The Morning Call Allentown, Pennsylvania Monday, July 17, 1972 - Page 5

Fischer Holds Edge in 3rd Chess Game

Reykjavik, Iceland (AP) — The third game of the world chess championship adjourned Sunday night after 5 hours and 18 minutes of play with challenger Bobby Fischer apparently holding the edge.

The Rev. William Lombardy, Fischer's second and an American grandmaster, said Soviet titleholder Boris Spassky was “in a bad position. He a pawn down.”

Spassky had five pawns at adjournment, Fischer six. Each retained a queen and a bishop in addition to his king. The game will be resumed Monday.

The American challenger never has beaten Spassky. Before this match he had lost three games to the Russian playing back and drawn two when he played white and had the first move. He lost the opening game of the championship playing black ([due to disruptive men operating the cameras]), as he is in the third game.

Fischer forfeited the second game by failing to appear ([due to boycotting the match in protest of the disruptive men operating the cameras]), and Spassky leads the match 2-0.

Chief Referee Lothar Schmid of West Germany stopped play after Spassky had made his 41st move and Fischer had handed in his reply move in a sealed envelope.

The game was played in an upstairs room. No spectators were present. ([The Rev. William Lombardy, Fischer's second, discounted rumors that the American chess master was flying home. “I haven't heard anything about that and I hope it's not true,” Father Lombardy said. “Everything is still up in the air. We have settled nothing so far.” - Saturday, July 15, 1972])

The adjournment prompted a burst of noise from the hundreds watching the game on television screens in the public auditorium and halls.

“It's great. It's fantastic,” gasped an American student. “I love it. It can't end.”

The game opened with a typical Fischer defense, the Nimzo-Indian merging into the Benoni counter—a strong play for domination of the center of the board, where most kills are made and most games won.

The boy from Brooklyn attacked from all sides: He slammed down the queenside, he switched to the kingside, he switched back to the queenside and then he struck down the middle.

Spassky bit his nails. Fischer leaned back, swiveled in his chair, leaned forward—and moved rook to king two.

It was the 23rd move.

Spassky, moving his 24th, moved queen to queen three. In other words, he mounted his defense.

Spassky's attack was effectively over. From then on he defended, moving slowly.

Fischer moved rapidly. He had the key square of the board—king five—covered with a full four pieces. Spassky had no chance of pushing forward his vital king's pawn to convert. For three moves he shuffled one rook up and down, reduced to utter passivity.

Then, for one moment, it looked as if he had the chance of mate. But Fischer moved one piece, and at once regained the initiative.

That was the 35th move. Six moves later, it was over for the day.

Visiting grandmasters rattled a dozen possible routes to mate off the tops of their heads. Lesser talents worked it out on chess boards.

Spassky arrived shortly before the scheduled starting time for the game—5 p.m., or 1 p.m. EDT. Fischer arrived after the Russian had made his first move, bent over the table with a smile and shook Spassky's hand.

Spassky began the game with a queen's pawn opening, his favorite.

Fischer replied with knight to king's bishop three.

Spassky continued by advancing his queen's bishop's pawn to the fourth rank and Fischer made pawn to king's three.

After Spassky's third move—knight to king's bishop three—Fischer made pawn to queen's bishop four.

The game was beginning along the lines of an opening called the Nimzo-Indian, the line of play in their first game, when Spassky was also playing white. Spassky won that game.

As a silent movie, the several hundred spectators in the 2,500-seat sports palace watched Fischer gesticulate to the referee. There was no sound from the back room.

The referee disappeared from the screen. Fischer fidgeted. He pivoted on his swivel chair, covered his face with his hands, then one by one straightened the 16 black chess men before him, starting with his king's rook. The audience laughed out loud.

After a few minutes, Schmid came onto the empty stage and said he felt obliged to “explain a strange situation.”

“There is a match for the world championship, but there are no chess players here,” Schmid said—meaning in the outer room. “Bobby Fischer protested against certain conditions. He feels disturbed for several reasons.”

The referee said that according to Rule 21 the organizers guarantee players against disturbance. If one complains, he can demand that the game be moved to a closed room.

“I took the responsibility to move the game just for today,” Schmid said. “I made the decision just to save the match.” ([That's a lot of pontificating when after all, it was Schmid leading the Soviet choir in the false claim the cameras CAN NOT be removed, as “Under agreed rules of the match, [Fischer] had the right to object and to demand removal of the cameras if they disturbed him.” -Ed Edmondson, US Chess Federation, who helped draft the Amsterdam Agreement. So why didn't Schmid, simply follow the rules?])

Above the empty stage burned 90 specially installed fluorescent bulbs of mixed colors. Their light was being filtered through 105 specially made frosted glass panels. The intensity of the light could be raised or lowered by a system of switches.

It was installed on Fischer's demand and it cost $5,500. ([Astounding claim require astounding evidence … and this is the first time such a thing has ever been mentioned among the many syndicated press releases, which may be so, or, as often is the case, may not. ★])

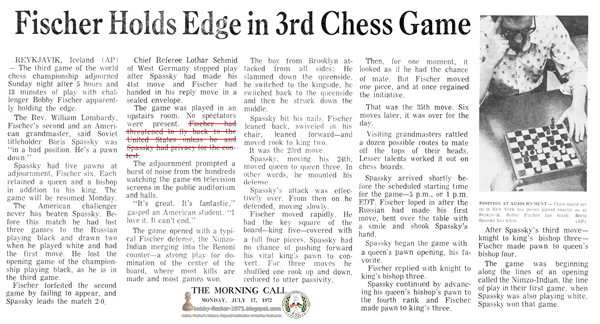

CAPTION: POSITION AT ADJOURNMENT—Chess board set up in New York has pieces placed exactly as at Reykjavik. Bobby Fischer has black; Boris Spassky has white. (AP)