The Sydney Morning Herald Sydney, New South Wales, Australia Saturday, July 01, 1972 - Page 7

Bobby Fischer at the Summit by Al Horowitz

The author of this article has been playing chess for 59 years, since he was six years old. He was a member of the US world chess championship team in 1931, 1935 and 1937, and was a US open champion three times. From 1933 to 1969 he was editor and publisher of “Chess Review.” He is at present chess editor of “The New York Times.”

(CAPTION: Bobby Fischer looks up from a lapful of chess magazines to answer an interviewer.)

Bobby Fischer at the Summit 01 Jul 1972, Sat The Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney, New South Wales, Australia) Newspapers.com

Bobby Fischer at the Summit 01 Jul 1972, Sat The Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney, New South Wales, Australia) Newspapers.com

When Robert Fischer, many times United States chess champion, sits down to play the first game of his world championship match against titleholder Boris Spassky, of the Soviet Union, in Reykjavik, Iceland, on Monday, it will be the first time in 71 years that an American has participated in a face-to-face match for the highest title.

No American has faced a reigning world champion in a direct confrontation for the title since Frank J. Marshall suffered a humiliating defeat by Emmanuel Lasker in 1901.

Those 71 years represent a long period of hope and frustration for American chess fans; and it is little wonder that, now, when a fellow countryman is to play for the title, and is regarded a heavy favourite as well, they should await the event in a fever of enthusiasm.

Many American chess players have followed Fischer's career from the time when, at the age of 12, he first proved himself a force to be reckoned with. When two years later, in 1956, he won the US championship for the first time, there were many who predicted that he would win the world title before he was old enough to vote.

But although he went on to become, at 15, the youngest grandmaster in the history of the game, the road to the summit proved to be much longer and rockier than his admirers had expected.

That road has now led to, of all improbable places, Reykjavik, where play, barring accidents, will begin early Monday morning, Sydney time. The first player to score 12½ points (counting one point for a win, half-a-point to each for a draw) within the limit of 24 games will win. If the match is tied at the end of 24 games the champion will retain his title.

Spassky was also a world championship contender while still in his teens, but, like Fischer, he suffered some sobering setbacks before finally achieving his goal. He should now be at the height of his career, and in ordinary circumstances might be expected to hold on to his crown for many years to come.

However, it is the firm opinion, not only of most American experts, but of knowledgeable people all over the world, that the world champion is a decided underdog.

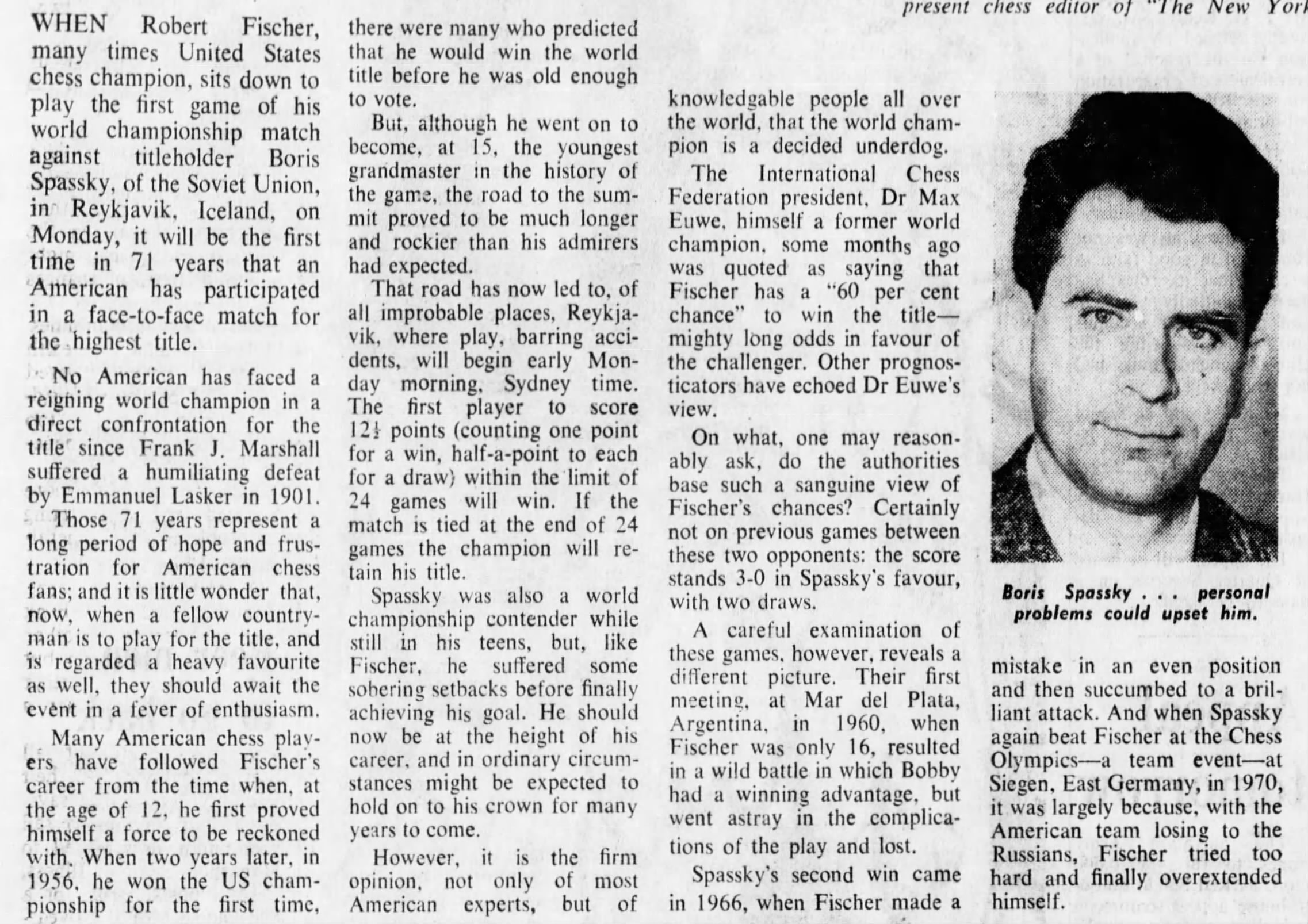

The International Chess Federation president, Dr. Max Euwe, himself a former world champion, some months ago was quoted as saying that Fischer has a “60 per cent chance” to win the title—mighty long odds in favor of the challenger. Other prognosticators have echoed Dr. Euwe's view.

On what, one may reasonably ask, do the authorities base such an sanguine view of Fischer's chances? Certainly not on previous games between these two opponents: the score stands 3-0 in Spassky's favor, with two draws.

A careful examination of these games, however, reveals a different picture. Their first meeting, at Mar del Plata, Argentina, in 1960, when Fischer was only 16, resulted in a wild battle in which Bobby had a winning advantage, but went astray in the complications of the play and lost.

Spassky's second win came in 1966, when Fischer made a mistake in an even position and then succumbed to a brilliant attack. And when Spassky again beat Fischer at the Chess Olympics—a team event—at Siegen, East Germany, in 1970, it was largely because, with the American team losing to the Russians, Fischer tried too hard and finally overextended himself.

Bobby Fischer at the Summit 01 Jul 1972, Sat The Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney, New South Wales, Australia) Newspapers.com

Bobby Fischer at the Summit 01 Jul 1972, Sat The Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney, New South Wales, Australia) Newspapers.com

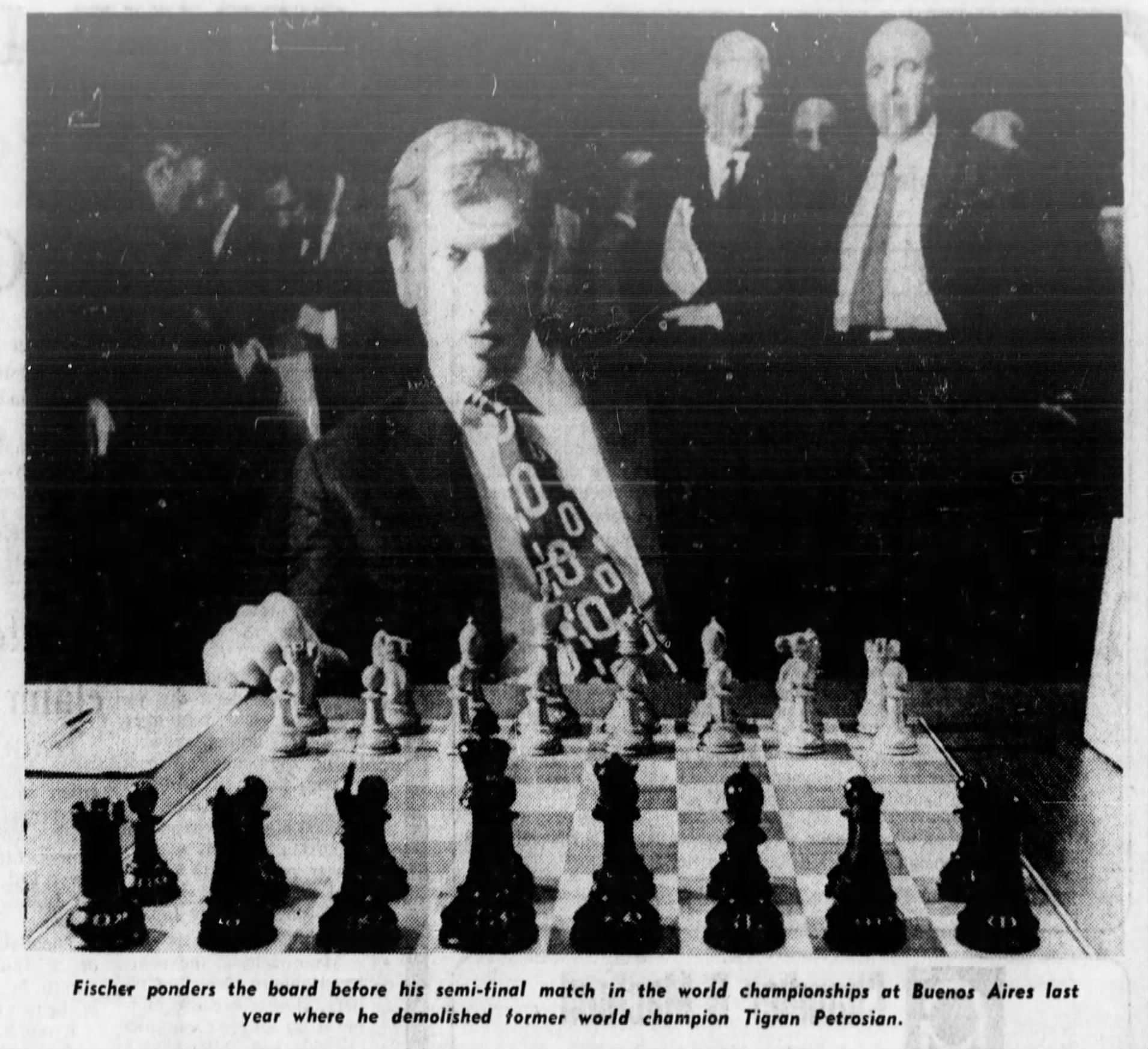

Fischer ponders the board before his semi-final match in the world championships at Buenos Aires last year where he demolished former world champion Tigran Petrosian.

Fischer Ponders the Board 01 Jul 1972, Sat The Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney, New South Wales, Australia) Newspapers.com

Fischer Ponders the Board 01 Jul 1972, Sat The Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney, New South Wales, Australia) Newspapers.com

Surely Spassky's three wins against Fischer without a loss cannot be simply dismissed with a few glib explanations, but close analysis does indicate that their meetings have not been one-sided.

What the experts are basing their opinions on, and rightly so, are the performances of the two protagonists over the past few years. There Fischer has a big edge.

In order to win the right to contend for the championship, Fischer had to win a series of candidates matches against some of the strongest players in the world, and he did so in extraordinary fashion.

First he defeated the Russian grandmaster Mark Taimanov, in a match held in Vancouver, Canada, last May, by an incredible 6-0; unprecedented in this form of competition. Then, in August, at Denver, Colorado, he defeated Bent Larsen of Denmark, widely thought to be the top player of the Western world (after Fischer of course), by the same margin.

And then, to top it off, he disposed of the former world champion Petrosian in a match player last November in Buenos Aires, by 6½-2½.

Meanwhile, Spassky, since winning the title, has had a series of indifferent results. His most recent appearance in a major event was in a tournament in Moscow late last year, when he tied for sixth place—by no means disgraceful in such strong company, but pallid by comparison with Fischer's feats.

Indicative of a player's recent results is the numerical ranking system devised by Professor Arpad Elo, of Marquette University, long used in the US and recently adopted by the International Chess Federation. This system employs a complicated formula to translate tournament and match performances into a four-digit number, and can be employed to predict future results as well.

Spassky's rating is a healthy 2,690 — anything over 2,500 indicates play at the grandmaster level. Fischer's, however, is 2,824 — by far the highest achieved — and enough to make the soberest statician stand up and dance a jig.

Thus, the mathematical projections indicate that Fischer will have an easy time of it, and suggest that the final score will be about 12½-8½ in his favor. This is another way to express Dr. Euwe's opinion—arrived at presumably by intuition—that Fischer has approximately a 6-4 edge.

Chess matches, of course, are not won by reference to probability tables, but over the board.

Fischer is Spassky's superior both technically — his play exhibits fewer weak spots — and temperamentally — Spassky has been having personal troubles recently that have markedly affected his concentration, whereas Fischer's whole life is devoted to chess.

With the qualification that a player who has once won the world championship is of course capable of beating anyone, anytime, the conclusion is inevitable: Fischer will win, and most likely win big.

Fischer is capable of every type of chess—modern, hypermodern and eclectic. In these branches, control of the center is paramount, although hypermodern chess, paradoxically, cedes the center to the antagonist.

All grandmasters agree that it is important to gain control of the center, yet the hypermodernist actually inveigles his opponent into taking control of this area. Why?

In the beginning, plans of this player are long-termed. And, he cedes and bequeaths the center. As play progresses, the hypermodernist's efforts are to retrieve the median area, and every effort is bent on its repossession.

Once regained, the hypermodernist intends to hold on and never to part with it. It goes without saying that the more knowledgeable a player, the great his choice and also the great technician, the finer the play. These are Fischer's attributes. He is confident—and confidence wins games.

Allied with the will to win, it sparks the mental ignition, brings forth ideas, dispels doubts, promotes clear thinking. In contrast, timidity befuddles, inhibits and defeats itself.

Be that as it may, someone suggested to Bobby that the odds ought to be three to one in his favor.

“What?” said Bobby, “the odds ought to be 20 to one.”

Bobby Fischer at the Summit 01 Jul 1972, Sat The Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney, New South Wales, Australia) Newspapers.com

Bobby Fischer at the Summit 01 Jul 1972, Sat The Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney, New South Wales, Australia) Newspapers.com