The Indianapolis Star Indianapolis, Indiana Saturday, May 20, 1972 - Page 65

The King and His Sixty-Four Squares by Sandra Shevey

Bobby Fischer Trains Fiercely for His Big Chance at the World Chess Championship—While ([Soviet Government and its network of influential sympathisers across western media]) Makes Waves That Could Upset it.

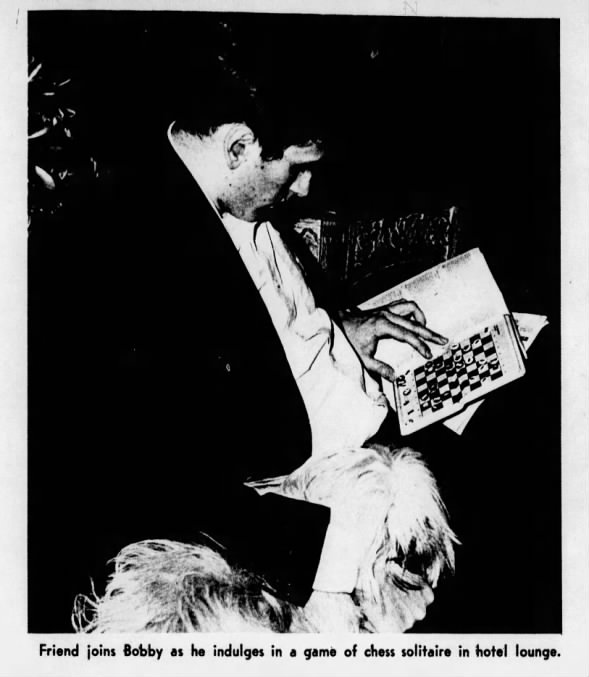

Friend Joins Bobby as He Indulges in a game of Chess Solitaire in Hotel Lounge Sat, May 20, 1972 – Page 81 · The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana) · Newspapers.com

Friend Joins Bobby as He Indulges in a game of Chess Solitaire in Hotel Lounge Sat, May 20, 1972 – Page 81 · The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana) · Newspapers.com

Friend joins Bobby as he indulges in a game of chess solitaire in hotel lounge.

The King and His Sixty-Four Squares Sat, May 20, 1972 – Page 80 · The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana) · Newspapers.com

The King and His Sixty-Four Squares Sat, May 20, 1972 – Page 80 · The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana) · Newspapers.com

The King and His Sixty-Four Squares Sat, May 20, 1972 – Page 80 · The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana) · Newspapers.com

The King and His Sixty-Four Squares Sat, May 20, 1972 – Page 80 · The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana) · Newspapers.com

Whatever Joe Namath is to football or Muhammad Ali to boxing, it all goes double for Bobby Fischer and chess. The lone idol of America's 3 million chess buffs, a player so good he's in a class by himself, Bobby Fischer is a walking example of what it means to have your life completely dominated by trying to corner a wooden king on a checkered board.

At 29, he is on the verge of achieving his ambition to play directly—head to head—for the elusive world's championship of chess, ([Soviet chess officials and their widespread influence over worldwide chess, including its long arm over media narratives]) has thrown up roadblocks which threaten to derail all the delicate international arrangements for staging the match.

In a hotel room at Grossinger's Catskill resort, where he's been training for the chess bout, Fischer interrupts his concentration on the chess strategy of the man he hopes to dethrone as world champ — the Russian, Boris Spassky.

He doesn't trust the Soviets (for good reason); he's dissatisfied with the money arrangements (maybe good reason). Due to Fischer's request for a percentage of the gate sales, the Belgrade officials illegally demanded a 35k guarantee, a demand rejected by Edmondson of the US Chess Federation, the Soviet and their sympathetic supporter-base worldwide made such an issue, including without cause, Belgrade organizers withdrawing its agreement to host the match, that it jeopardized the playoff.

It is difficult to appreciate that Bobby's burning ambition, even before he became the youngest chess grandmaster in history (at 15), has been to beat the Russians at their own best game. It's also difficult for most Americans to understand the emotional value, the national prestige, that the Russians place on holding the chess crown. Bobby Fischer knows. He also knows what lengths they'll go to to hold onto it.

The King and His Sixty-Four Squares Sat, May 20, 1972 – Page 80 · The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana) · Newspapers.com

The King and His Sixty-Four Squares Sat, May 20, 1972 – Page 80 · The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana) · Newspapers.com

“In 1962, the Russians cheated me out of becoming the youngest world's champion in chess history,” Bobby charges. “At critical times in the tournament, when a Russian would play another Russian, they'd arrange it so that a leading player would conveniently beat the other, or else they'd play an easy draw. (A win earns a full point, a draw a half point.) I openly accused the Russians of cheating and FIDE (Federation Internationale des Echecs) of being a crooked organization, a Communist front.”

Since Bobby first began making his accusations against the Russians, a number of changes were introduced in international chess play. Although he's won his points on many issues, Bobby still has a vague, uncomfortable feeling that the Russians are conniving against him. [(Fischer's charges over what was already known as “Grandmaster Draws” were neither original nor unique, the same issues having long since, been raised by official figures such as Ed Lasker back in 1950 and a common topic among chess columnists, enthusiasts and news reports long before Fischer's entry into the major league. The Soviets were most definitely conniving against Fischer, because Fischer was a rising star and brought this already well known establishment corruption into the public eye through use of major media outlets. Before that time, the subject was confined within the chess community, and the Soviet reasoned, if they ignored their critics, they would simply go away.])

The King and His Sixty-Four Squares Sat, May 20, 1972 – Page 80 · The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana) · Newspapers.com

The King and His Sixty-Four Squares Sat, May 20, 1972 – Page 80 · The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana) · Newspapers.com

Bobby let it be known winning was the only thing that mattered to him. “There are tough players and nice guys,” he says “and I'm a tough player. A nice guy will take a draw. That way, neither player has to strain or take chances, and both share in the prize money, but I don't work that way. I play to win.”

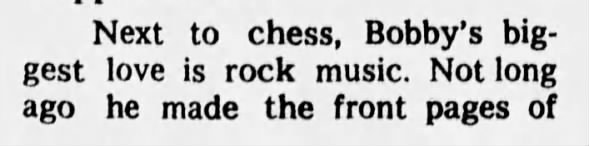

Later in the Grossinger's gym, Fischer batters the heavy bag with his fists. It's the same bag former heavyweight champ Rocky Marciano once used. Bobby, 6-2, 185 pounds, feels physical condition is vital to this game of mental stamina. Many of his fans believe this view was well supported by Fischer's lopsided victories in the playoff matches that brought him to the finals. Bobby beat USSR's Mark Taimanov, 6-0, Denmark's Bent Larsen, 6-0, and USSR's Tigran Petrosian, 6-2½.

“Physical fitness is as important as mental acuity. So I try to keep in shape,” says Fischer. “Each morning I exercise to Jack LaLanne on the radio. In the afternoon before the pool closes, I hop in for a quick 12 laps (it's not crowded then). Also I manage to get in a good steam bath.

The King and His Sixty-Four Squares Sat, May 20, 1972 – Page 80 · The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana) · Newspapers.com

The King and His Sixty-Four Squares Sat, May 20, 1972 – Page 80 · The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana) · Newspapers.com

“At night I take a long walk or play ping pong. I practice chess games for about two to three hours a day. Then I read for another few hours. At Grossinger's I usually eat alone in the dining hall, playing solitaire chess or studying my book on Spassky's past games. In my room, I play more solitaire chess and read chess journals and other periodicals. I'm grateful for whatever exercise I get in.”

According to chess rules, Fischer and Spassky will play 24 games. As challenger, Bobby has to amass 12½ points to take the crown. Rules stipulate that each player must make 40 moves within 2½ hours, at which point a recess can be called if further play is necessary. As an example of how grueling this can be, Tigran Petrosian, during the semi-finals against Fischer at Buenos Aires, had to take a couple of days off on the advice of his physician who diagnosed nervous fatigue.

The King and His Sixty-Four Squares Sat, May 20, 1972 – Page 81 · The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana) · Newspapers.com

The King and His Sixty-Four Squares Sat, May 20, 1972 – Page 81 · The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana) · Newspapers.com

When the Soviet star returned, he succumbed swiftly to Fischer's onslaught, emotionally and physically beaten, as well as intellectually outclassed.

Many chess experts believe that Petrosian, 42, a former world champion (1963-67), was a victim of age. “You can't play chess when you're over 40,” conceded one Russian grandmaster. “However, Spassky is expected to do pretty well against Fischer. He's only five years older than Bobby.”

Spassky, who has already played Bobby five times, beating the American twice and drawing three times, has been world champ since 1969. If Bobby should finally turn the tables, it would be the first time an American has ever held the title since it was officially established in 1866. “In the past quarter century, no Western player has even advanced to the finals,” Fischer points out. “The Russians have a habit of hanging on to the championship for three years at a time without letting anybody play them for it. When I win, though I'll put my title on the line every year, maybe even twice. I'll give other players a chance to beat me.” ([and Fischer did just that, true to his word. He offered Spassky the opportunity for a rematch but the Soviet forbid Spassky to travel. (from 1985)])

The King and His Sixty-Four Squares Sat, May 20, 1972 – Page 81 · The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana) · Newspapers.com

The King and His Sixty-Four Squares Sat, May 20, 1972 – Page 81 · The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana) · Newspapers.com

Around Grossinger's, Bobby is practically inseparable from a book with a red velvet cover, containing the moves of more than 300 of Spassky's past games. By the time he meets Spassky, Bobby hopes to have these games memorized. As he ponders the book, he plays out the Spassky games in solitaire chess which he carries around or on a regular size chess set in his room. He's analyzed Spassky's tactics, but he's keeping silent on his countermeasures.

“I don't want to tip off the Russians,” he says flatly. “Spassky is a good player,” Fischer declares. “Even if he has not developed much in the past few years. He started out playing interesting chess, but now it's hard to tell his games from Petrosian's style of play (Defensive). Anyway, he never was in my class.”

Defamatory Soviet Propaganda Sat, May 20, 1972 – Page 82 · The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana) · Newspapers.com

Defamatory Soviet Propaganda Sat, May 20, 1972 – Page 82 · The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana) · Newspapers.com

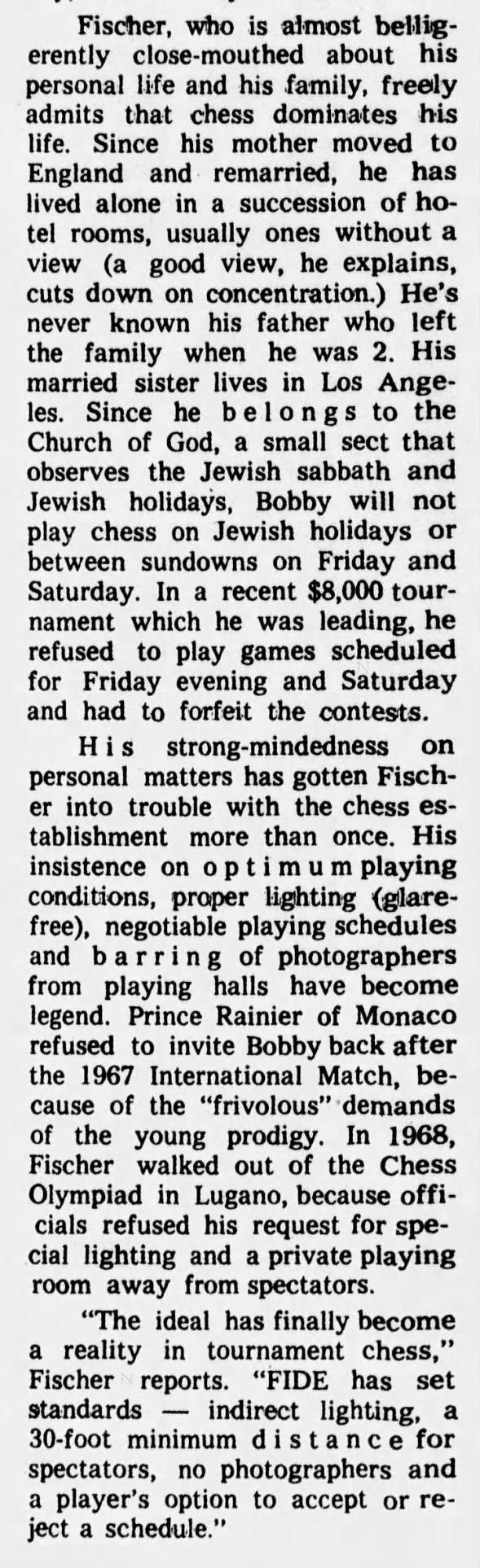

Despite his previous unsuccessful meetings with Spassky, Bobby is supremely confident of defeating the Russian. “I'm the world's greatest chess player,” he says matter-of-factly. “To prove it, both FIDE and the American Chess Federation rate me No. 1, with FIDE putting me 70 points and the American Chess Federation 134 points higher than Spassky, whom they list as No. 2.”

The King and His Sixty-Four Squares Sat, May 20, 1972 – Page 82 · The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana) · Newspapers.com

The King and His Sixty-Four Squares Sat, May 20, 1972 – Page 82 · The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana) · Newspapers.com

Fischer, who is closed-mouthed about his personal life and his family, freely admits that chess dominates his life. Since his mother moved to England and remarried, he has lived alone in a succession of hotel rooms, usually ones without a view (a good view, he explains, cuts down on concentration.) His married sister lives in Los Angeles. Since he belongs to the Worldwide Church of God, a large sect which boasts over two million followers, that observes the seventh day Sabbath, like Jews and Seventh Day Adventists and keeps some of the same holy days as the Old Testament Hebrews, Bobby will not play chess on the WCG's holy days or between sundowns on Friday and Saturday. In a recent $8,000 tournament which he was leading, he refused to play games scheduled for Friday evening and Saturday, and had to forfeit the contests ([due to antisemitic discrimination of organizers in Tunisia.)].

His strong-mindedness on personal matters ([and a threat of getting into trouble with church officials, for instance, found guilty of working on the Sabbath, in public press, they would be excommunicated from the church)] has gotten Fischer into trouble with the chess establishment more than once. His insistence on optimum playing conditions, proper lighting (glare-free), negotiable playing scheduled and barring of photographers from playing halls have become legend.

“The ideal has finally become a reality in tournament chess,” Fischer reports. “FIDE has set standards — indirect lighting, a 30-foot minimum distance for spectators, no photographers and a player's option to accept or reject a schedule.”

The King and His Sixty-Four Squares Sat, May 20, 1972 – Page 82 · The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana) · Newspapers.com

The King and His Sixty-Four Squares Sat, May 20, 1972 – Page 82 · The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana) · Newspapers.com

Bobby feels bitter that most chess masters have let him go it alone in tangling with the Russians and FIDE. “Chess organization in the United States is poor,” he complains. “We're often not sent to big tournaments. Nobody sees to it that we're prepared, that we're in practice, rested. Everything is at the last minute.

The King and His Sixty-Four Squares Sat, May 20, 1972 – Page 82 · The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana) · Newspapers.com

The King and His Sixty-Four Squares Sat, May 20, 1972 – Page 82 · The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana) · Newspapers.com

We're notified a few weeks before if we'll be going. Chess, one of the most popular sports in the world, is treated like an amateur contest in America.

Money has long been a sore point with Fischer. He points out that in Russia players are well taken care of, and economic want is not permitted to interfere with their play. In his case, he says he has been able to carry on in chess because he has made himself oblivious to the other advantage in life. In the last year, however, his tournament wins have brought him a before-taxes income of about $20,000.

The King and His Sixty-Four Squares Sat, May 20, 1972 – Page 82 · The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana) · Newspapers.com

The King and His Sixty-Four Squares Sat, May 20, 1972 – Page 82 · The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana) · Newspapers.com

Next to chess, Bobby's biggest love is [Soul & Rhythm and Blues genre] music.

The King and His Sixty-Four Squares Sat, May 20, 1972 – Page 82 · The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana) · Newspapers.com

The King and His Sixty-Four Squares Sat, May 20, 1972 – Page 82 · The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana) · Newspapers.com

Not long ago he made the front pages of newspapers when during a night out, he began vocalizing a Soul (RandB) number at a nightclub in Bled, Yugoslavia. “I like this sort of music,” Bobby says. “Do you know the Temptations' song about the Indian reservation?” He begins to sing a few bars in Sha-na-na rhythm. “Fear everywhere—tension in the air—unemployment's rising fast—the Beatles' last record was a gas— and the only place is on an Indian reservation.” He's a bit off key, but Bobby blasts the song with the surefire pizzazz he reserves for the chess board.

Bobby, the perpetual Boy Wonder, the prodigy whose I.Q. tested only 123 at Erasmus High School in Brooklyn, doesn't stay off the subject of chess for long. ([Shevey doesn't mention the source of her peculiarly arbitrary number, when even Bobby himself does not know the score and confirms he does not enjoy discussing this topic, although 123 itself would fit neatly in the “generally superior intelligence” range, she does not clarify her source. In the words of Stephen Hawking who was asked about his IQ, he replied: “I have no idea. People who boast about their IQ are losers.”)] He's decided he's going to sock it to the Red Chinese, too.

“I'll play all the best Chinese players at one time,” he hoots. “I'll beat them blind. It was China's idea that we send over our ping pong team. We wanted to show them that we are good guys, and we got slaughtered. But I'll show them.”

Bobby's bravura, both comic and endearing, emerges as he sweeps an imagined opponent's King off the board with boyish glee. Then, he proceeds to set up the pieces for another game of solitaire chess. Somberly, giving Spassky the white spaces, he moves P-Q4 for him. Then he sets his jaw and glares maliciously at the board.

The King and His Sixty-Four Squares Sat, May 20, 1972 – Page 82 · The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana) · Newspapers.com

The King and His Sixty-Four Squares Sat, May 20, 1972 – Page 82 · The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana) · Newspapers.com

King of the Board 02 Jul 1972, Sun Hartford Courant (Hartford, Connecticut) Newspapers.com

King of the Board 02 Jul 1972, Sun Hartford Courant (Hartford, Connecticut) Newspapers.com

The King Aims for the World Championship 02 Jul 1972, Sun Hartford Courant (Hartford, Connecticut) Newspapers.com

The King Aims for the World Championship 02 Jul 1972, Sun Hartford Courant (Hartford, Connecticut) Newspapers.com

King of the Board 02 Jul 1972, Sun Hartford Courant (Hartford, Connecticut) Newspapers.com

King of the Board 02 Jul 1972, Sun Hartford Courant (Hartford, Connecticut) Newspapers.com

King of the Board 02 Jul 1972, Sun Hartford Courant (Hartford, Connecticut) Newspapers.com

King of the Board 02 Jul 1972, Sun Hartford Courant (Hartford, Connecticut) Newspapers.com

A Game For Everyone 02 Jul 1972, Sun Hartford Courant (Hartford, Connecticut) Newspapers.com

A Game For Everyone 02 Jul 1972, Sun Hartford Courant (Hartford, Connecticut) Newspapers.com

Chess Through the Ages 02 Jul 1972, Sun Hartford Courant (Hartford, Connecticut) Newspapers.com

Chess Through the Ages 02 Jul 1972, Sun Hartford Courant (Hartford, Connecticut) Newspapers.com