If the final ends in a 12-12 draw, Spassky will retain his title and the prize money will be split between the two grandmasters.

The last Belgrade match is scheduled for Tuesday, July 18. If the match goes the full stretch of 24 games, the last game will be played in Reykjavik Aug. 31.

Fort Worth Star-Telegram Fort Worth, Texas Monday, March 20, 1972 - Page 10

Belgrade To Be Site of Chess Tilt

Amsterdam (AP) — Chess officials decided today the world title match between champion Boris Spassky of the Soviet Union and his U.S. Challenger Robert Fischer will begin in Belgrade, Yugoslavia, on June 22.

WIth the title goes $138,500 in prize money, 72½ per cent to the winner and the remainder to the loser, a spokesman for the International Chess Federation said.

After 12 games the match switches to Reykjavik, Iceland, where the title contest will be continued on Aug. 6.

The details were worked out at a meeting of representatives of the Yugoslav, Icelandic, Soviet and American chess federations.

If the match ends in a 12-12 draw, Spassky will retain his world title and the prize money will be evenly split.

The matches will be played three times a week. The last Belgrade match is scheduled for July 18. If the match goes the full stretch of 24 games, the last game will be played in Reykjavik on Aug. 31.

Hartford Courant Hartford, Connecticut Tuesday, March 21, 1972 - Page 28

Chess Federation Settles Details Of Championship

Amsterdam (UPI) — The International Chess Federation announced yesterday that technical details have been settled for the world championship match between Boris Spassky of the Soviet Union and challenger Bobby Fischer of the United States.

The agreement was worked out in weekend negotiations among representatives of the chess federations of the Soviet Union, the United States, Yugoslavia and Iceland, and personal representatives of the two players, the announcement said.

The federation said the rules agreed on were:

The match will consist of a maximum of 24 games.

Spassky, as defending champion, must score 12 match points to retain the title. Fischer must score 12.5 points to win. Whoever reaches the assigned total first is the victor.

Total prize money will be $138,500, of which the winner receives 62.5 per cent and the loser 37.5 per cent. In case of a 12-12 final result, each player receives $69,250.

The first 12 games will be played in the Yugoslavian capital of Belgrade, the opening match being scheduled for June 22. The next day is reserved for continuing ad adjourned game. The second half of the tournament will be played in Reykjavik, Iceland.

Games will be played on Sundays, Tuesdays and Thursdays. Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays are reserved for continuing adjourned games. There will be no play on Saturdays.

The Lowell Sun Lowell, Massachusetts Wednesday, March 22, 1972 - Page 66

Chess Challengers Spar

Sydney (Reuter)—World champion chess player Boris Spassky of Russia and his American challenger Bobby Fischer are limbering up for their scheduled clash like a couple of heavyweight boxers, according to a top official.

For Mr. Spassky, training includes road work and weight lifting. Prof. Max Euwe, president of the World Chess Federation, told reporters.

For Mr. Fischer, it means eating mountainous quantities of steak and drinking plenty of apple juice, said Dr. Euwe.

Apart from tucking into the steak and apple juice, 28-year-old Mr. Fischer is training in a tomb-like existence with his chessboard.

It is still not certain, however, where or when the “chess tournament of the century” will take place. Mr. Fischer, who has been called the Muhammad Ali of the chessboard, refused to play Mr. Spassky in Russia.

So Dr. Euwe, as president of the federation, decided that six of the 12 games would be played in Yugoslavia and six in Iceland.

Mr. Fischer agreed, but this time Mr. Spassky said no.

Dr. Euwe, a Dutchman who was world chess champion from 1935-37, says he has made his decision on the locations for the tournament and that is the rule. Mr. Spassky will lose his title by default if he does not play, he says.

As for their training methods, Professor Euwe says: “I preferred cold showers and tennis to prepare for the big games.”

The Morning Record Meriden, Connecticut Wednesday, March 22, 1972 - Page 6

Another World Series

There won't be any cheering from the stands, there won't be any hot dogs or beer sold, but the interest of the spectators and followers around the world will be no less fervid when the world series of chess opens later this year.

The series of 24 games will be played in two European cities, Belgrade, Yugoslavia, and Reykjavik, Iceland, starting June 22 in Belgrade.

The contestants will be Bobby Fischer of the United States and Boris Spassky of the Soviet Union, the defending world champion. There is $138,500 in prize money involved. The winner will take 72½ per center; the loser the remainder. If the match ends in a 12-12 tie, Spassky will keep the title; the money will be divided equally.

Three games will be played weekly, the last Belgrade match is scheduled for July 18. If the match goes the full 24 games, the last game will be played Aug. 41 in Iceland's capital.

Chess is the most complex and profound competitive intellectual exercise, calling for analytical ability, memory, imagination, boldness in offense, resourcefulness in defense. The origins of chess are lost in obscurity. The game has developed over the centuries in many lands, increasing in complexity. So-called modern chess began about the 15th Century, first in France and then in Spain. The English school of chess dates from the 19th Century. Among the modern chess masters have been Lasker, a German; Capablanca, a Cuban; and Alekhine, a Russian. Chess is a popular sport in the Soviet Union, playing by young and old alike, not only in homes and at chess clubs, but in parks and playgrounds.

For the most part, Americans have not distinguished themselves in chess. There have been two exceptions, however: one is Bobby Fischer, the present challenger, who lives, eats, breathes, and sleeps chess. The other was another young man, Paul Morphy (1837-1884), who was taught chess by his father at the age of 10. His brilliance in international competition has scarcely been equalled, and while his career was short, it was meteoric.

The fact that the United States now has another player of world championship caliber for the first time in more than a century is cause for national pride. Bobby Fischer's performance at Belgrade and Reykjavik will be watch with intense interest by chess fans throughout the entire world.

The Evening Sun Baltimore, Maryland Friday, March 24, 1972 - Page 4

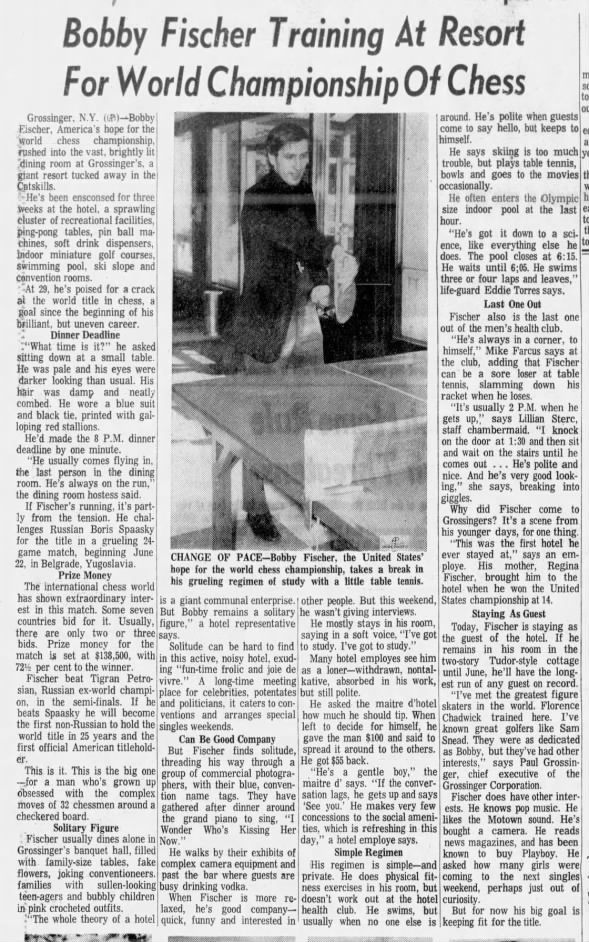

Bobby Fischer Training At Resort For World Championship of Chess by Ann Hencken

Grossinger, N.Y. (AP) — Bobby Fischer, America's hope for the world chess championship, rushed into the vast, brightly lit dining room at Grossinger's, a giant resort tucked away in the Catskills.

He's been ensconced for weeks at the hotel, a sprawling cluster of recreational facilities, Ping Pong tables, pin ball machines, Pepsi dispensers, indoor miniature golf courses, swimming pool, ski slope and convention rooms.

At age 29, he's poised for a crack at the world title in chess, a goal since the beginning of his brilliant, but uneven, career.

Dinner Deadline

“What time is it?” he asked sitting down at a small table. He was pale and his eyes were darker looking than usual. His hair was damp and neatly combed. He wore a blue suit and black tie, printed with galloping red stallions.

He'd made the 8 p.m. dinner deadline by one minute.

“He usually comes flying in, the last person in the dining room. He's always on the run,” said the dining room hostess.

If Fischer's running, it's partly from the tension. He challenges Russian Boris Spassky for the title in a grueling 24-game match, beginning June 22, in Belgrade, Yugoslavia.

Prize Money

The international chess world has shown extraordinary interest in this match. Some seven countries bid for it. Usually, there are only two or three bids. Prize money for the match is set at $138,500, with 72½ per cent to the winner.

Fischer beat Tigran Petrosian, Russian ex-world champion, in the semifinals. If he beats Spassky he will become the first non-Russian to hold the world title in 25 years and the first official American title holder.

This is it. This is the big one—for a man who's grown up obsessed with the complex moves of 32 chessmen around a checkered board.

Solitary Figure

Fischer usually dines alone in Grossinger's banquet hall, filled with family-size tables, fake flowers, joking conventioneers, families with sullen-looking teen-agers and bubbly children in pink crocheted outfits.

“The whole theory of a hotel is a giant communal enterprise. But Bobby remains a solitary figure,” says a hotel representative. Solitude can be hard to find in this active, noisy hotel, exuding “fun-time frolic and joie de vivre.” A long-time meeting place for celebrities, potentates and politicians, it caters to conventions and arranges special singles weekends.

Can Be Good Company

But Fischer finds solitude, threading his way through a group of commercial photographers, with their blue, convention name tags. They have gathered after dinner around the grand piano to sing, “I Wonder Who's Kissing Her Now.” He walks by their exhibits of complex camera equipment and past the bar where guests are busy drinking Russian vodka.

When Fischer is more relaxed, he's good company— quick, funny and interested in other people. But this weekend, he wasn't giving interviews.

He mostly stays in his room, saying in a soft voice, “I've got to study. I've got to study.”

Many hotel employees see him as a loner—withdrawn, nontalkative, absorbed in his work, but still polite.

He asked the maitre d'hotel how much he should tip. When left to decide for himself, he gave the man $100 and said to spread it around to the others. He got $55 back.

“He's a gentle boy,” says the maitre d'.

“If the conversation lags, he gets up and says ‘See ya.’ He makes very few concessions to the social amenities, which is refreshing in this day,” says a hotel employee.

Simple Regimen

His regimen is simple—and private. He does physical fitness exercises in his room, but doesn't work out at the hotel health club. He swims—but usually when no one else is around. He's polite when guests come to say hello—but keeps to himself.

He says skiing is too much trouble, but he plays table tennis, bowls and goes to the movies occasionally.

He often enters the Olympic size indoor pool at the last hour.

“He's got it down to a science, like everything else he does. The pool closes at 6:15. He waits until 6:05. He swims three or four laps and leaves,” says life guard Eddie Torres.

Last One Out

Fischer also is the last one out of the men's health club.

“He's always in a corner, to himself,” says Mike Farcus at the club, adding that Fischer can be a sore loser at table tennis, slamming down his racket when he loses.

“It's usually 2 p.m. when he gets up.” says Lillian Sterc, staff chambermaid. “I knock on the door at 1:30 and then sit and wait on the stairs until he comes out…He's polite and nice. And he's very good looking,” she says, breaking into giggles.

Why did Fischer come to Grossinger's? It's a scene from his younger days, for one thing.

“‘This was the first hotel he ever stayed at,” says an employee. His mother, Regina Fischer, brought him to the hotel when he won the U.S. championship at age 14.

Staying As Guest

Today, Fischer is staying as the guest of the hotel. If he remains in his room in the two-story Tudor-style cottage until June, he'll have the longest run of any guest on record.

“I've met the greatest figure skaters in the world. Florence Chadwick trained here. I've known great golfers like Sam Snead. They were as dedicated as Bobby but they've had other interests,” says Paul Grossinger, chief executive of the Grossinger Corp.

Fischer does have other interests. He knows pop music. He likes the Motown sound. He's bought a camera. He reads news magazines. He asked how many girls were coming to the next singles weekend, perhaps just out of curiosity.

But for now his big goal is keeping fit for the title.

Bobby Fischer Training At Resort For World Championship of Chess Fri, Mar 24, 1972 – 4 · The Evening Sun (Baltimore, Maryland) · Newspapers.com

Bobby Fischer Training At Resort For World Championship of Chess Fri, Mar 24, 1972 – 4 · The Evening Sun (Baltimore, Maryland) · Newspapers.com

The Herald-News Passaic, New Jersey Friday, March 24, 1972 - Page 8

Fischer Checked in Money Appeal

Belgrade (AP) — Organizers of the Fischer-Spassky championship chess match followed the lead of their colleagues in Iceland yesterday and turned down a request by Bobby Fischer for a change in financial conditions.

The U.S. champ had asked in a cable last week to the Icelandic organizers that all money left over after the cost of the match was covered should be split between him and Soviet champion Boris Spassky.

This followed reports from Amsterdam last week that agreement had been reached on financial matters between representatives of the players and organizers.

The Amsterdam agreement followed months of negotiations on a site for the match, finally settled recently when Dr. Max Euwe, president of the International Chess Federation, announced it would play half in Belgrade and half in Reykjavik, Iceland.

The Icelandic organizers quickly refused Fischer's request to change the financial arrangements. The Yugoslavian organizers cabled the chess federations of Iceland, the Soviet Union and the United States and Dr. Euwe, saying they would not accept any change. They added that the organizers, bearing the financial risk, were entitled to any profits that ensued.

New York Times, New York, New York, Sunday, March 26, 1972 - Page 33

Fischer Reported Quitting an Accord On Site for Match

Reykjavik, Iceland, March 25 (AP) — Bobby Fischer was reported today to have withdrawn from an earlier agreement to play the second half of his world title chess match here with the Soviet Union's Boris Spassky the current champion.

Gudmunder G. Thorarinsson, president of the local chess association, said that Mr. Fischer's refusal would now require attention by the International Chess Federation, which originally handled the delicate negotiations that led to the selection of Reykjavik as the site for the second half of the match.

The first 12 games between Mr. Fischer and Mr. Spassky are scheduled to begin June 22 in Belgrade, Yugoslavia. It was not immediately clear whether these would begin on schedule. Under International Chess Federation rules, the match must begin by July 1.

The second half of the world match, which could last another 12 games, was supposed to begin here August 6.

The reasons for Mr. Fischer's decisions were reportedly financial. The 28-year-old native New Yorker was said to have requested a change in financial conditions for the match but was turned down by both Reykjavik and Belgrade.

The conditions agreed upon last month were that the prize money of $138,000 offered by the two cities would be split, with 62.5 per cent for the winner and 37.5 per center for the loser. This was a compromise settlement — Mr. Fischer had favored holding the entire match in Belgrade, which had offered $152,000, and Mr. Spassky had wanted Reykjavik, which had offered $125,000.

Mr. Fischer's request reportedly was that all profits from the match be divided between himself and Mr. Spassky. But organizers argued that, since they bore a financial risk, they were entitled to the profits.

— NYTimes—Bobby Fischer was unavailable for comment at Grossinger's, in Monticello, N.Y., where he was appearing in an exhibition match. Edmund Edmondson, executive director or the United States Chess Federation, was also unavailable for comment.

The Times Herald Port Huron, Michigan Sunday, March 26, 1972 - Page 8

Fischer Refuses Chess Title Game

Reykjavik, Iceland (AP) — U.S. chess wizard Bobby Fischer has informed local officials he will not play the second half of his world title match against the Soviet Union's Boris Spassky in Iceland, the president of the local chess association said Saturday.

Gudmundur G. Thorarinsson said the International Chess Federation should tackle the problem.

Fischer has requested a change in financial conditions for the match and was turned down by both Reykjavik and Belgrade, Yugoslavia. The two cities have been named as sites for the match.

In a second telegram to Iceland Friday, Fischer said that because of “unacceptable financial terms” he refused to play Iceland at all.

Fischer had asked in a cable to the Icelandic organizers that all money left over after the cost of the match should be divided between Spassky and himself.

The organizers in Belgrade on Thursday followed the lead of their colleagues in Reykjavik by refusing altered financial conditions.

These developments followed reports from Amsterdam that an agreement on financial matters had been reached by representatives of the players and the organizers.

The Yugoslav organizers on Thursday cabled the chess federations of Iceland, the Soviet Union and the United States, and Dr. Max Euwe, president of the international organization, saying they would not accept any change.

They said that the organizers, bearing the financial risk, were entitled to any profits that ensued.

In Amsterdam, top officials of the International Chess Federation —FIDE— conferred on Fischer's refusal to play in Iceland.

Secretary Henrik Slavenkoorde of the Netherlands said he could not comment on FIDE's future plans but added that he was in contact with the federation's deputy president Rabell Mendez, in San Juan, Puerto Rico. President Euwe is traveling abroad.

Mendez chaired the Amsterdam meeting last weekend in which Ed Edmondson represented Fischer in signing an agreement covering all financial details of the match, a FIDE spokesman said.

New York Times, New York, New York, Sunday, March 26, 1972 - Page 210

Chess: Eleventh 'Chess Informant' Is Out by Al Horowitz

The eleventh number of the semi-annual Yugoslav “Chess Informant” (covering approximately the first six months of 1971) is now available in this country, but it is not, for a happy change, “even bigger than the last.” To be exact, Number Eleven contains 622 games, compared with 841 in Number Ten.

The “Chess Informant,” as most tournament players already know, publishes mostly games, in algebraic notation, and with light, wordless notes—mostly suggesting alternate lines of play, enclosed in square brackets to distinguish them from the text of the game itself—but also an occasional cross-reference to games in previous issues with the same opening variation.

Other materials in each volume include crosstables of the events from which the games are taken, a “combinations” section, in which the reader is given various diagramed positions and asked to find the winning move in each (see the Quiz, below), news from the International Chess Federation, in any one of a number of languages, and so on. The 11th “Informant,” as well as many of the previous issues, is available from the United States Chess Federation, 470 Broadway, Newburgh, N.Y. 12550, at $6.50.

The “Informant” is, of course, primarily dedicated to inclusiveness, but the editors also run in each issue the results of a poll to select the 10 best games published in the previous issue. the 10 judges, including International Federation President and former world champion Dr. Max Euwe, grandmasters Dr. Petar Trifunovich of Yugoslavia, Alexander Kotov of the Soviet Union and others, each pick out 10 games and list them in order of preference. Then the results are tabulated — for every first-place vote it receives, a game is awarded 10 points, for each second-place vote, nine points, and so on.

Voted the best game from “Informant 10,” with a total of 52 points, was Danish grandmaster Bent Larsen's victory over Bobby Fischer from the 1970 Interzonal at Palma de Mallorca—the last game Fischer lost before he went off on his amazing winning streak. Second place (with 47) went to Fischer's win against Argentinean grandmaster Oscar Panno from the international tournament at Buenos Aires in 1970, and third place (with 46) to his win against Sam Schweber of Argentina in the same event.

In all, Fischer had five games on the list, three wins and two losses: his defeat at the hands of world champion Boris Spassky at the last Olympiad placed fifth, and his win over Vassily Smyslov of the Soviet Union at Palma, ninth.

Larsen's win over Fischer received mention by nine of the ten judges but only one first-place vote. Fischer's victory over Panno, on the other hand, was cited by only seven judges, but received three first-place votes, which goes to demonstrate, if further demonstration were needed, that excellence in chess is very must a matter of taste. The three top games are included here so that the reader may judge for himself.

The Sydney Morning Herald Sydney, New South Wales, Australia Sunday, March 26, 1972 - Page 81

Chess: One Against 25 by David D. McNicoll

The Atmosphere in Farmer's Blaxland Gallery is very tense. […] “…In June he will be traveling to Yugoslavia for the first session of the world championship series between Bobby Fischer of American and the titleholder Boris Spassky of Russia.

Late this week he was notified that both players had accepted his ruling that 12 games should be played in Yugoslavia and 12 in Iceland.

When he finished his 25 simultaneous games at Farmer's on Friday, the Professor's manner changed.

The look of intense concentration that had creased his brow faded and he stood erect and smiled for the first time.

“I don't know who will win the championship,” he said.

“Fischer will be in top form but I am not sure about Spassky.

“If he is at his best then it will be a very strong and close match.”

Professor Euwe said government sponsorship was the reason for the Russian domination of chess since he lost his world title in 1937.

He said that an aspiring world champion would have to devote his life to the game.

“But if you had only to play all the time you would get very bored,” he said.

As one of the world's leading experts on computer chess, Professor Euwe spent several years programming a computer to play but he believes that men will always be able to beat machines.

“A computer, unlike a man, has no creativity,” he said. “You can tell a computer all the moves and all the rules but you can still beat it because it cannot see the exceptions to the rules that chess allows.

Chess: One Against 25 Sun, Mar 26, 1972 – Page 81 · The Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney, New South Wales, Australia) · Newspapers.com

Chess: One Against 25 Sun, Mar 26, 1972 – Page 81 · The Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney, New South Wales, Australia) · Newspapers.com

The Signal Santa Clarita, California Monday, March 27, 1972 - Page 2

Those Americans

Yugoslav chess Grand Master Svetozar Gligoric (his friends call him Gligor) played 26 simultaneous games in Los Angeles last week. He galloped from board to board, pushing pawns and skipping knights. he lost one, won 23. The other two boards were played by ladies, and Gligoric, whose inclination is to chivalry and not Women's Lib, offered them both a draw.

Gligoric, former resistance fighter and a journalist when he's away from the boards, had dinner with local chess fans in Val Val.

He said that this (his fifth) tour of the U.S., is more strenuous than most because everyone's after him for June hotel reservations in his home town of Belgrade. June in Belgrade will see the Chess Match of the Century, with the Soviets' Boris Spassky meeting the U.S.'s Bobby Fischer.

Gligoric winds up his current tour in Houston, Texas, where a tournament will have an imposing list of players and prizes (top $4000). But Gligoric doesn't like to talk about Houston. The tournament is sponsored by an outfit called Church's Fried Chicken, a private-enterprise promotion quite foreign to his Communist homeland. “I'd never be able to explain that in Yugoslavia,” he sighed. “They wouldn't understand what a church has to do with a chicken — or what either have to do with chess.

Those Americans Mon, Mar 27, 1972 – 2 · The Signal (Santa Clarita, California) · Newspapers.com

Those Americans Mon, Mar 27, 1972 – 2 · The Signal (Santa Clarita, California) · Newspapers.com

The Sacramento Bee Sacramento, California Wednesday, March 29, 1972 - Page 33

U.S. Chess Champ Rejects Belgrade For Title Play

Belgrade (AP) — American chess wizard Bobby Fischer rejected Belgrade yesterday as one of the two sites in which he is willing to meet the Soviet Union's Boris Spassky for the world chess championship.

The Yugoslav organizers said they received a telegram from the challenger saying he no longer intended to play in Belgrade.

The Yugoslav capital and Reykjavik, Iceland were selected by the International Chess Federation—FIDE—as locations for the two-city match after months of negotiations.

Earlier this week, the organizers in Reykjavik said they had received a telegram from Fischer asking a share of the profits from the part of the match to be played in Iceland.

Fischer also wanted a share in the profits from the Belgrade match. The organizers in both capitals, who have been in constant touch, rejected his request.

The Yugoslavs, who offered the highest purse of $152,000, send a telegram to FIDE demanding a guarantee from Fischer that he will abide by the federation's original decision.

If Fischer is not willing to provide a guarantee, the Belgrade organizers said they will have to reconsider the plans to host the first half of the match—scheduled to take place June 22-July 19.

They apparently believe Fischer's telegrams are part of a campaign to gain more publicity and a bigger purse for the match.

The Central New Jersey Home News New Brunswick, New Jersey Thursday, March 30, 1972 - Page 30

They Just Want The Check, Mates

The one-time “enfant terrible” of chess, Bobby Fischer, has replaced temper tantrums with dollar deliriums. But for one raised in capitalist United States, that's not strange.

Fischer, who admits he moves pawns these days only for money, is seeking the most profitable deal he can get to meet the Soviet Union's Boris Spassky for the world title.

The plan was to split the matches between Iceland and Yugoslavia. All was going well, when Fischer decided he wanted more. What he wanted was for Spassky and himself to split all the money left after the cost of the matches.

Both Iceland and Yugoslavia said no. The Communist Yugoslavia representatives argued that the organizers, bearing the financial risk, were entitled to any profits that ensued.

Comrades, you sound like a pack of capitalist dogs.

Lincoln Journal Star Lincoln, Nebraska Friday, March 31, 1972 - Page 3

Belgrade Won't Set Up Chess Match

Belgrade, Yugoslavia (AP) — The Belgrade organizers of the Spassky-Fischer world chess match announced Friday they are dropping plans to organize the match in the scheduled period in this city.

The contract between world champion Boris Spassky of the Soviet Union and American challenger Bobby Fischer was set to start June 22. The second half of the 24-game match was to be played in Reykjavik, Iceland, under a compromise agreement reached in Amsterdam by the International Chess Federation (FIDE) and the two players.

The Belgrade decision was expected after the organizers received no pledge from the world federation that it would honor the Amsterdam agreement. Belgrade chess officials set a March 31 deadline for a reply.

On Thursday Fischer dismissed E.B. Edmondson, head of the U.S. Chess Federation, as his financial negotiator for the match and Edmondson said Fischer planned to conduct his own bargaining.

A Belgrade newspaper reported that Fischer had rejected a settlement Edmondson reached in Amsterdam for the players' share of the match. The agreement reportedly would have given the winner 72% of the $138,000 purse, with the rest going to the loser.

The Belgrade and Reykjavik organizers of the match turned down Fischer's requests for a change in financial conditions of the Amsterdam pact earlier in March. He had asked that all money left over after the cost of the match was covered should be split between him and Spassky. The organizers said they bore a financial risk and should have the right to profit.

In informing the world federation of their decision not to organize the match in June, the Belgrade group said in an telegram: “No Guarantee”

“Since Grandmaster Fischer had refused to play the match in Belgrade … also denying Edmondson the right to represent him, it is our appraisal that the agreement offers no guarantee to the organizers that the match will actually take place in the period agreed upon.”

The Belgrade paper had also claimed Thursday that Edmondson told an editor Fischer may have change his mind about meeting Spassky for the match. Edmondson denied the report.

The telegram from the Belgrade organizers said that, because of the lack of the guarantee, “we are not in the position to bear any further risk about organizing the match.”

Asbury Park Press Asbury Park, New Jersey Friday, March 31, 1972 - Page 18

Fischer Seen Still Set to Play Match

New York (AP) — E.B. Edmondson, head of the U.S. Chess Federation, who has been negotiating arrangements for Bobby Fischer's world championship match with Boris Spassky, said yesterday Fischer had informed him that he would conduct his own negotiations.

Edmondson denied, however, that he expressed any opinion that Fischer may have changed his mind about meeting Spassky, the Russian world champion.

A Belgrade newspaper reported earlier yesterday that Fischer had repudiated an agreement Edmondson reached for the players' share of the 24-game match to be played in Belgrade and Reykjavik, Iceland. The newspaper said the agreement would have given the winner of the match 72 per cent of the $138,000 purse, with the rest going to the loser.

The newspaper, the Daily Politika, also said its editor had been told by Edmondson by telephone that Edmondson believed Fischer had no intention of playing Spassky for the title.

Edmondson denied the latter report, saying it was completely false.

As for the repudiation of the agreement Edmondson said he could not comment on the report because since receiving a cable Monday from Fischer taking the negotiations out of his hands, he has had no contact with Fischer and “since then I haven't been involved.”

“As far as I'm concerned,” Edmondson said, “I hope the match still comes off between Fischer and Spassky.”

Fischer declined to comment on the reports.