The Akron Beacon Journal Akron, Ohio Sunday, February 27, 1972 - Page 157

For 15 Centuries People Have Become Chess Nuts

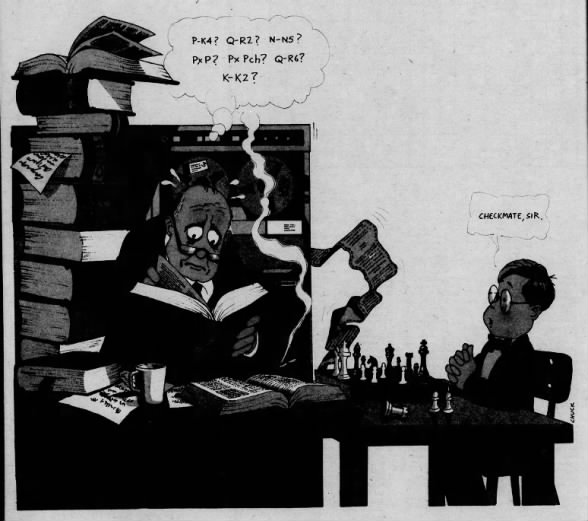

story by Abe Zaidan, cover and inside illustrations by Chuck Ayers

Checkmate, Sir Sun, Feb 27, 1972 – Page 144 · The Akron Beacon Journal (Akron, Ohio) · Newspapers.com

Checkmate, Sir Sun, Feb 27, 1972 – Page 144 · The Akron Beacon Journal (Akron, Ohio) · Newspapers.com

Beacon Sun, Feb 27, 1972 – Page 139 · The Akron Beacon Journal (Akron, Ohio) · Newspapers.com

Beacon Sun, Feb 27, 1972 – Page 139 · The Akron Beacon Journal (Akron, Ohio) · Newspapers.com

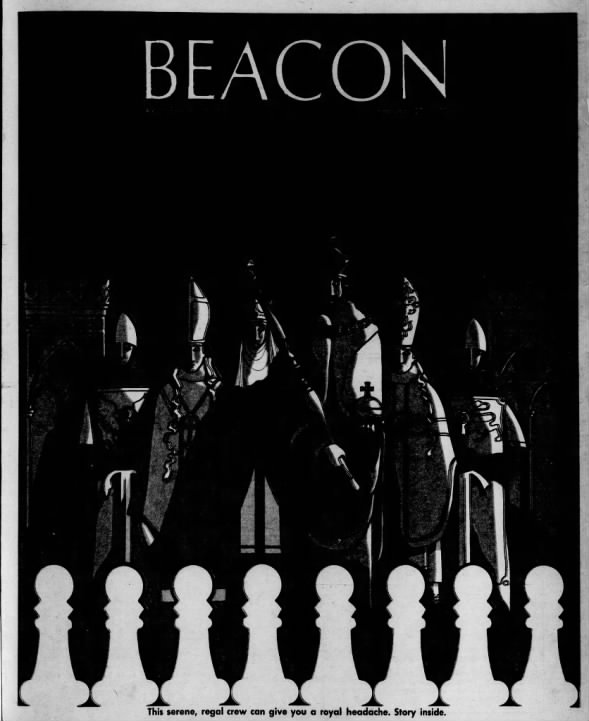

This serence, regal crew can give you a royal headache. Story inside.

Dear Readers Sun, Feb 27, 1972 – Page 140 · The Akron Beacon Journal (Akron, Ohio) · Newspapers.com

Dear Readers Sun, Feb 27, 1972 – Page 140 · The Akron Beacon Journal (Akron, Ohio) · Newspapers.com

Dear Readers…

This issue of Beacon magazine again brings together a couple of very creative people—artist Chuck Ayers and writer Abe Zaidan. Previously, the two have collaborated to produce some fascinating offbeat features for the magazine. Maybe you remember the most recent production, a humorous history by Abe of playing cards, accompanied by some of Chuck's clever drawings. This week, the two focus on the popular game of chess. Chuck's drawing on our cover depicts a chess set any devotee would love to have. For the story and another drawing, see pages 6 and 7.

Chess Nuts Sun, Feb 27, 1972 – Page 145 · The Akron Beacon Journal (Akron, Ohio) · Newspapers.com

Chess Nuts Sun, Feb 27, 1972 – Page 145 · The Akron Beacon Journal (Akron, Ohio) · Newspapers.com

Chess players do things like this: they drum their fingers, fidget and squirm, stroke their beards (real or imaginary), bite through the stems of their pipes, scrutinize their opponents' faces as though they are the maps of Mars, sigh a lot—and stare.

Mostly they stare. At their opponents. At their boards. At clocks. At each chess piece. At nothing.

It is probably the closest modern man will ever come to revisiting the soul of King Solomon.

CHESS is a cerebral process. In place of grocery lists, the day's news headlines, Willie Mays' batting average, credit cards, aching backs, overdue installments, leaky faucets, bus schedules and all the other debris cranked into one's memory bank, chess players transport themselves into loftier, less communicative circles.

They think gibberish like P-K4 (a chess move: pawn moves to the fourth space in the king's file), Q-R2, N-N5, PxP, RxPch, English openings and Sicilian defenses. Sometimes they put an exclamation point after Q-R6 or O-O-O, which means it was a brilliant Q-R6! Or, alas, a disastrous O-O-O!

If none of this makes much sense to the person who has never played chess, it's not supposed to. People who do play chess, if they are honest about it, will confess that they don't always understand it, either.

“CHESS,” according to an Indian proverb, “is a sea in which a gnat may drink and an elephant may bathe.”

That's the beauty of chess. It is so sophisticated in its grand strategies and so vulnerable to muddled thinking that most people can afford to play badly to the grave because they are seldom put to the test of somebody who plays well. There simply aren't that many good players around, which means that bad players have many opportunities to win, and look good when they do.

For all its profundity, chess is believed to have a following of about 60 million players on this earth, and God knows how many on Olympus. At least 60 countries have chess associations. The U.S. Chess Federation reported an 18 pct. increase in membership during a recent three-month period. In 1969, it had 225 affiliated clubs; in 1971, 450.

BUSINESS is booming for the companies that make chess sets, too. Sales are up about 10 pct., and the players are looking for the better-quality sets. Nieman Marcus, the big store in Dallas, says its best seller is a $35 alabaster-type chess set.

The libraries are filled with volumes about chess and you can find out that “moving one square at a time, a bishop may go from K1 to K7 in eight moves in 483 ways.” (The Chess Companion, Irving Chernov.)

Chernov, a chess master himself, also writes that “it takes a knight three moves to check a king that is two away on the same diagonal.

CHESS FANATICS devour this kind of information in the same hungry manner that smart housewives search out the number of ounces in a can of beans. The better chess players even remember some of the things they read.

The books also contain play-by-play accounts, analyses, critiques, rave notices, tsk-tsks and diagrams of the godlier chess matches of history. With the dogged pursuit of Biblical scholars, chess scholars want to know everything about every move in every match and want to record it for the eternal good of humanity.

There, amid those peculiar K-K2's

Continued on page 8

Chess Sun, Feb 27, 1972 – Page 146 · The Akron Beacon Journal (Akron, Ohio) · Newspapers.com

Chess Sun, Feb 27, 1972 – Page 146 · The Akron Beacon Journal (Akron, Ohio) · Newspapers.com

Continued from page 7

and RxRch's, unfolds the intellectual majesty of the masters: Capablanca, Steinitz, Morphy, Alekhine, Tal et al — each with his own epic style, his own grandeur, his own elan. They are alluded to with the same reverence that baseball fans assign to Tinkers, Evers and Chance.

They even earn nicknames that lend themselves nicely to the mystique of the game: Alexander Alekhine, “The Fighter;” Adolf Anderssen, “The Romantic;” Max Euwe, “The Logician;” Jose Raoul Capablanca, “The Machine.”

To be conversant in the exploits of these immortals is to flatter oneself with privileged information. Hence, chess has a snobbery of its own—not all of it justified.

TRUE, the New York Times carries a chess column and the Reader's Digest does not; true, people who think N-N5 or PxP or RxPch are engaged in jargon not unlike those strange sounds our machines occasionally pick up from the universe.

But it also is true that many people who play chess are no more in communion with the deities than a quarterback who fumbles the ball across the goal line for a touchdown. As in anything else, it sometimes helps to be lucky.

Here it is, 15 centuries or so after the game emerged from India or Persia or wherever and there still is no agreement over what chess is—and why.

NOT LONG AGO, Al Horowitz, the veteran New York Times chess columnist, took up the question again. He wrote:

“The safest answer to the old question ‘Is chess an art or a science?’ is the non-committal ‘It's a sport.’ But there are features of chess that link it to the fine arts on the one hand, and sciences on the other, and they can hardly be ignored.”

That recalls what others have decided about chess, including the pungent line that Fred Reinfeld, author of “The Great Chess Masters and Their Games,” attributes to German philosopher-historian Ernst Cassirer: “What chess has in common with science and fine art is its utter uselessness.”

Ah, but what egos it has served, what tempers it has incited, what fools it has exposed, what cowards it has destroyed from the face of the earth!

CHESS IS WAR—reduced to 64 squares, 16 pawns, four rooks, four

Chess Nuts Sun, Feb 27, 1972 – Page 147 · The Akron Beacon Journal (Akron, Ohio) · Newspapers.com

Chess Nuts Sun, Feb 27, 1972 – Page 147 · The Akron Beacon Journal (Akron, Ohio) · Newspapers.com

bishops, four knights, two queens and two kings, divided equally between the two combatants.

The earliest traces of the game suggest an Indian origin in the Sixth or Seventh Century. Chess historians say an Indian philosopher developed the game to symbolize the warring of two Indian armies and named it &lduqo;chaturanga,” Sanskrit for “the army game.”

The pawns were the foot-soldiers; the rooks, chariots; the knights, horsemen; the bishops, elephants (the evolution here is a little harder to follow); the queen, minister; the king, king.

The object of chess today, as it was then, is to annihilate the king by destroying his army.

SOME RELIGIONS denounced chess. Caliphs, of course, loved it. “There is nothing wrong in it,” one ancient caliph is said to have enthused. &lduqo;It has to do with war.”

The early history of chess abounds with tales of how those 64 squares shaped men's lives. Military battles were lost while generals dallied in their war rooms fussing over RxB or QxPch. Lustful noblemen moved their chessboards to the ladies' boudoirs, where their ploys were forever lost to history. Stricken by the call of the board, men gave up promising careers as lawyers and businessmen to dedicate themselves to a monastic existence amid pawns, knights and bishops.

Those who thirsted for even more stylish military victories (“You cannot play at chess if you are kind-hearted,” says a French proverb) learned to play blindfolded; one hot-shot is said to have taken on 45 opponents at once, playing from memory.

IN SWEDEN, in the late 19th Century, they played with costumed men as chess pieces on a 4,305 square-foot board. Earlier, an Austrian mechanic, Wolfgang von Kempelen, even resorted to “automated chess”—devising a mechanical man who sat at the board and responded to each move by a live player. It was a trick, but fully complimentary of the many deceits of chess strategy: Wolfgang had stationed a skillful player inside the automaton and he was eventually exposed.

The scheme, brilliant though it was, was checkmated.

Perhaps the biggest news in chessdom today, at least in America, is that the game is grabbing headlines in the popular media because the Republic

Continued on page 19

Chess Sun, Feb 27, 1972 – Page 157 · The Akron Beacon Journal (Akron, Ohio) · Newspapers.com

Chess Sun, Feb 27, 1972 – Page 157 · The Akron Beacon Journal (Akron, Ohio) · Newspapers.com

Continued from page 9

may be on the verge of claiming its first world chess crown.

THIS SPRING, Bobby Fischer, 29-year-old U.S. national champ who came up from the ranks of a chess whiz kid, will engaged Soviet world title-holder Boris Spassky in what promises to be an historic summit meeting.

The vanities of the players would be enough to qualify the match for Homeric prose, and a spread in Life magazine. But the vanities of two old rivals—the U.S. and the U.S.S.R.—could swell the contest into a showdown in the UN's Security Council.

Fischer is expected to win. Last October he smashed—that's a typical chess verb—former Soviet world champion Tigran Petrosian in Buenos Aires. He is now said to be ready to annihilate Spassky, and thus strip the Soviets of the crown they've held for more than two decades.

“Few,” says the New York Times, “will contest his (Fischer's) rank as the greatest living chess player. Some authorities soberly rank him as the greatest who ever lived.”

FISCHER probably represents as well as anybody the soaring genius and lifestyle of the chess masters. When he wasn't playing well against Petrosian in Buenos Aires, he sulked about his cold, his hotel, his food, the playing conditions. He said he wouldn't play in Russia and fretted about how the Russians would harass him. He suggested the Russians were “plotting” against him.

The Soviets, in return, hissed that Fischer was a “loudmouth, a conceited braggart,” etc., etc., etc.

Fischer is a loner, a hermit, detached from all potential distractions from his beloved chessboard.

“Bobby has no home and no permanent address,” the Times says of him. “He lives out of hotel rooms, and the rooms he picks do not have a view. A view, he says, detracts from his concentration.”

It is hard for some people to understand these self-imposed Spartan disciplines for a mere game that you give for a Christmas present when you don't know what else to buy. But there is very little that mortals are expected to understand when the gods start scrapping among themselves.(End)