New York Times, New York, New York, Wednesday, July 19, 1972 - Page 45

Spassky Plays to a Draw With Fischer in 4th Game by Harold C. Schonberg

Reykjavik, Iceland, July 18—After a nerve-racking, wearisome five-hour session of play this evening, Boris Spassky and Bobby Fischer drew the fourth game of the world's chess championship match.

After 45 moves, both players looked at each other, there was a tacit understanding and Fischer offered his hand, which Spassky took.

The score now stands at 2½ to 1½ in favor of the Russian.

The game was an exciting one, with dynamite on both sides. Early in the opening, a Sicilian Defense that Spassky set up against Fischer's inevitable first move, P-K4, Spassky sacrificed a pawn for the sake of a possible attack.

From then on, Spassky pressed that attack, with his two bishops pointing like twin daggers at Fischer's king. Fischer was forced on the defense to maintain his one-pawn majority, and at one point was in danger of being mated.

Precise Play Demanded

The game demanded precise, concentrated play. Spassky took about a half hour for his 18th move, and even more than that for his 19th. The game was by far the most complicated of the three the champion and his American challenger have played so far. Professionals in the audience could hardly keep up with the possibilities.

However, a Yugoslav grandmaster, Svetozar Gligoric said that Spassky's 29th move, R-KR1, was in error. Had he not erred, Gligoric said, Spassky would have had a clear victory. The Yugoslav did not say what the winning move should have been.

After an exchange of rooks on the 39th move, there was no doubt about the outcome. With the same number of pawns on each side, and with bishops of opposite colors, the result was a textbook draw.

Some had come to the same conclusion several moves before the end. The three Russians of Spassky's entourage—Efim Geller and Nikolai Krogius, grandmasters, and an international master, Ivo Nei—were seen leaving the hall a good 10 minutes before the end of the game. They knew.

Cameras Are Removed

The game, held on the stage of Exhibition Hall, was preceded by the skirmishing that has been the way of life of this match. This time neither player arrived at 5 P.M.

The referee, Lothar Schmid, started Fischer's clock promptly at 5. Spassky reached the stage seven minutes later. Fischer was 10 minutes late. He had been on the second floor making sure that film and television cameras had been removed from the hall.

The cameras were there only 20 minutes before game time. The film crew of Chester Fox, Inc., had installed them. Mr. Fox has made an exclusive contract with the Icelandic Chess Federation for all film rights.

“I put the cameras in every day,” said Mr. Fox. “That's what my contract reads. And they are ordered out every day, because Fischer threatens to leave.”

Fischer and the 35-year-old titleholder, like most grandmasters, demand a tomb-like silence when they play. Fischer has been known to object to whispers in the playing room. At one point during the play today, the match organizers ordered the hinges on the doors oiled because a squeak was heard.

The game was described as absorbing and exciting by experts, and an audience of some 1,200 seems to agree, “What a great game!” was heard from every side.

The Sicilian Defense is one of the oldest openings known to chess. Characterized by the move … P-QB4, it leads to exciting tilts, with the black pieces highly mobile and poised for counterattack. The opening gets its name from a 17th-century Sicilian player, Gioacchino Greco, who specialized in it. In recent years it has become one of the most popular answers to the king's pawn opening, which is Fischer's specialty.

Spassky Comes Prepared

Spassky and Fischer are, of course, thoroughly familiar with the Sicilian Defense. Fischer is generally regarded as the world's greatest living expert in it, and Spassky has scored notable victories in the Sicilian.

The champion came to this game fully prepared for Fischer's inevitable opening move, and his offer of a pawn early in the game, while not unusual, had clearly been intensively analyzed by Spassky and his team.

Of the three games played so far—Fischer lost the second on a forfeit—it has been the player of the black pieces who has carried the attack. This is rather unusual. Generally, white comes out swinging and maintains the pressure.

The next game is scheduled to start at 5 P.M. (1 P.M. New York Time) Thursday. Meetings, meanwhile, will continue in an effort to solve the camera impasse. The Russians so far have not entered into the dispute, though today it was reported that they had indicated a desire to have all games on film for the Soviet audience.

The Evening Sun Baltimore, Maryland Wednesday, July 19, 1972 - Page 3

Chess Kings Tie In Fourth Game

Ready For Battle—Bobby Fischer, U.S. chess player, arrives at hall in Reykjavik, Iceland. The fifth match in the 24-game series will take place Thursday.

Reykjavik, Iceland (AP)— Boris Spassky was stony-faced and Bobby Fischer smiled and waved after their fourth game in the world chess championship ended in a draw Tuesday night.

The standoff came after 5 hours of what many in the crowd of about 1,200 felt was the most exciting match thus far.

At the 45th move Fischer extended his hand to Spassky and the Russian accepted.

With each player picking up half a point on the draw, the score is 2½-1½ in the Russian's favor. The fifth match in the 24-game series is Thursday at 1 P.M.

Sozin Attack

Fischer had the white pieces Tuesday and with them the first move and led off with his favorite Sozin attack, p-K4.

The Russian pulled a surprise by counter-attacking aggressively and sacrificing a pawn to open up useful lines of attack.

“Spassky's got a lot of guts,” said U.S. grandmaster Robert Byrne. “He may be going for a win.”

After quickly making the first few moves, the two settled down to a dogged pace and the neon “silence” sign flashed repeatedly as the audience fidgeted.

The Vancouver Sun Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada Wednesday, July 19, 1972 - Page 38

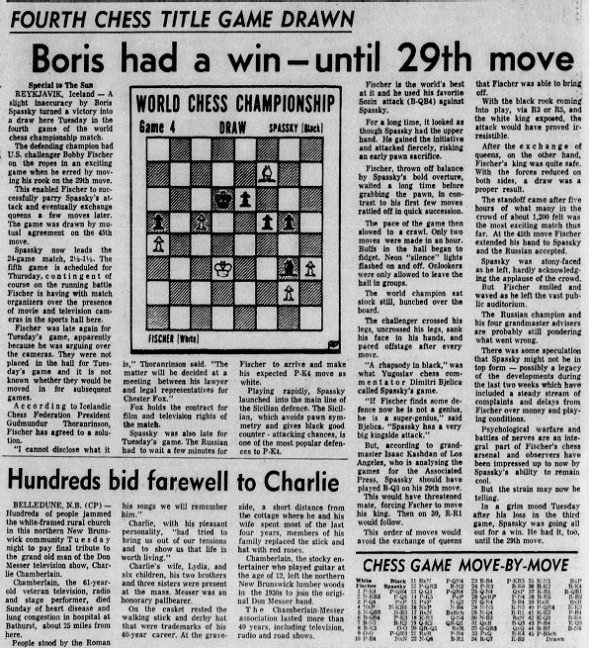

Fourth Chess Title Game Drawn: Boris Had A Win—Until 29th Move

Reykjavik, Iceland—A slight inaccuracy by Boris Spassky turned a victory into a draw here Tuesday in the fourth game of the world chess championship match.

The defending champion had U.S. challenger Bobby Fischer on the ropes in an exciting game when he erred by moving his rook on the 29th move.

This enabled Fischer to successfully parry Spassky's attack and eventually exchange queens a few moves later. The game was drawn by mutual agreement on the 45th move.

Spassky now leads the 24-game match, 2½-1½. The fifth game is scheduled for Thursday, contingent of course on the running battle Fischer is having with match organizers over the presence of ([disruptive crews of men operating]) move and television cameras in the sports hall here.

Fischer was late again for Tuesday's game, apparently because he was arguing over the cameras. They were not placed in the hall for Tuesday's game and it is not known whether they would be moved in for subsequent games.

According to Icelandic Chess Federation President Gudmundur Thorarinsson, Fischer has agreed to a solution.

“I cannot disclose what it is,” Thorarinsson said. “The matter will be decided at a meeting between his lawyer and legal representatives for Chester Fox.”

Fox holds the contract for film and television rights of the match.

Spassky was also late for Tuesday's game. The Russian had to wait a few minutes for Fischer to arrive and make his expected P-K4 move as white.

Playing rapidly, Spassky launched into the main line of the Sicilian defence. The Sicilian, which avoids pawn symmetry and gives black good counter-attacking chances, is one of the most popular defenses to P-K4.

Fischer is the world's best at it and he used his favorite Sozin attack (B-QB4) against Spassky.

For a long time, it looked as though Spassky had the upper hand. He gained the initiative and attacked fiercely, risking an early pawn sacrifice.

Fischer, thrown off balance by Spassky's bold overture, waited a long time before grabbing the pawn, in contrast to his first few moves rattled off in quick succession.

The pace of the game then slowed to a crawl. Only two moves were made in an hour. Buffs in the hall began to fidget. Neon “silence” lights flashed on and off. Onlookers were only allowed to leave the hall in groups.

The world champion sat stock still, hunched over the board.

The challenger crossed his legs, uncrossed his legs, sank his face in his hands, and paced offstage after every move.

“A rhapsody in black,” was what Yugoslav chess commentator Dimitri Bjelica called Spassky's game.

“If Fischer finds some defence now he is not a genius, he is a super-genius,” said Bjelica. “Spassky has a very big kingside attack.”

But, according to grandmaster Isaac Kashdan of Los Angeles, who is analyzing the games for the Associated Press, Spassky should have played B-Q3 on his 29th move.

This would have threatened mate, forcing Fischer to move his king. Then on 30, R-R1 would follow.

This order of moves would avoid the exchange of queens that Fischer was able to bring off.

With the black rook coming into play, via R3 or R5, and the white king exposed, the attack would have proved irresistible.

After the exchange of queens, on the other hand, Fischer's king was quite safe. With the forces reduced on both sides, a draw was a proper result.

The standoff came after five hours of what many in the crowd of about 1,200 felt was the most exciting match thus far. At the 45th move Fischer extended his hand to Spassky and the Russian accepted.

Spassky was stony-faced as he left, hardly acknowledging the applause of the crowd.

But Fischer smiled and waved as he left the vast public auditorium.

The Russian champion and his four grandmaster advisers are probably still pondering what went wrong.

There was some speculation that Spassky might not be in top form — possibly a legacy of the developments during the last two weeks which have included a steady stream of complaints and delays from Fischer ([and the European organizers, and the Soviet organizers in collusion with Chester Fox, Inc doing everything possible to wreck the match]) over money and playing conditions. ([Actually, in an August 8, 1985 interview with Boris Spassky, the report states: “Many observers thought Fischer's furor sapped Spassky's concentration, but Spassky says the job was done by Moscow. More seriously, he says Fischer was the stronger player at that point in their careers, but “I could have resisted better.”])

Psychological warfare and battles of nerves are an integral part of ([the Soviet]) chess arsenal ([which Fischer is forced to spend his time dodging. Just as Fischer was quoted as saying, “I don't believe in psychology. I believe in good moves.”]) and observers have been impressed up to now by Spassky's ability to remain cool.

But the strain may now be telling.

In a grim mood Tuesday after his loss in the third game, Spassky was going all out for a win. He had it, too, until the 29th move.

Boris Had a Win -- Until 29th Move 19 Jul 1972, Wed The Vancouver Sun (Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada) Newspapers.com

Boris Had a Win -- Until 29th Move 19 Jul 1972, Wed The Vancouver Sun (Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada) Newspapers.com

The Baltimore Sun Baltimore, Maryland Wednesday, July 19, 1972 - Page 2

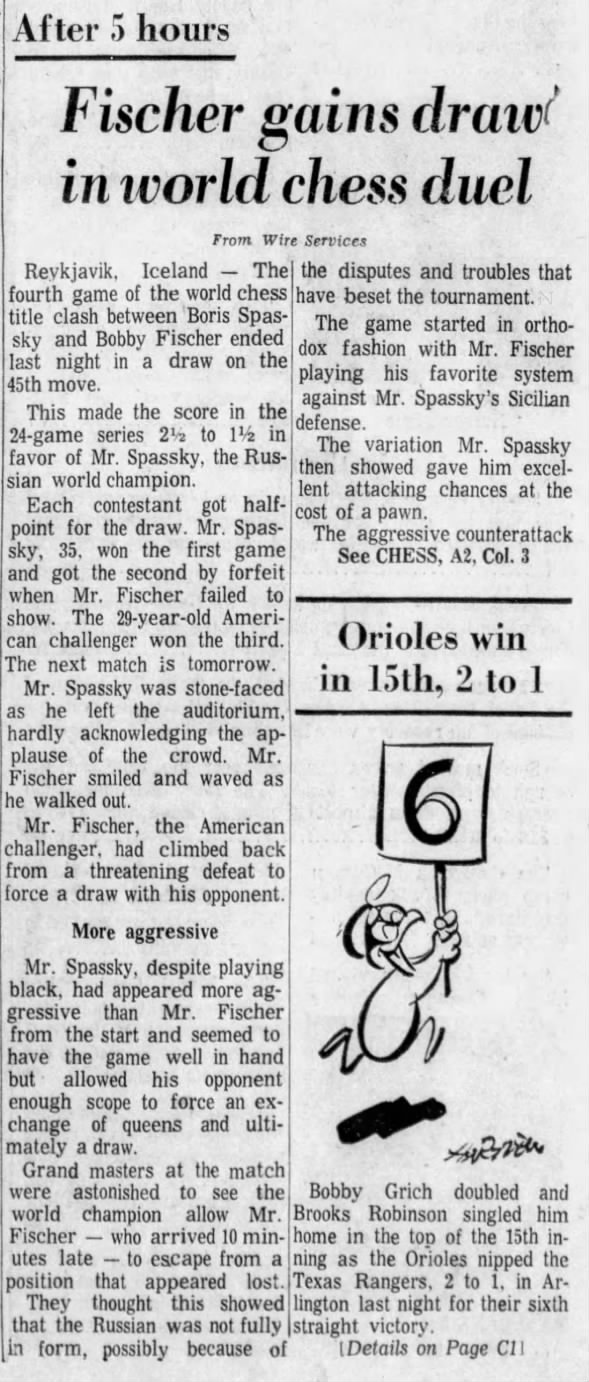

After 5 Hours: Fischer Gains Draw in World Chess Duel

Reykjavik, Iceland — The fourth game of the world chess title clash between Boris Spassky and Bobby Fischer ended last night in a draw on the 45th move.

This made the score in the 24-game series 2½ to 1½ in favor of Mr. Spassky, the Russian world champion.

Each contestant got half-point for the draw. Mr. Spassky, 35, won the first game and got the second by forfeit when Mr. Fischer failed to show. The 29-year-old American challenger won the third. The next match is tomorrow.

Mr. Spassky was stone-faced as he left the auditorium, hardly acknowledging the applause of the crowd. Mr. Fischer smiled and waved as he walked out.

Mr. Fischer, the American challenger, had climbed back from a threatening defeat to force a draw with his opponent.

More Aggressive

Mr. Spassky, despite playing black, had appeared more aggressive that Mr. Fischer from the start and seemed to have the game well in hand but allowed his opponent enough scope to force an exchange of queens and ultimately a draw.

Grand masters at the match were astonished to see the world champion allow Mr. Fischer — who arrived 10 minutes late — to escape from a position that appeared lost.

They though this showed that the Russian was not fully in form, possibly because of the disputes and troubles that have beset the tournament.

The game started in orthodox fashion with Mr. Fischer playing his favorite system against Mr. Spassky's Sicilian defense.

The variation Mr. Spassky then showed game him excellent attacking chances at the cost of a pawn.

The aggressive counterattack by Mr. Spassky clearly surprised Mr. Fischer.

Visiting grand masters called it a courageous move on the Russian's part, and an American grand master, Robert Byrne said: “Spassky's got guts. He may be going for a win.”

Mr. Spassky needs only 12 points to retain his title. Mr. Fischer must score 12½ to take the championship out of the Soviet Union, where it has reposed since 1948. A win counts one point and a draw half a point.

Mr. Fischer, who had made his first few moves in quick succession, waited a long time before taking Spassky's pawn. Then the pace of the game began to drag.

Experts said it was clear that Mr. Spassky had not really determined a firm course of strategy since he thought for more than 30 minutes over his 19th move.

Mr. Fischer defended well, but Mr. Spassky had obtained a situation which had to be regarded as a winning one, and after four hours of play, most bets were on the Russian.

“If Fischer finds some defense, he is not a genius, he is a supergenius,” said Dmitri Bjelica, a Yugoslav chess commentator.

“Fischer has almost lost,” said Dragoljub Janosevic, a Yugoslav grandmaster.

Then, in a turnabout, Mr. Fischer pinned Mr. Spassky's queen against his king, forcing a swap of queens. This terminated the Russian's mating attempt, leaving an end game of rooks and bishops of opposite colors.

The pace quickened. Mr. Spassky was running short of time because of his long deliberations earlier.

The experts began to say it looked like a draw. A few minutes later it was, by mutual agreement. The champion and challenger shook hands across the board. The audience gave them a standing ovation.

For the first time in the series, Mr. Spassky was late in arriving—but not so late as Mr. Fischer. The Soviet champion walked onstage four minutes after the clock started.

Fischer looked confident and relaxed, buoyed by his win Monday. It was the first time in his career Mr. Fischer had beaten Mr. Spassky. He lost to the Russian three times playing white in their five meetings before the world championship round began a week ago.

Fischer Gains Draw In World Chess Duel 19 Jul 1972, Wed The Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, Maryland) Newspapers.com

Fischer Gains Draw In World Chess Duel 19 Jul 1972, Wed The Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, Maryland) Newspapers.com

The Indianapolis Star Indianapolis, Indiana Wednesday, July 19, 1972 - Page 10

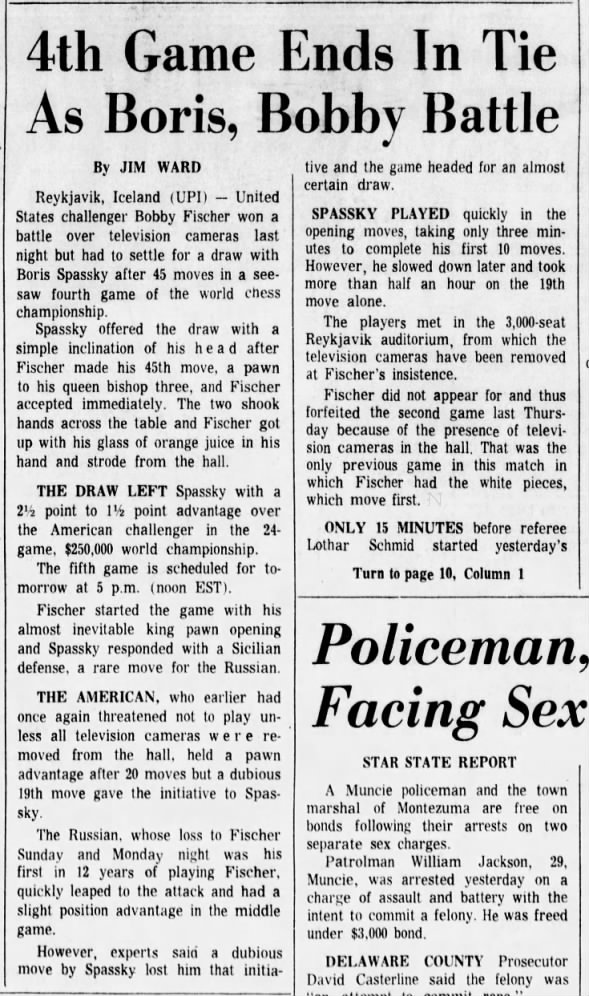

4th Game Ends In Tie As Boris, Bobby Battle by Jim Ward

Reykjavik, Iceland (UPI)—United States challenger Bobby Fischer won a battle over television cameras last night but had to settle for a draw with Boris Spassky after 45 moves in a see-saw fourth game of the world chess championship.

Spassky offered the draw with a simple inclination of his head after Fischer made his 45th move, a pawn to his queen bishop three, and Fischer accepted immediately. The two shook hands across the table and Fischer got up with his glass of orange juice in his hand and strode from the hall.

THE DRAW LEFT Spassky with a 2½ point to 1½ point advantage over the American challenger in the 24-game, $250,000 world championship.

The fifth game is scheduled for tomorrow at 5 p.m. (noon EST).

Fischer started the game with his almost inevitable king pawn opening and Spassky responded with a Sicilian defense, a rare move for the Russian.

THE AMERICAN, who earlier had once again threatened not to play unless all television cameras were removed from the hall, held a pawn advantage after 20 moves but a dubious 19th move gave the initiative to Spassky.

The Russian, whose loss to Fischer Sunday and Monday night was his first in 12 years of playing Fischer, quickly leaped to the attack and had a slight positional advantage in the middle game.

However, experts said a dubious move by Spassky lost him that initiative and the game headed for an almost certain draw.

SPASSKY PLAYED quickly in the opening moves, taking only three minutes to complete his first 10 moves. However, he slowed down later and took more than half an hour on the 19th move alone.

The players met in the 3,000-seat Reykjavik auditorium, from which the television cameras have been removed at Fischer's insistence.

Fischer did not appear for and thus forfeited the second game last Thursday because of the presence of ([audibly and visually disruptive men operating]) television cameras in the hall. That was the only previous game in this match in which Fischer had the white pieces, which move first.

ONLY 15 MINUTES before referee Lothar Schmid started yesterday's game at the scheduled time of 5 p.m., Chester Fox of New York, who has the film rights here, tried to reinstall the ([human-operated crews of large, bulky]) cameras. Fischer refused to play if the ([disruptive crews of men operating the]) cameras were allowed in the hall, however, and Fox agreed to remove them.

“There will be no play if the cameras are brought in, that is sure,” one Fischer aide told the Icelandic Chess Federation, organizers of the match.

NEITHER FISCHER nor Spassky was present when Schmid started the American's clock and the game. But Fischer showed up within four minutes and Spassky arrived a few minutes later.

Fischer immediately went to the board, looked at it briefly and move. His opening was hardly a surprise. In thousands of games Fischer has only varied from the king pawn opening a half dozen times or so.

Once asked why he always used the king pawn opening, Fischer said “Because it's the best move.”

AIDES TO THE American challenger said the reason for his tardiness yesterday was that Fischer had been eating an Icelandic special dish called skyr and saw no reason to gulp his food.

After the seventh move, the huge “silence” signs began flashing off an on in the hall to quiet a buzz of excitement created by Spassky's seventh move, bishop to king two. The Soviet champion left the stage after making it.

FISCHER STUDIED the board for a full seven minutes before moving a bishop to king three and leaning back in his special leather swivel chair. Spassky walked back onstage almost immediately and made his next move.

The two played quickly, Fischer completing his first 10 moves in 16 minutes. Spassky took only three minutes to complete his first 10 moves.

Spassky, apparently calm despite his first loss at a chess table in 12 years and his first ever to Fischer Monday, walked off an on the playing stage frequently.

THE DEMAND FOR silence in the hall was so urgent that at one point, while Fischer was studying a move, organizers sent young boys with oil cans to lubricate the doors leading into the hall to stop them from squeaking.

International masters watching the game said there had been no spectacular or unusual play through 12 moves. Fischer's lengthy study of moves did not indicate any trouble or indecisiveness but only that he was studying which of many variants to use against Spassky's defense.

SPASSKY RARELY employs a Sicilian defense, and international chess experts said his play was extremely fast even by grandmaster standards.

With one point awarded for each victory and a half point for a draw, Spassky needs 12 point to defeat Fischer and retain his championship in this match. As the challenger, Fischer needs 12½ points to win the match.

THE WINNER WILL receive $150,000 of the purse. The two players also were to share in 30 per cent of the television filming rights, but Fischer's refusal to play before the ([disruptive crews of men hired to operate the bulky and visually and audibly disruptive]) cameras after the first game left this financial arrangement in doubt ([and Fischer himself was upset that the match couldn't have been filmed, however, he was misled to believe stationary cameras that were automatic were to be installed and in use, after arrival to the first match, learned he had been misled by Soviet-Icelandic organizers and their co-conspirator Chester Fox, Inc.])

The two began the third game of the match Sunday in a small room off the auditorium but completed it Monday on the stage after the cameras had been removed from their original location points.

4th Game Ends In Tie As Boris, Bobby Battle 19 Jul 1972, Wed The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana) Newspapers.com

4th Game Ends In Tie As Boris, Bobby Battle 19 Jul 1972, Wed The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana) Newspapers.com

The Ottawa Journal Ottawa, Ontario, Canada Wednesday, July 19, 1972 - Page 6

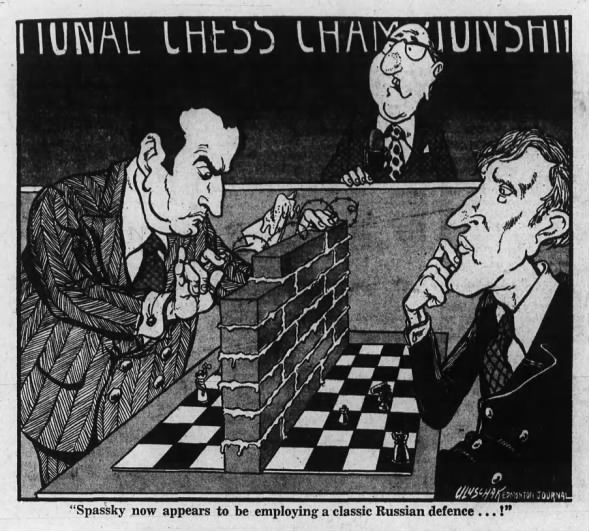

"Spassky Now Appears to Be Employing a Classic Russian Defence...!" 19 Jul 1972, Wed The Ottawa Journal (Ottawa, Ontario, Canada) Newspapers.com

"Spassky Now Appears to Be Employing a Classic Russian Defence...!" 19 Jul 1972, Wed The Ottawa Journal (Ottawa, Ontario, Canada) Newspapers.com

Spassky Now Appears to Be Employing a Classic Russian Defence...!

Chess No Longer Considered a Game for Slow-Moving Graybeards

Written for the Manchester Guardian and The Journal by Leonard Barden

Reykjavik. The world chess championship match between Bobby Fischer and Boris Spassky in Reykjavik marks a new high in public awareness of a game which has radically altered its old image of an introverted refuge for slow-moving graybeards.

The column inches written on Fischer's delay in turning up, on the tangled and acrimonious match negotiations (the International Chess Federation's finances “suffered very heavy blows” from the 139 telegrams sent out to Moscow, New York, Belgrade, and Reykjavik at a cost of nearly $2,400 between January and May this year), and on Fischer's heavyweight-style training (complete with 300 pound punch-bag, skipping rope, and underwater deep breathing exercises) have already given the contest more write-ups than all the other world championship matches put together.

Fischer, of course, is a journalistic gift with his stance as a Muhammad Ali cum George Best at one moment fighting the cold war single-handed and at another casually dismissing the champion's chances.

Fischer's justifiable distrust of the Russians dates back at least to the 1962 Candidates' tournament, where he accused his five Russian opponents of cheating by arranging routine draws ([which in recent years, expert consensus aside of former Soviet testimony to confirm Fischer's suspicion, statistical analysis has been provided to further confirm the Soviets were in fact, cheating. Guilty as charged.]) with each other while going full out against the non-Russians. ([Further evidence from Fischer's contemporaries such as Dr. Edward Lasker, president of the Association of American Chess Masters, publishing his own observations on the methods of unsportsmanlike conduct and Soviet cheating, as far back as 1950. There was nothing new about Fischer's allegations, and with valid basis to found such suspicions, including experts around the world who were even then in agreement: https://bfchos.blogspot.com/2018/07/soviet-grandmaster-draws-us-chess-and.html])

Later in 1962, Bobby claimed that the then world champion, Botvinnik, took advice from his team captain during the USA-USSR match. Nobody believed it, and even the captain of the U.S. team declined Bobby's request to lodge a protest. Botvinnik told me after this game that Fischer had only spoken three words to him in his life. Upon being introduced, Bobby said “Fischer!” before the game in 1962 they almost bumped heads when they sat down and Fischer said “Sorry!” and as the game ended Fischer said “Draw!” ([and in 1950: Dr. Edward Lasker, president of the Association of American Chess Masters, says of chess tournament play: “In communist countries the open practice of analyzing adjourned positions (that is, games on which a recess has been called) with others, unless adopted because somebody else is doing the same thing, seems to indicate a curious perversion of the most fundamental concept of sportsmanship by introducing the idea of mass cooperation into a contest between two individuals.” He goes on to cite an instance in which a Russian apparently got help from friends during a recess. No object lesson of current Russian practice is available because the Russians are not taking part in the Grand Masters' tournament being held now in Amsterdam. In a new book, “The Adventure of Chess,” to be published Wednesday by Doubleday, Dr. Lasker scorns the “increasing laxity of chess morals” generally. Another evidence of this, he says, is the habit of paired tournament players to agree to a draw if it doesn't affect their own standing, regardless of the effect of their action on other players. While world champion Mikhail Botvinnik of Russia unquestionably deserved his crown because of superiority in tournament play, says Dr. Lasker, the United States master Samuel Reshevsky might beat him in match play.” -Spokane Chronicle Spokane, Washington Tuesday, November 21, 1950; https://www.newspapers.com/clip/35016034/chess_cheating_charged_to_reds/])

BOBBY'S suspicion of Russians is still very live: when, in their match last year, Taimanov drew the envelope allotting him the white pieces in the first game. Fischer checked the other envelope. ([And why not? The Soviets had been cheating and their sympathetic allies in Western media are now desperate to deny it.])

Yet Bobby's justifiable distrust, powerful as it is ([because he is a genius, and understands the depths their ruthlessness will stoop to retain the title to bolster the prestige of their sham authoritarianism]) remains subsidiary to his life-long devotion to chess and his passion for perfect and flawless play. Fischer combines chess with the life of a well-to-do Bohemian: he has no home, no permanent address. ([Actually, Robert Fischer does have a “permanent address” of which his personal lawyer acts as caretaker and handling incoming mail: Mr. Bobby Fischer, 280 Madison Ave c/o B. Davis, New York, NY 10016. Further, Dick Cavett asks in 1972, how people can contact Bobby and he states he “I have a mail-drop.” https://youtu.be/zIE3CFNpZ5Y?t=1148])

Unlike the Russians, who emphasize teamwork in training, Bobby works alone with his pocket set. “No grandmaster analyzes as much as Bobby,” says another U.S. grandmaster, Robert Byrne. Gligoric, of Yugoslavia, describes Bobby's dedication like this: “Whenever I am in pleasant company, sipping fine rose win, or when I am playing football or watching a good film, I cannot help remembering Bobby. And I think: at this moment, just like at any other moment, he is sitting by his chessboard, completely indifferent of all pleasures that life offers to him. I have to feel pity and admiration for him. Such a fanaticism cannot be resisted even by such brilliant chessplayers as the Russians—and I believe Spassky won't resist it either.”

([A profound exaggeration about Fischer is uttered here, of course, since in the 1950s, reporters who visited Bobby learned he had interests in baseball, Elvis Presley (music), even reading comic book super-heroes, such as “Batman” comics. During his late adolescent years, Fischer developed an interest in theology and how it might relate to world events, with reporters acknowledging Fischer read U.S. News and World Report magazine, aside of regularly reading his Bible and Plain Truth Magazine from our church, the doomsday cult, Worldwide Church of God, and other Ambassador College correspondence courses and literature to which Fischer was contributing a lion's share of his income. Bobby was not exactly well-rounded, however, to suggest Fischer was forever stuck with his nose glued to a chessboard, and only chess alone, is a profound exaggeration.

Here, Robert Fischer confesses the same during an interview with Dick Cavett in 1972:

CAVETT: “Do you do anything else? Do you like Mystery Stories where you work out the plot?”

FISCHER: “I like to keep up with world news and events that follow…what Ralph [Nader] is doing here.” [Ralph Nader was a guest that night on Dick Cavett's show which speaks volumes about Robert J. Fischer who confesses his interest in reading about Nader's activism in areas of human rights and environmental protections, which would constitute Fischer's further social tendencies and Leftist-leaning interests: “Ralph Nader is an American political activist, author, lecturer, and attorney noted for his involvement in consumer protection, environmentalism, and government reform causes.” See https://nader.org/. Bobby then talks about riding horseback, and how that was a lot of fun. Tennis, swimming, bowling] “…that's a good game.”

CAVETT: “If you were forced to not play for two weeks, would something happen in you?…Any chance it would be good for you to force yourself to not think about chess for two weeks to see if…”

FISCHER: “Well, I haven't really been working at chess for a few days, but I think my sub-conscience mind works on it all the time, so… because it seems when I'm not playing or studying or doing anything and I set down to the board, I got a lot of new ideas. Things are coming to me all the time.”

CAVETT: “And you don't know where they came from?”

FISCHER: “They just come, yeah.”

CAVETT: “Do you dream chess moves?”

FISCHER: “No.” (https://youtu.be/zIE3CFNpZ5Y?t=944 So in other words, Mr. Robert Fischer did not “need” Svetozar Gligoric's “pity”. — To answer Cavett's question, “Where” those effortless strokes of genius came from? Robert Fischer had spent nearly the entirety of his adolescent years absorbed in devoted study of chess books written by some of the foremost authorities, absorbing everything like a sponge into his long-term memory, bits of information that may seem irrelevant, are still retained at the sub-conscience level. Not every bit and piece of information is ever utilized immediately, yet, neither was it forgotten. Tucked away and retained in otherwise dormant layers of long-term memory. In due time, given new information, a need for it's recall, new and improved creative concepts flourish and “come to me,” as Fischer states, without need for conscience effort or work. Those diverse concepts were seeded years before, culminating into new ideas when the opportunity to utilize them is presented. A great artist like Fischer isn't so much “born that way” as much as he develops himself into becoming one.])

DEDICATION and knowledge of book variations, particularly after his own almost invariable favorite opening: 1. P-K4, are part of the explanation of Bobby's strength.

He has been eight times U.S. champion, starting at age 14; his record of 21 successive victories against world class opponents in 1970-71 will probably never be beaten unless he does so himself.

To qualify for his match with Spassky, Bobby defeated Mark Taimanov, of Russia and Bent Larsen of Denmark, 6-0, and ex-champion Tigran Petrosian, of Russia, 6½-2½: this exceptional achievement can be judged by the statistic that at this level of top caliber chess about two thirds of the games are normally drawn.

International rating lists show Fischer not only the best of all time; the computer prediction is that he will beat Spassky 12½-8½, and Ladbrokes quote him as a 2-1 favorite. Commentators speak of “Fischer-fear” among his opponents; his three match victims in the championship eliminators notched up between them two high blood pressures and one nervous exhaustion.

THERE are other chess players who know a mass of opening systems and play with great ambition to win; the extras which set Bobby apart are an ability to isolate a single winning theme from a mass of complications, and a highly-developed capacity for chess visualization and recall. Before Bobby came into world chess, Capablanca was the player with the greatest natural talent:

Capa was simple, direct, logical, always aiming for a favorable endgame here his advantage could be driven home without unnecessary difficulties or risks.

In Bobby's hands, this pure, classical style is almost a cult aiming at a special kind of chess truth. Technically, the Capa element in Fischer's style comes out in his skill in rook and bishop against rook and knight endings, a type of endgame where Spassky's technique is a little suspect. As for visualizing, Bobby is said to remember every major game he has ever played.

Even if the claim may be part of the Fischer publicity machine, there is good scientific evidence to show that natural ability in chess can be diagnosed from a single position.

The Dutch experimental psychologist and chess international Adriaan de Groot in his book, Though and Choice in Chess, tells of a photo of an actual game which was shown as an unfamiliar position to chess players of various strengths for five seconds, after which he asked them to reconstruct it from memory. Differences in chess ranking showed dramatically.

Dr. Max Euwe, former world champion, reconstructed it perfectly, and Fischer or Spassky would be able to do likewise. A lower-ranked master made one small error, but county standard, club and average players made all kinds of mistakes and omissions.

A master can perceive the position in large units such as supporting pieces or pawn structure, and even has an impression within the five seconds of which side has the better game.

WHILE Fischer has talked and trained as if he were already champion Spassky has been preparing with a team of helpers who include Ewfim Geller, the Russian with the best record against Fischer apart from Spassky himself and Nikolai Krogius, a scholarly statistical psychologist whose function seems to be mainly to give homely advice and platitudes.

The third member of Spassky's group, Ivo Nei, is an openings expert who specializes in queen's pawn openings—the minority who forecast Spassky to keep his title reckon that Fischer won't have a good defence if Spassky opens 1. P-Q4.

Boris Spassky, 35, and world champion since he beat Petrosian in 1969, is six years older than Fischer but still within the prime of life period for a chess master which runs from the late twenties to the middle thirties (younger players have not yet developed the experience and stability for consistently good top level results, while older grandmasters get tired in the final phase of the stamina-testing five-hour session which is universal in international contests.)

Spassky, the self-confessed “lazy Russian bear,” has prepared harder for this match than for any other chess event in his life. Whether the preparations will offset his mediocre form of the past two years is an open question.

One fellow chess master has claimed that Boris unconsciously wants to lose the match, and in a recent interview he said that he would feel happier when he was no longer champion.

Though the champion keeps the title if the match is drawn 12-12. Spassky regards this as a handicap for himself: “That rule lures the champion towards cautious tactics with the motto not to lose the game: and such tactics can be terribly dangerous.”

SPASSKY has the burden of defending not only the title itself but the whole Soviet chess hegemony of the past 25 years. The paradox is that Spassky, though a hero of the chess public and Sovietsky Sport's Sportsman of the Year in 1969 has a background of conflict with chess officials and was reportedly openly critical of the invasion of Czechoslovakia.

How will the match go and who will win? On results and ratings there is only one player in it — Fischer. There are just three factors which give Spassky a chance of keeping his title. First is his excellent personal record against Fischer of 4-1, which has been achieved by clever psychological chess, steering the game by pawn sacrifices into just the unclear situations, without positional landmarks which Fischer dislikes. “Yeah, Spassky used to defeat me, but those were awfully bad games,” said Bobby to an interviewer.

SECONDLY there is the technical factor that the defenses which Fischer relies upon against the queen's pawn—the Grunfeld, King's Indian and Benoni — all have some theoretical doubts attached to them at the moment. If Spassky can blunt Fischer's attacks when the American is White and can himself score well with 1. P-Q4, then he's in business.

Finally, Fischer's supporters will fear most of all that Bobby's self-destructive streak which has produced walkouts from major world events ([a couple walkouts, when organizers and a referee were breaking the rules, unseemly behavior such as discrimination against the religious observance of the seventh day Sabbath, then unleashing a flood of antisemitic smears to excuse such behavior. And in the other case, the referee never acquired Fischer's consent, changing the scheduled start time to accommodate the referee's personal scheduled trip to the San Francisco Open. The whole tournament between Fischer and Reshevsky ended in a trainwreck, due to thoughtless actions and bad faith on behalf of judges and organizers]) will produce the first default in a world championship. Bobby has criticized the choice of Iceland for the match as “primitive” and has complained that he will be spied on by the Soviet Russians and badgered by the press while he stays there. ([which, is no overstatement of the current events. Not only spied on, but outlandish exaggerations and allegations… contradictory and offensively refutable allegations flooding the world press to sell papers with a sensational headline and mockery of actual events])

If Bobby finds himself two or three games down, there is a risk that the match will end prematurely ([and that's precisely what the Soviets were counting on when they misled Fischer to erroneously assume the “cameras” would consist of automated, stationary video tape “closed-circuit cameras” versus crews of visually and audibly disruptive men, responsible for operating several large, bulky television cameras… swarming Fischer in the main auditorium, hoping Fischer's concentration might be blown resulting in the forfeit or loss of some games and gambling on Fischer to just throw in the towel and default the challenge for the title. But the Soviets miscalculated]). On balance however, I expect Fischer to win comfortably though not overwhelmingly, with a final margin between 12½-9½ and 12½-6½.

Chess No Longer Considered A Game for Slow-Moving Graybeards 19 Jul 1972, Wed The Ottawa Journal (Ottawa, Ontario, Canada) Newspapers.com

Chess No Longer Considered A Game for Slow-Moving Graybeards 19 Jul 1972, Wed The Ottawa Journal (Ottawa, Ontario, Canada) Newspapers.com

The Sheboygan Press Sheboygan, Wisconsin Wednesday, July 19, 1972 - Page 7

Spassky Nearly Defeated Fischer In Fourth Game by Isaac Kashdan

Following is an analysis of the fourth Fischer-Spassky chess game, written for The Associated Press by Isaac Kashdan, an international chess grandmaster.

Los Angeles (AP)—Boris Spassky came close to defeating Bobby Fischer in the fourth game of their world championship chess match.

Spassky was the aggressor for the first time, building up a powerful attack, but he missed his way by reversing moves at the critical point. On his 29th turn, Spassky should have played B-Q3, threatening mate. Fischer would be forced to move his king. Then on 30 R-R1 would follow.

This order of moves would avoid the exchange of queens that Fischer was able to effect in the game.

With the black rook coming into play, via R3 or R5, and the white king exposed, the attack would have proved irresistible.

After the exchange of queens, on the other hand, Fischer's king was quite safe. With the forces reduced on both sides, a draw was a proper result.

Spassky's first move was a surprise to the experts. He adopted the Sicilian Defense, which he rarely plays, but which is standard in Fischer's repertoire.

Fischer used the Sozin variation, a favorite of his marked by the development of his king bishop on the queen side.

Spassky evidently was well prepared. On his 13th move he offered a pawn which would open useful lines for his pieces if Fischer accepted. Fischer rarely refuses such challenges, and he took the pawn.

Wiser probably would have been 14. QR-K1, with a firm grip on the center pawns. With his 17th move, Fischer allowed Spassky to dominate two major diagonals with his bishop. Spassky's queen also had an effective post. At move 17, Q-K3 was probably superior for Fischer although he would have encountered difficulties in any case.

Spassky needed additional force to keep his attack going, and he found it in his king rook pawn, which he advanced on his 21st and 23rd moves.

Fischer found defensive measures and was able to hold the line and even maintain the pawn plus.

Spassky also found the best moves until the slip on the 29th. Curiously, it was on the 29th move that Fischer blundered in the first match game.

Spassky has never beaten Fischer with the black pieces. He has won four times and lost once with white. With black he has drawn three times, including the present game.

The Central New Jersey Home News New Brunswick, New Jersey Wednesday, July 19, 1972 - Page 16

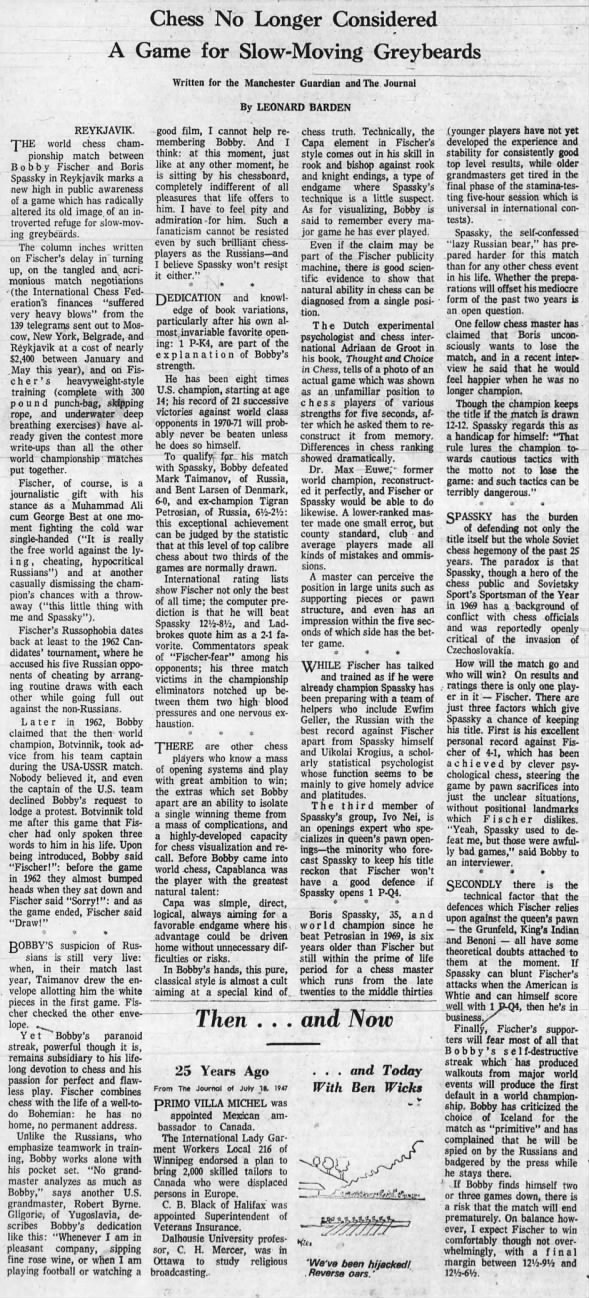

A Word From the Sidelines

Fred Kramer, left, a representative of U.S. challenger Bobby Fischer, has a word with Fischer upon their arrival at Laugardalsholl Hall, in Reykjavik, Iceland, for the fourth game in the championship chess match with Boris Spassky. Fischer, who had first move, arrived 10 minutes after the clock was started, signaling the beginning of play. AP Photo.

A Word From the Sidelines 19 Jul 1972, Wed The Central New Jersey Home News (New Brunswick, New Jersey) Newspapers.com

A Word From the Sidelines 19 Jul 1972, Wed The Central New Jersey Home News (New Brunswick, New Jersey) Newspapers.com

Dayton Daily News Dayton, Ohio Wednesday, July 19, 1972 - Page 3

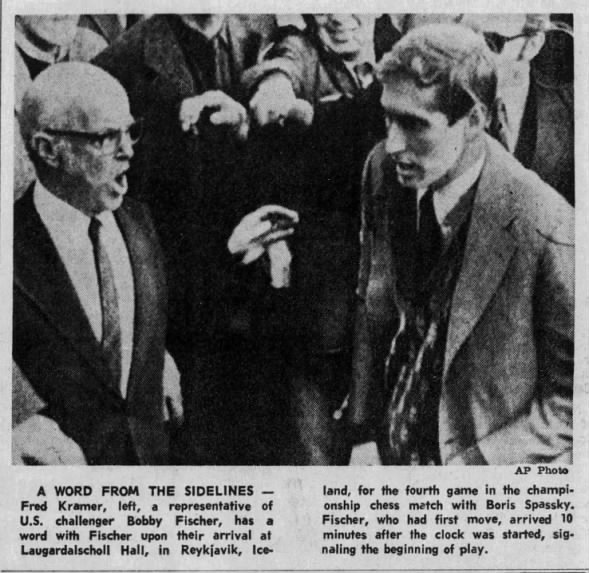

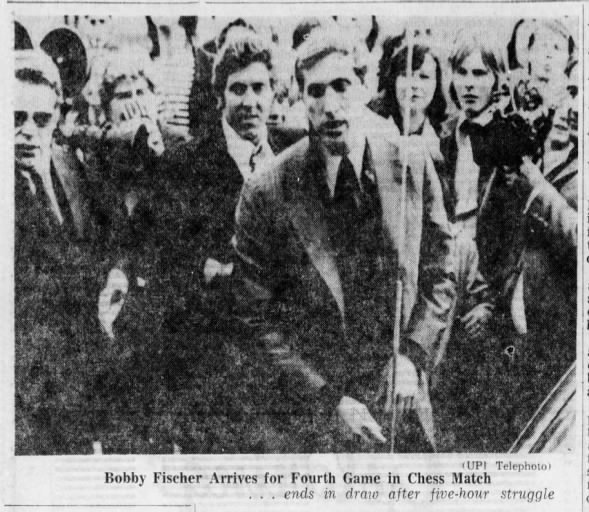

Here's How Board Looked When Spassky Offered Draw

Fischer accepted gesture with almost imperceptible nod.

Here's How Board Looked When Spassky Offered Draw 19 Jul 1972, Wed Dayton Daily News (Dayton, Ohio) Newspapers.com

Here's How Board Looked When Spassky Offered Draw 19 Jul 1972, Wed Dayton Daily News (Dayton, Ohio) Newspapers.com

Dayton Daily News Dayton, Ohio Wednesday, July 19, 1972 - Page 3

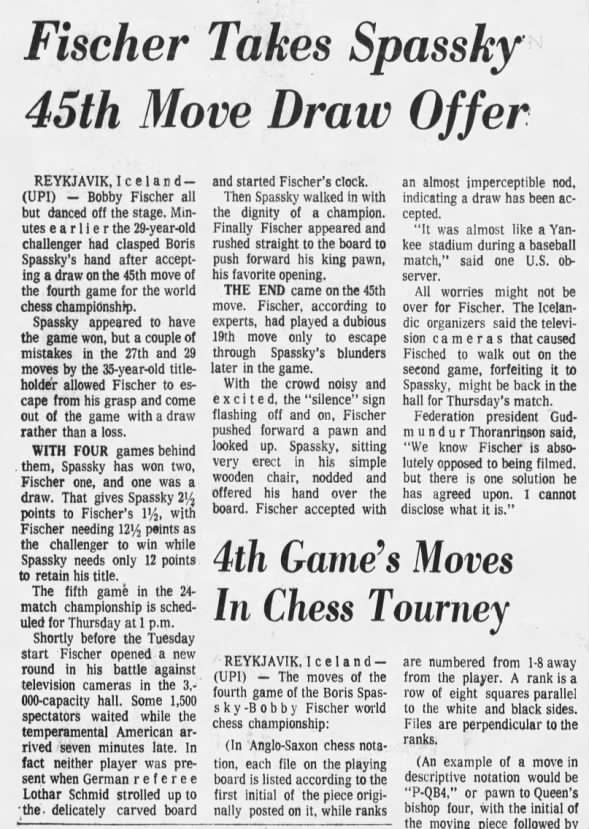

Fischer Takes Spassky 45th Move Draw Offer

Reykjavik, Iceland—(UPI)—Bobby Fischer all but danced off the stage. Minutes earlier the 29-year-old challenger had clasped Boris Spassky's hand after accepting a draw on the 45th move of the fourth game for the world chess championship.

Spassky appeared to have the game won, but a couple of mistakes in the 27th and 29th moves by the 35-year-old titleholder allowed Fischer to escape from his grasp and come out of the game with a draw rather than a loss.

WITH FOUR games behind them, Spassky has won two, Fischer one, and one was a draw. That gives Spassky 2½ points Fischer's 1½, with Fischer needing 12½ points as the challenger to win while Spassky needs only 12 points to retain his title.

The fifth game in the 24-match championship is scheduled for Thursday at 1 p.m.

Shortly before the Tuesday start Fischer opened a new round in his battle against ([crews of disruptive men operating]) television cameras in the 3,000-capacity hall. Some 1,500 spectators waited while the American challenger arrived seven minutes late. In fact neither player was present when German referee Lothar Schmid strolled up to the delicately carved board and started Fischer's clock.

Then Spassky walked in with the dignity of a champion. FInally Fischer appeared and rushed straight to the board to push forward his king pawn, his favorite opening.

THE END came on the 45th move. Fischer, according to experts, had played a dubious 19th move only to escape through Spassky's blunders later in the game.

With the crowd noisy and excited, the “silence” sign flashing off and on, Fischer pushed forward a pawn and looked up. Spassky, sitting very erect in his simple wooden chair, nodded and offered his hand over the board. Fischer accepted with an almost imperceptible nod, indicating a draw has been accepted.

“It was almost like a Yankee stadium during a baseball match,” said one U.S. observer.

All worries might not be over for Fischer. The Icelandic organizers said the television cameras that caused Fischer to walk out on the second game, forfeiting it to Spassky, might be back in the hall for Thursday's match.

Federation president Gudmundur Thorarinsson said “We know Fischer is absolutely opposed to being filmed ([by disruptive crews of camera men, hired to disruptively operate the television cameras]), but there is one solution he has agreed upon. I cannot disclose what it is.” ([Perhaps for instance, the “solution” Fischer was misled to believe by Icelandic/Soviet organizers and Chester Fox, Inc would actually be the case from the start: “…some kind of video tape film that didn't make any noise, just, nobody around to operate them, just sort of stationary…” as quoted by Robert Fischer in November 1972 to Johnny Carson on national U.S. television.])

Fischer Takes Spassky 45th Draw Offer 19 Jul 1972, Wed Dayton Daily News (Dayton, Ohio) Newspapers.com

Fischer Takes Spassky 45th Draw Offer 19 Jul 1972, Wed Dayton Daily News (Dayton, Ohio) Newspapers.com

The Sydney Morning Herald Sydney, New South Wales, Australia Wednesday, July 19, 1972 - Page 4

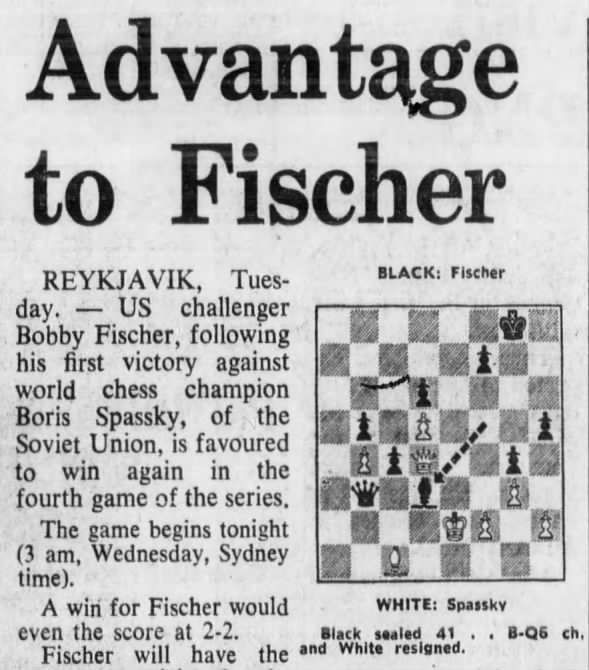

Advantage to Fischer

Reykjavik, Tuesday. — U.S. challenger Bobby Fischer, following his first victory against world chess champion Boris Spassky, of the Soviet Union, is favoured to win again in the fourth game of the series.

The game begins tonight (3 a.m. Wednesday, Sydney time).

A win for Fischer would even the score at 2-2.

Fischer will have the advantage tonight of making the opening move with the White pieces for the first time in the match.

In winning the third game, Fischer gave chess-loving Icelanders a sample of his attacking brilliance and his eye for original moves.

The game was adjourned on Sunday with Spassky in such a hopeless position that he resigned on the resumption last night, immediately after seeing Fischer's sealed 41st move. It was B-Q6ch.

There is still a shadow over the match: the as-yet-unsettled issue of ([disruptive men operating]) television coverage.

Fischer has protested against moving play back to the giant auditorium from the private room in the hall where the third game started. Spassky has requested that play continue on stage.

Father William Lombardy, Fischer's second, told newsmen after the third game: “This could be the turning point.”

“Don't forget Bobby came through a lot of trouble.

“After four defeats and two draws against Spassky (including previous non-championship games) he has finally broken the ice with more to come. I think it was one of Bobby's best and most important wins.”

Advantage to Fischer 19 Jul 1972, Wed The Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney, New South Wales, Australia) Newspapers.com

Advantage to Fischer 19 Jul 1972, Wed The Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney, New South Wales, Australia) Newspapers.com

The Times Shreveport, Louisiana Wednesday, July 19, 1972 - Page 1

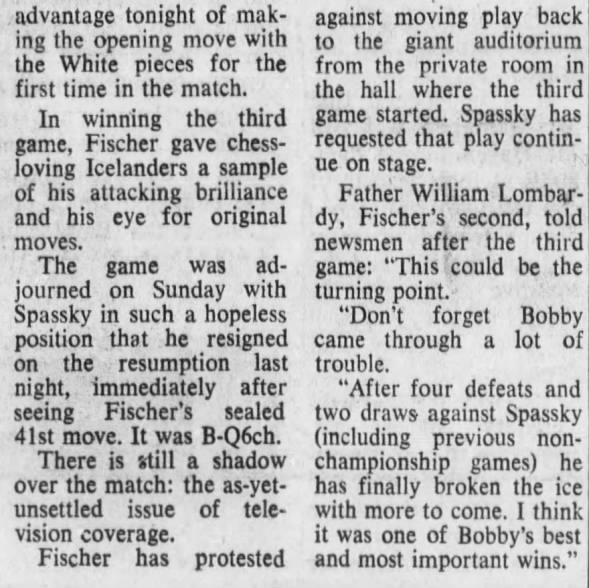

Bobby Fischer Arrives for Fourth Game in Chess Match

…ends in draw after five-hour struggle.

Bobby Fischer Arrives for Fourth Game in Chess Match 19 Jul 1972, Wed The Times (Shreveport, Louisiana) Newspapers.com

Bobby Fischer Arrives for Fourth Game in Chess Match 19 Jul 1972, Wed The Times (Shreveport, Louisiana) Newspapers.com

Newsday (Suffolk Edition) Melville, New York Wednesday, July 19, 1972 - Page 79

Spassky Arrives for 4th Game — AP Photo

Spassky Arrives for 4th Game 19 Jul 1972, Wed Newsday (Suffolk Edition) (Melville, New York) Newspapers.com

Spassky Arrives for 4th Game 19 Jul 1972, Wed Newsday (Suffolk Edition) (Melville, New York) Newspapers.com

The Boston Globe Boston, Massachusetts Wednesday, July 19, 1972 - Page 56

Fischer-Spassky World Chess

At Reykjavik, Iceland

Fourth Match

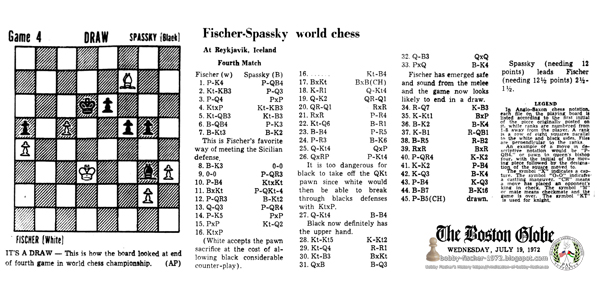

Fischer (White) Spassky (Black)

1. e4 c5

2. Nf3 d6

3. d4 cxd4

4. Nxd4 Nf6

5. Nc3 Nc6

6. Bc4 e6

7. Bb3 Be7

This is Fischer's favorite way of meeting the Sicilian defense.

8. Be3 O-O

9. O-O a6

10. f4 Nxd4

11. Bxd4 b5

12. a3 Bb7

13. Qd3 a5

14. e5 dxe5

15. fxe5 Nd7

16. Nxb5

(White accepts the pawn sacrifice at the cost of allowing black considerable counter-play).

16. … Nc5

17. Bxc5 Bxc5+

18. Kh1 Qg5

19. Qe2 Rad8

20. Rad1 Rxd1

21. Rxd1 h5

22. Nd6 Ba8

23. Bc4 h4

24. h3 Be3

25. Qg4 Qxe5

26. Qxh4 g5

It is too dangerous for black to take off the QN pawn since white would then be able to break through black's defenses with NxP.

27. Qg4 Bc5

Black now definitely has the upper hand.

28. Nb5 Kg7

29. Nd4 Rh8

30. Nf3 Bxf3

31. Qxf3 Bd6

32. Qc3 Qxc3

33. bxc3 Be5

Fischer has emerged safe and sound from the melee and the game now looks likely to end in a draw.

34. Rd7 Kf6

35. Kg1 Bxc3

36. Be2 Be5

37. Kf1 Rc8

38. Bh5 Rc7

39. Rxc7 Bxc7

40. a4 Ke7

41. Ke2 f5

42. Kd3 Be5

43. c4 Kd6

44. Bf7 Bg3

45. c5+ 1/2-1/2

Spassky (needing 12 points) leads Fischer (needing 12½ points) 2½-1½.

CAPTION: It's A Draw—This is how the board looked at end of fourth game in world chess championship. (AP)

In Anglo-Saxon chess notation, each file on the playing board is listed according to the first initial of the piece originally posted on it, while ranks are numbered from 1-8 away from the player. A rank is a row of eight squares parallel to the white and black sides. Files are perpendicular to the ranks.

An example of a move in descriptive notation would be “P-QB4” or pawn to queen's bishop four, with the initial of the moving piece followed by the designation of the square moved to.

The symbol “X” indicates a capture. The symbol &lduqo;O-O” indicates a castling maneuver. “CH” means a move has placed an opponent's king in check. The symbol “M” or mate means checkmate and the game is over. The symbol “KT” is used for knight.

The Los Angeles Times Los Angeles, California Wednesday, July 19, 1972 - Page 1

Spassky's 29th Move Provides Turning Point by Isaac Kashdan

Boris Spassky outplayed Bobby Fischer in the fourth game of their chess match, built up a winning position, and then missed his opportunity by reversing moves at a critical moment.

The diagram below shows the position after Fischer's 29th move. Spassky's queen and two bishops are on long diagonals down on the white king.

Fischer is a pawn ahead, but he would gladly settle for a draw in view of the dangers he can foresee. Spassky played 29. R-R1, after which Fischer could simplify the game. Three moves later he exchanged queens and the danger was over.

The correct plan for Spassky was 29. B-Q3, threatening mate on the next move. Fischer would have no choice but to move his king. Then comes 30. R-R1, the move Spassky made too early.

If Fischer then continued with the same defensive plan, the continuation would be: 31. N-B3 BxN; 32. QxB Q-R7ch; 33. K-B1 R-R3.

The queens would remain on the board, and with the white king exposed, Fischer's game would soon collapse.

Spassky's surprised the experts by adopting the Sicilian Defense, which he rarely plays. It is Fischer's favorite opening, and he is probably more familiar with its ramifications than anyone else.

Spassky had evidently prepared for the variations that Fischer generally uses. On his 13th move he offered a pawn which would open useful lines for his pieces if Fischer accepted.

Fischer rarely refuses such challenges, and he took the pawn. Probably wiser would have been the developing move 14. QR-K1, to maintain his center pawn formation.

With his 17th move Fischer allowed Spassky to dominate two major diagonals with his bishops. Spassky's queen also had an effective post. Fischer might have improved his chances with 17. Q-K3, although he would still have encountered difficulties.

Spassky needed additional force to keep his attack going, and he found it in his king rook pawn, which he advanced on his 21st and 23rd moves. Fischer defended carefully, and was able to hold for a time, even retaining his pawn plus.

Spassky also found the best moves until the slip on his 29th turn. Curiously it was also on the 29th move that Fischer blundered in the first match game.

Spassky has never beaten Fischer with the black pieces. He has won four and lost one when playing white. With black he has drawn three times, including the present game.

The Age Melbourne, Victoria, Australia Wednesday, July 19, 1972 - Page 9

“Actually, I'm not too keen on my terms either — 10 years in Siberia if I lose.”

Actually, I'm Not Too Keen on My Terms Either 19 Jul 1972, Wed The Age (Melbourne, Victoria, Australia) Newspapers.com

Actually, I'm Not Too Keen on My Terms Either 19 Jul 1972, Wed The Age (Melbourne, Victoria, Australia) Newspapers.com

The Age Melbourne, Victoria, Australia Wednesday, July 19, 1972 - Page 10

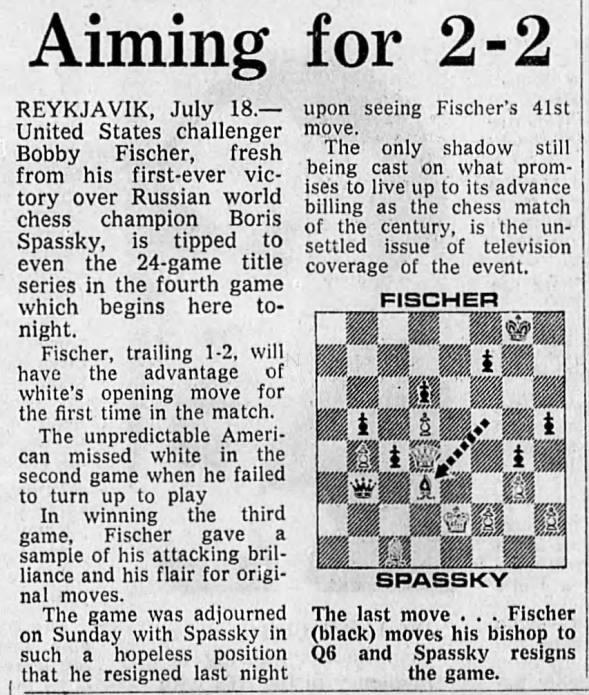

Aiming for 2-2

Reykjavik, July 18—United States challenger Bobby Fischer, fresh from his first-ever victory over Russian world chess champion Boris Spassky, is tipped to even the 24-game title series in the fourth game which begins here tonight.

Fischer, trailing 1-2, will have the advantage of white's opening move for the first time in the match.

([The American challenger missed his chance to play white in the second game due to the disruptive crews of camera men which Fischer was well within his rights, as prescribed in the rules, to protest and demand removal of cameras and the audibly and visibly disruptive men, hired to operate them and blow Fischer's concentration.])

In winning the third game, Fischer gave a sample of his attacking brilliance and his flair for original moves.

The game was adjourned on Sunday with Spassky in such a hopeless position that he resigned last night upon seeing Fischer's 41st move.

The only shadow still being cast on what promises to live up to its advance billing as the chess match of the century, is the unsettled issue of television coverage of the event.

Aiming For 2-2 19 Jul 1972, Wed The Age (Melbourne, Victoria, Australia) Newspapers.com

Aiming For 2-2 19 Jul 1972, Wed The Age (Melbourne, Victoria, Australia) Newspapers.com

The San Francisco Examiner San Francisco, California Wednesday, July 19, 1972 - Page 35

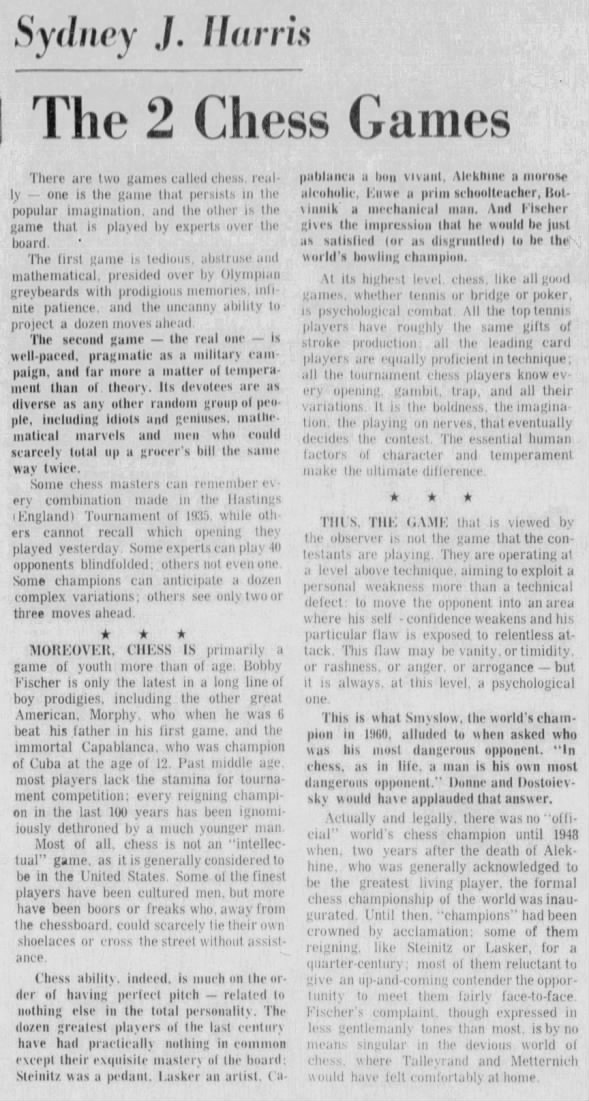

The 2 Chess Games by Sydney J. Harris

There are two games called chess really — one is the game that persists in the popular imagination, and the other is the game that is played by experts over the board.

The first game is tedious, abstruse and mathematical, presided over by Olympian graybeards with prodigious memories, infinite patience, and the uncanny ability to project a dozen moves ahead.

The second game — the real one — is well-paced, pragmatic as a military campaign, and far more a matter of temperament than of theory. Its devotees are as diverse as any other random group of people, including mathematical marvels and men who could scarcely total up a grocer's bill the same way twice.

Some chess masters can remember every combination made in the Hastings (England) Tournament of 1935, while others cannot recall which opening they played yesterday. Some experts can play 40 opponents blindfolded, others not even one. Some champions can anticipate a dozen complex variations; others see only two or three moves ahead.

MOREOVER, CHESS IS primarily a game of youth more than of age. Bobby Fischer is only the latest in a long line of boy prodigies, including the other great American, Morphy, who when he was 6 beat his father in his first game, and the immortal Capablanca, who was champion of Cuba at the age of 12. Past middle age, most players lack the stamina for tournament competition; every reigning champion in the last 100 years has been ignominiously dethroned by a much younger man.

Most of all, chess is not an “intellectual” game, as it is generally considered to be in the United States. Some of the finest players have been cultured men, but more, away from the chessboard, could scarcely tie their own shoelaces or cross the street without assistance.

Chess ability, indeed, is much on the order of having perfect pitch — related to nothing else in the total personality. The dozen greatest players of the last century have had practically nothing in common except their exquisite mastery of the board; Steinitz was a pedant, Lasker an artist, Capablanca a bon vivant, Alekhine a morose alcoholic, Euwe a prim schoolteacher, Botvinnik a mechanical man. And Fischer gives the impression that he would be just as satisfied to be the world's bowling champion.

At its highest level, chess like all good games, whether tennis or bridge or poker, is psychological combat. All the top tennis players have roughly the same gifts of stroke production; all the leading card players are equally proficient in technique; all the tournament chess players know every opening gambit, trap, and all their variations. It is the boldness, the imagination, the playing on nerves, that eventually decides the contest. The essential human factors of character and temperament make the ultimate difference.

THUS, THE GAME that is viewed by the observer is not the game that the contestants are playing. They are operating at a level above technique, aiming to exploit a personal weakness more than a technical defect to move the opponent into an area where his self-confidence weakens and his particular flaw is exposed to relentless attack. This flaw may be vanity, or timidity, or rashness, or anger, or arrogance -- but it is always, at this level,a psychological one.

This is what Smyslov, the world champion 1960, alluded to when asked who was his most dangerous opponent. “In chess, as in life, a man is his own most dangerous opponent.” Donne and Dostoievsky would have applauded that answer.

([Not emphasized by the author, however, from the time Robert Fischer reached 13 years of age till the battle over the world crown in 1972, the “other chess game” known as “Soviet Machiavellianism” was in full swing, to thwart Fischer's ambitions, every opportunity.])

Actually and legally, there was no “official” world's chess champion until 1948 when, two years after the death of Alekhine, who was generally acknowledged to be the greatest living player, the formal chess championship of the world was inaugurated. Until then, “champions” had been crowned by acclamation; some of them reigning, like Steinitz or Lasker, for a quarter-century; most of them reluctant to give an up-and-coming contender the opportunity to meet them fairly face-to-face. Fischer's complaint, is by no means singular in the devious world of chess, where Talleyrand and Metternich would have felt comfortably at home.

The 2 Chess Games 19 Jul 1972, Wed The San Francisco Examiner (San Francisco, California) Newspapers.com

The 2 Chess Games 19 Jul 1972, Wed The San Francisco Examiner (San Francisco, California) Newspapers.com

The Orlando Sentinel Orlando, Florida Wednesday, July 19, 1972 - Page 6

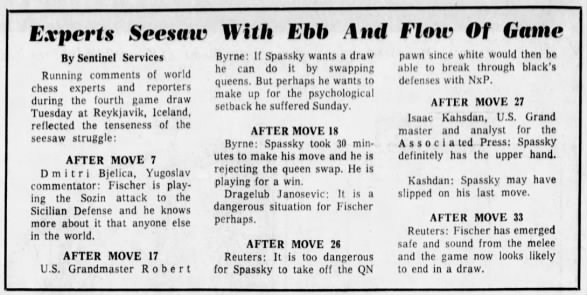

Experts Seesaw With Ebb and Flow of Game by Sentinel Services

Running comments of world chess experts and reporters during the fourth game draw Tuesday at Reykjavik, Iceland, reflected the tenseness of the seesaw struggle:

After Move 7

Dmitri Bjelica, Yugoslav commentator: Fischer is playing the Sozin attack to the Sicilian Defense and he knows more about it than anyone else in the world.

After Move 17

U.S. Grandmaster Robert Byrne: If Spassky wants a draw he can do it by swapping queens. But perhaps he wants to make up for the psychological setback he suffered Sunday.

After Move 18:

Byrne: Spassky took 30 minutes to make his move and he is rejecting the queen swap. He is playing for a win.

Dragelub Janosevic: It is a dangerous situation for Fischer perhaps.

After Move 26

Reuters: It is too dangerous for Spassky to take off the QN pawn since white would then be able to break through black's defenses with NxP.

After Move 27:

Isaac Kashdan, U.S. Grand master and analyst for the Associated Press: Spassky definitely has the upper hand.

Kashdan: Spassky may have slipped on his last move.

After Move 33

Reuters: Fischer has emerged safe and sound from the melee and the game now looks likely to end in a draw.

Experts Seesaw With Ebb and Flow of Game 19 Jul 1972, Wed The Orlando Sentinel (Orlando, Florida) Newspapers.com

Experts Seesaw With Ebb and Flow of Game 19 Jul 1972, Wed The Orlando Sentinel (Orlando, Florida) Newspapers.com

The Des Moines Register Des Moines, Iowa Wednesday, July 19, 1972 - Page 4

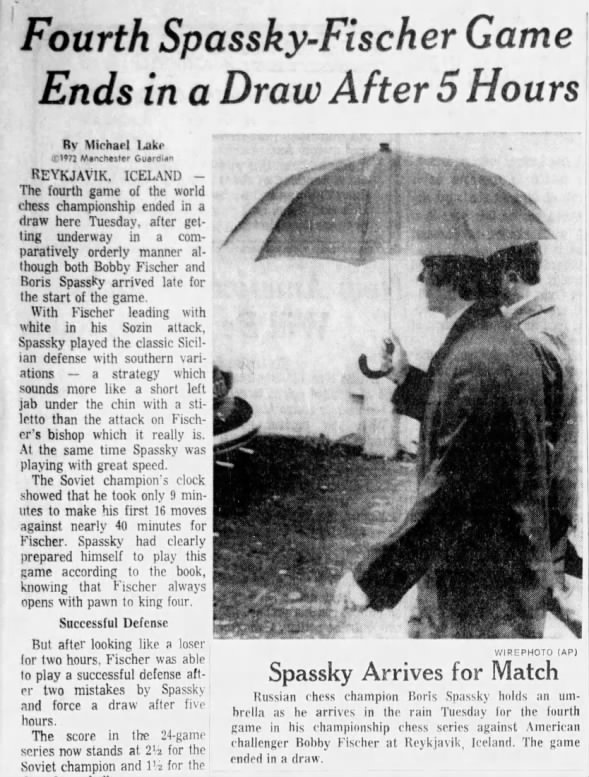

Fourth Spassky-Fischer Game Ends in a Draw After 5 Hours by Michael Lake, 1972 Manchester Guardian

Reykjavik, Iceland—The fourth game of the world chess championship ended in a draw here Tuesday, after getting underway in a comparatively orderly manner although both Bobby Fischer and Boris Spassky arrived late for the start of the game.

With Fischer leading with white in his Sozin attack, Spassky played the classic Sicilian defense with southern variations — a strategy which sounds more like a short left jab under the chin with a stiletto than the attack on Fischer's bishop which it really is. At the same time Spassky was playing with great speed.

The Soviet champion's clock showed that he took only 9 minutes to make his first 16 moves against nearly 40 minutes for Fischer. Spassky had clearly prepared himself to play this game according to the book, knowing that Fischer always opens with pawn to king four.

Successful Defense

But after looking like a loser for two hours, Fischer was able to play a successful defense after two mistakes by Spassky and force a draw after five hours.

The score in the 24-game series now stands at 2½ for the Soviet champion and 1½ for the American challenger.

They called it quits at the forty-fifth move. The fight had been hard with a string of startling turnabouts.

Each contestant got a half-point for the draw. Spassky, 35, won the first game and got the second by forfeit when Fischer ([boycotted the unethical refusal of organizers to obey the rules and upon Fischer's demand, remove crews of camera men hired to create auditory and visual disruptions, which interfered with Fischer's concentration during Game #1, leading up to his setting out Game #2 in protest]). The 29-year-old American won the third.

Yugoslav grandmaster Svetozar Gligoric said Spassky had made a bad error on the twenty-ninth move, throwing away the chance of a victory.

U.S. grandmaster Robert Byrne said Spassky, playing at a slight disadvantage with the black pieces, could have pocketed a draw at the eighteenth move by forcing an exchange of queens.

But the Russian chose to go for a victory. The game was packed with surprises, first white and then black setting the pace.

Spectators bet first on Fischer, then on Spassky and then on Fischer again.

For the first time in the series, Spassky was late in arriving — but not so late as Fischer. The Soviet champion walked onstage four minutes after the clock started. The American chess whiz from Brooklyn was 10 minutes overdue in the 2,500-seat auditorium.

Spassky made his first eight moves in less than two minutes, having obviously prepared his defense well in advance.

Fischer, behind 2-1 in the 24-game match, was also prepared, for he played his first seven moves in less than three minutes.

For his eighth move, however, Fischer took 10 minutes, the intellectual battle was on in earnest.

There were no move or TV cameras in the auditorium, said Gudmundur Thorarinsson, president of the Icelandic Chess Federation.

Fourth Spassky-Fischer Game Ends in a Draw After 5 Hours 19 Jul 1972, Wed The Des Moines Register (Des Moines, Iowa) Newspapers.com

Fourth Spassky-Fischer Game Ends in a Draw After 5 Hours 19 Jul 1972, Wed The Des Moines Register (Des Moines, Iowa) Newspapers.com

The Guardian London, Greater London, England Wednesday, July 19, 1972 - Page 26

Spassky and Fischer Draw on the 45th by Leonard Barden

The fourth game of the world chess championship match in Reykjavik between Boris Spassky and Bobby Fischer finished in a draw last night on the 45th move. The game reached a completely level ending with bishops of opposite colors and four pawns on each side. Spassky now leads the 24-game series by 2½ points to 1½, with the next game scheduled for tomorrow night.

It was an epic fighting encounter which did equal credit to Spassky's seconds for their skillful preparation of a new theoretical idea, to Spassky himself for the vigour with which he sacrificed a pawn and organized his pieces for a combined attack against the American king, and to Fischer for the brilliant defensive skill with which he regrouped his scattered forces and exchanged off the most dangerous attacking pieces.

Fischer survived in this game pressures which would have broken the morale of many lesser chess masters. The clocks after 16 moves already told the tale of a thoroughly researched Russian secret weapon.

Spassky generalled his queen, rook, and bishop pair for a massive assault, and by move 28 it looked as if Fischer's knight and bishop, which had been driven to the queen's flank by Spassky's prepared pawn sacrifice, were useless as defenders.

The key to Fischer's play was the plan which brought back his knight into defense and enabled him to break Spassky's hopes of checkmate by exchanging off the queens.

Earlier, Spassky's well planned chess enabled him to offer Fischer a pawn on move 13.

Chicago Tribune Chicago, Illinois Wednesday, July 19, 1972 - Page 80

Chicago Chess Addicts Find Lakefront Home by Frank Blatchford

“You fool, I told you not to make that mistake again,” shouted Nate, the stockbroker, at Andre, the busboy, his mock anger reverberating thru the lakefront chess pavilion just south of the North Avenue Beach.

Every afternoon when the weather's nice, Nathan Rochmes, who's in his fifties, grabs his plastic satchel and rushes out of his office as soon as the day's trading is over. At the chess pavilion he takes out the battered set of chessmen, a cushion for himself, and begins to play.

Usually he'll find the same players there, Andre Nairveau, a 20-year-old busboy, John, Kathy, and nearly two dozen others.

One can't spend an hour watching the players without realizing that chess is more than a world championship match between Boris Spassky of Russia and Bobby Fischer of the United States.

Chess is an addiction, a state of mind, a force that binds men.

It spans the generation gap. It fills a hungry stomach at lunch time. It whiles away lonely hours for the old and fascinates the young.

On a recent afternoon 11 games proceeded at once in the pavilion, which commands a magnificent view of the downtown skyline.

“Most of these guys out here are crazy over chess,” John said. “I'm one of 'em. We come out here just about every day from May thru Labor Day. With the lake and the breeze this has to be one of the most beautiful spots in the city.

“This morning we worked out the third Spassky-Fischer game and figured Spassky couldn't last four moves.

“But now everybody's forgotten about that. They're all engaged in their own games. The concentration is so deep it's almost like a mystical spell. A girl could walk right thru here in a bikini and nobody would notice.”

Chicago Chess Addicts Find Lakefront Home 19 Jul 1972, Wed Chicago Tribune (Chicago, Illinois) Newspapers.com

Chicago Chess Addicts Find Lakefront Home 19 Jul 1972, Wed Chicago Tribune (Chicago, Illinois) Newspapers.com

Daily News New York, New York Wednesday, July 19, 1972 - Page 4

(Soviets Wanted Media Blackout. Used Disruptive Camera Men to Achieve It.) Battle Ends in Draw by Robert Byrne

Reykjavik, Iceland, July 18—Bobby Fischer of Brooklyn and Boris Spassky of Russia ended the fourth game of the world chess championship today in a draw after 45 moves and five hours.

Fischer used the opening he almost always employs when he has the first move of the game, advancing his king's pawn two squares. Spassky, in a surprise start, used the Sicilian defense, which is Fischer's favorite.

Previously, Boris considered the two-edged game arising from this unbalanced formation to be too wild for serious contests. But he went all-out tonight, sacrificing a pawn at the 16th move to deflect Fischer's knight to the queen's side, thus buying time to mount a menacing attack on the other wing.

Holds 1-Point Lead

The draw left Spassky still with a 1-point advantage, over Fischer, 2½ to 1½, in the $250,000 match. The fifth game is set for Thursday at 5 p.m. (1 p.m. New York time). A player wins if he gets 12½ points. If the match goes 24 games and is even, Spassky retains the crown.

After the seventh move, huge “silence” signs in the halls began flashing on and off to quiet a murmur of excitement inspired by Spassky's move of a bishop to king 2. The Russians left the stage after making it.

Fischer then studied the board for seven full minutes before moving his queen's bishop to king 3. Spassky swept back on stage immediately to make his next move.

Caught unprepared for Boris' novel counter-attacking strategy, Bobby consumed an enormous amount of time in the early middle game trying hard to transport his minor pieces to the king's win to fight off the terrific power of Spassky's bishop's bearing down on adjacent diagonals, augmented by the queen.

The only way he could meet the vicious thrust of Spassky's king's rook pawn, which threatened to rip up the last defense, was to block it by his 24th move, P-R3.

But that move inevitably weakened the black squares around his king and demanded hair's breath tactics to survive. By rushing his knight back to KB3 at the 30th move, and forcing the exchange of queens next, he squeaked through to safety in a drawn bishops of opposite color ending.

It is possible that Boris missed a good chance at his 27th move, which gave Bobby a breather. Instead … R-Q1; 28. N-N5 RxRch; 29. QxR Q-N6, threatening mate at N7 and R6 would have been impossible to parry, for if 30. Q-Q8ch, K-N2; 31. QxB then … Q-K8ch, 32. K-R2 B-N8ch; 33. K-R1 B-B7ch; 34. K-R2 Q-N8 mate. Fischer would have had to try 28. NxP RxRch; 29. QxR, but it isn't clear how he could get a perpetual check after the reply 29. … Q-N6.

Soviets Wanted Media Blackout. Used Disruptive Camera Men to Achieve It. Battle Ends in Draw 19 Jul 1972, Wed Daily News (New York, New York) Newspapers.com

Soviets Wanted Media Blackout. Used Disruptive Camera Men to Achieve It. Battle Ends in Draw 19 Jul 1972, Wed Daily News (New York, New York) Newspapers.com

The Windsor Star Windsor, Ontario, Canada Wednesday, July 19, 1972 - Page 11

Fischer Fan

Sir: It is a great reflection on the intelligence of Windsor people when The Star editorial can sneer at Bobby Fischer who, it is still possible, could become the only world chess champ the English-speaking world has produced.

Win or lose he is internationally a man of respect and stature but not, it seems in oh so smug Windsor. Shame.

([Most certainly so, due to Soviets influence in western media undermining the free press, suppressing accurate news accounts whilst unquestioning recycling of patent Soviet propaganda.])

Fischer Fan 19 Jul 1972, Wed The Windsor Star (Windsor, Ontario, Canada) Newspapers.com

Fischer Fan 19 Jul 1972, Wed The Windsor Star (Windsor, Ontario, Canada) Newspapers.com

Rocky Mount Telegram Rocky Mount, North Carolina Wednesday, July 19, 1972 - Page 13

Personally Speaking... by Ronnie Smith

That ancient, ancient game of chess is once more capturing the excitement of millions of fans across the world.

With the world championship being played in Reykjavik, Iceland between champion Boris Spassky and challenger Bobby Fischer, small chessboards have sprung up in nearly every conceivable corner of the world.

For the past week, wire services have been sending pictures constantly from all parts of the world showing various people in the act of playing the mind-bending game. One picture showed a young boy, approximately five years old, playing ten games at the same time against opponents older than himself. Another picture was a beach scene in which a giant chessboard had been spread out on the sand, and the participants were playing the game while soaking up some sun.

The game of chess has endured many centuries, but never seems to be checkmated in popularity.

Personally Speaking by Ronnie Smith 19 Jul 1972, Wed Rocky Mount Telegram (Rocky Mount, North Carolina) Newspapers.com

Personally Speaking by Ronnie Smith 19 Jul 1972, Wed Rocky Mount Telegram (Rocky Mount, North Carolina) Newspapers.com